The truths of the war in Afghanistan : does visibility decrease support?

On Monday, Wikileaks, a website devoted to exposing the underbelly of the political and corporate world, revealed thousands of documents that, in a nutshell, depict the complications, perils and pitfalls of the war in Afghanistan. One piece of alarming information is that terrorist organizations in Afghanistan are clearly being supported by Pakistan. Another is solid evidence of the corruption of Hamid Karzai (though this has been suspected for quite some time). The force with which this story hit the news this week, the amount of coverage it has received and the combination of this story with recent exposés on the experience of war in Afghanistan and Iraq have created a situation in which increasing amounts of negative press about the war, whether in small leaks or larger bursts, are emerging. The dominant discourse or narratives about the Afghan war – hunting down a terrorist, bringing justice to terrorists in general, rooting out potential terrorist cells or the humanitarian notion that we’re providing a more stable government and safer society for Afghans – feel as though they are shifting. There is increasing discourse about a lost battle, a waste of precious American dollars and young lives, etc. Perhaps this shift is due to the number of soldiers dying, which makes it increasingly likely that you or someone you know or at the very least a distant

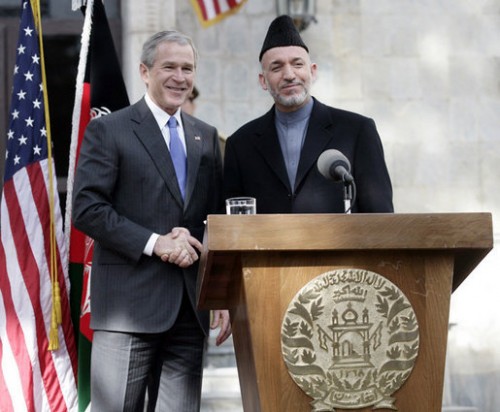

On Monday, Wikileaks, a website devoted to exposing the underbelly of the political and corporate world, revealed thousands of documents that, in a nutshell, depict the complications, perils and pitfalls of the war in Afghanistan. One piece of alarming information is that terrorist organizations in Afghanistan are clearly being supported by Pakistan. Another is solid evidence of the corruption of Hamid Karzai (though this has been suspected for quite some time). The force with which this story hit the news this week, the amount of coverage it has received and the combination of this story with recent exposés on the experience of war in Afghanistan and Iraq have created a situation in which increasing amounts of negative press about the war, whether in small leaks or larger bursts, are emerging. The dominant discourse or narratives about the Afghan war – hunting down a terrorist, bringing justice to terrorists in general, rooting out potential terrorist cells or the humanitarian notion that we’re providing a more stable government and safer society for Afghans – feel as though they are shifting. There is increasing discourse about a lost battle, a waste of precious American dollars and young lives, etc. Perhaps this shift is due to the number of soldiers dying, which makes it increasingly likely that you or someone you know or at the very least a distant  acquaintance is fighting in the middle east. Perhaps it’s our disastrous economy and the potential double-dip recession looming that’s making it harder to justify spending billions to fight a war when about 1 in 10 of us are unemployed at home. It could be any combination of these and/or other factors, but I would like to suggest that the increased access to images, information and general visibility of this war will be a key factor in its demise.

acquaintance is fighting in the middle east. Perhaps it’s our disastrous economy and the potential double-dip recession looming that’s making it harder to justify spending billions to fight a war when about 1 in 10 of us are unemployed at home. It could be any combination of these and/or other factors, but I would like to suggest that the increased access to images, information and general visibility of this war will be a key factor in its demise.

Theories of cognitive dissonance suggest that when our behavior clashes with our cognition, an uncomfortable psychological state ensues. For instance, if I am a pacifist, but engage in a violent act, I will experience distress. As I watch the coverage of the war in Afghanistan since the Wikileaks report was released yesterday, I am lead to think about the role of cognitive dissonance in producing social change. No matter what you believe has happened in Afghanistan, the narrative of success and progress, whether in the realm of hunting down terrorists or establishing better government, is at odds with the information in the Wikileaks documents that depict chaos. Changes in attitudes about the Afghan war have been brewing for months. Will this new and increasingly prominent information about the problems of “winning” this battle create psychological tension for many Americans who previously supported the war?

Another key piece to dissonance theory is about action – dissonance motivates a change. We must resolve the tension between our cognition and our behavior. According to classic theories, we are driven to do so in the same way as we are to satisfy thirst or hunger. For most Americans, the reality of war is a distant thought. Most of our immediate and even extended family members are not fighting abroad. Thus, support for the war may not be challenged on a daily basis because we’re simply not faced with the relevance of the situation. For instance, my grandfather was a WWII vet, my step-father fought in Vietnam and yet, for me, war in general is something fought on other continents, far far away from my reality. If I were to support the war in Afghanistan, it would be easy to avoid competing knowledge – if I were not an avid news consumer, etc. It is for that reason that accurate media coverage, transparency of governmental action and an informed public are so vital to ending wars. Not only does the access to images and information about the war increase cognitive tension, but it bring the experience closer to home. After all, the draft is ultimately what led to the end of the Vietnam War — quite simply, we’re more likely to be called to action to protest something if it affects us personally. The combination of dissonance and relevance could certainly be the key to ending this war.

Most people can agree that war is bad, it is brutal, it is horrific and it is a drain on resources we desperately need to strengthen our crumbling institutions in America. It also exposes hundreds of thousands of young men and women to violence and terror that has lasting consequences for their physical and emotional well-being. Perhaps some cognitive dissonance is not so bad, especially if the reality of what’s going on abroad is even more dire than we’ve been lead to believe. It remains to be seen if visibility, dissonance and relevance will lead to increased discontent with this war.