The Soda Ban and Sociology

found at http://www.sodahead.com/living/new-york-city-may-ban-sodas-larger-than-16-ounces-smart-or-stupid/question-2693881

In the past few weeks, New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has made national headlines with his proposal to ban large sized sodas at restaurants, theaters, stadiums, delicatessens and food carts. The proposal aims to encourage people to drink less of the obesity-causing sugary drinks.

The immediate reaction in the media was not kind. Those on the political right attacked the ban as an assault on personal freedom. Even those associated with the left, like comedian Jon Stewart lambasted the proposal. A full page NY Times advertisement featuring Mayor Bloomberg in a dress was entitled, “The Nanny: You only thought you lived in the land of the free.” These criticisms are not, in my view, simply part of an ideological battle about the proper role of government but also part of a disagreement over the validity of the sociological imagination.

Of course, there are valid questions about the proposal. For example, would reducing cup sizes lead to lower soda consumption? How much impact does soda have on obesity? These are empirically verifiable and scientific questions, but the notion that the cup size ban is an assault on freedom relies on an anti-sociological understanding of society.

The assertion that choice is being taken away by the government assumes that either cup sizes result from free and unencumbered choice in the marketplace or government control. Choices, however, are not unencumbered in the absence of government dictates but instead, conditioned by an array of social factors.

People make choices within social contexts not entirely of their own construction. Without this basic tenet of sociology, social norms and social structures would be irrelevant. Every social phenomenon from crime to politeness would be explained as follows: crime exists because people choose to commit crime and politeness exists because people choose to be polite. If these assertions were all we needed to know about society, PhD programs in Sociology wouldn’t exist. But, since an individualistic analysis of social life is both overly simplistic, and often tautological, our society needs a sociological imagination and the social research that academic sociology produces.

With regard to obesity, the assertion that someone should be free to choose obesity-causing products suggests that individual choices caused rising obesity rates. The notion has broad appeal as obesity, like other social ills, is often viewed as a moral failing.

The non-random distribution of obesity across time and place requires a social rather than individual explanation. Research confirms that social contexts condition obesity rates. A series of social factors and institutions like advertising rules, food labeling, the FDA, nutritional guidelines, school lunches, the farm bill and various agricultural policies and even trade policies substantially alter our food environment. The question is not whether our food environment is managed, the question is whether profit-seeking companies manage it or a democratically elected government manages it. Dealing with obesity and ignoring the social context will likely lead back to the moralizing and victim-blaming that distorts so many other social problems in our society.

People often take offense to societal explanations for what they deem personal behavior. Sociologists, therefore, must be clear that we are not saying that living in an area with unhealthy food will make someone obese. Or conversely, that everyone who lives in a healthy food environment will be at their ideal weight. Diet is conditioned by but not determined by a set of social factors.

Perhaps a sizable portion of the public understands that individual diets and social conditions are related. The public reaction to the cup size ban was actually not as negative as I was led to believe by news headlines. Instead, a slim majority 51-46 opposes the ban. Women narrowly support the ban 50-47. The poll also asked questions like whether the government should be involved in people’s eating and drinking habits (46 percent say yes). Conversely, I wonder how many respondents believe that large institutions (e.g. major corporations, government) can be neutral with regard to eating and drinking habits. I also wonder whether or not the libertarian beliefs that underlies much of the “freedom” discourse in contemporary America are anti-sociological? Or put another way, is the sociological imagination a political position in contemporary society? Is the excerpt from C. Wright Mills’s The Sociological Imagination that so many Intro to Sociology courses assign a political statement?

Further Reading:

Lee, Hedwig – Inequality as an Explanation for Obesity in the United States

New York Plans to Ban Sale of Big Sizes of Sugary Drinks – New York Times

Persistent Obesity Fuels Soda Ban by Bloomberg – New York Times

The premise that social forces underlie the growth in American obesity does not lead to the conclusion that it is the job of the state to intervene and prohibit consumption. The argument is a non sequitur. Remember, very similar logic was use to curtail alcohol consumption during prohibition. Drunkenness and male desertion is caused by social forces. Ergo, we must take steps to outlaw people from drinking it. Non sequitur. Banning beverages must rely on other assumptions.

Here is the problem: obesity is a multi-faceted proble. A soda ban will surely have some impact on calories consumed, but it is not a sufficient fix. Uf we really are serious about addressing obesity, we will also need to mandate exercise, stamp out fast food restaurants, and forbid street vendors from selling ice cream too. Is the state willing to take those steps? If such legislation was capable of reducing obesity, would the ends justify the means? Political philosophy in the liberal tradition pushes back and says that even if we could mastermind a set of interventions that mitigated prevailing social forces by eliminating individual behavior, it would be unethical.

In conclusion, it is possible to have a “sociological imagination”, but also to determine that the state–as a social institution–should have limited jurisdiction over personal behavior. Recognizing that social forces are at work does not provide a prescriptive policy agenda.

Thanks for your thoughtful comment. I’ll try to respond to each of your points. So, in no particular order –here goes.

1.I agree that Prohibition was largely a failure. While it initially led to a decrease in consumption, eventually alcohol use rebounded. In my post, I conceded that a policy intended to curb consumption and change a behavior might fail. This is not my main point, however. I consider the efficacy of a proposal a testable proposition. The costs of testing a cup-size ban, I think you would agree, are far lower than Prohibition. I cannot imagine this ban would enable a crime syndicate.

2.I think you are misreading my larger point – which is perhaps my fault. But, I did not say that since social forces underlie obesity the government must intervene. In fact, I am disputing that very construction of the problem. Government cannot help but intervene in those social forces. Basic government functions like zoning laws, highway construction, mass transit, agricultural policies etc. affect those social forces. Even if government were to abandon all of these functions and reduce itself to the hypothetical “nightwatchman state” the social environment still matters. In other words, power does not revert to personal choices. My argument is against the false dichotomy between personal freedom and government dictates.

3.Obesity as you mentioned is a multi-faceted problem. But altering the social environment is not the elimination of individual behavior (or choices). Let’s take the school day as an example. Right now, physical education time is being cut and, in many places the school day is being increased. The time spent in sedentary activity is increasing for the nation’s youth. We could mandate an increase in physical education but doing so does not take away individual choices because how students spent their school day wasn’t their decision in the first place.

4.When I go to a movie theater or a baseball stadium the current cup choices are not my personal decision now. Only by ignoring the existing social environment could I believe that changing the cup sizes was an assault on my personal freedom.

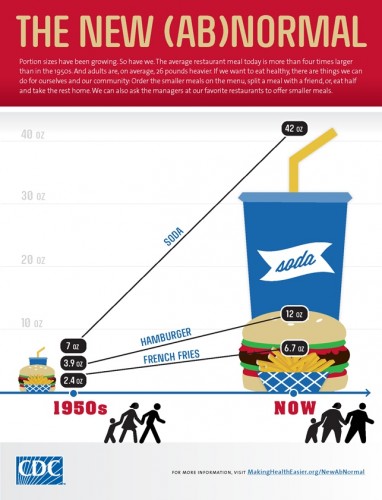

5.The food environment in the United States has radically changed in the last 50 years. Those changes were primarily the result of decisions by government and business not the individuals. That basic point is what I believe is missing when someone claims a new regulation curtails freedom and choice.

6.Finally, changing the food environment is what caused the obesity crisis. While we can certainly disagree about how we should change it now, that environment must change in order to reverse the current trends.