Social Class: Income, Wealth, and Race

Lately there has been a lot of talk about class, and not just the vague election year pandering to the vague demographic of the “middle class.” Instead, the very concept of class has become a subject of debate. Last time, I focused on Mitt Romney’s comment’s about “people who have fallen out of the middle class.” This time I focus on fellow candidate Rick Santorum’s criticism of Romney for using the word class. Here’s what Santorum said:

Lately there has been a lot of talk about class, and not just the vague election year pandering to the vague demographic of the “middle class.” Instead, the very concept of class has become a subject of debate. Last time, I focused on Mitt Romney’s comment’s about “people who have fallen out of the middle class.” This time I focus on fellow candidate Rick Santorum’s criticism of Romney for using the word class. Here’s what Santorum said:

“There are no classes in America. We’re a country that don’t allow for titles. We don’t put people in classes. Maybe middle income people.”

Once again, it’s tempting to dismiss these statements as bizarre gaffes perhaps brought on by a grueling campaign season. However, I have convinced myself that there are no “bad” political soundbytes. Partly because shouting “what are you insane?!?!?” at my computer is apparently frowned upon at my local Starbucks, but also because such comments often provide a useful starting point to discuss a complex phenomenon like class.

As I and most professors tell our students, “there are no stupid questions.” Since there is little benefit in simply telling students they are wrong, we look first at what is accurate or least important about even the most seemingly disconnected question or inaccurate representation of society. I have adopted the same attitude toward “talking points” and “gaffes.” Of course, students are often seeking further explanation, while politicians are not exactly asking for my input. But, my treatment of these statements, rather than their intent, is what I can control. So I will answer Rick Santorum in this fashion.

So, yes, Mr. Santorum, you are correct that if we use something like income quintiles, the people that fall within those boundaries are not exactly in a class as we usually conceptualize it – a group of people with some shared economic situations and corresponding economic interests. Falling within the boundaries of the 2nd and 4th income quintile does not mean that one has the same interests as everyone else within those borders and different or conflicting interests with those in the 1st or 5th quintile. For example, if someone moves from one quintile to the one directly above it their economic interests are unlikely to change. Furthermore, economic interests are not discernible from income only.

First, the kind of income matters. As you may know, the tax rate on unearned income (like capital gains or dividends) is much lower than on earned income from wages. While those with more income likely have a larger share of their income coming from things like capital gains, the correlation is, of course, not perfect. Which leads to a second point: economic interests have a lot to do with economic capital (or wealth accumulated overtime).

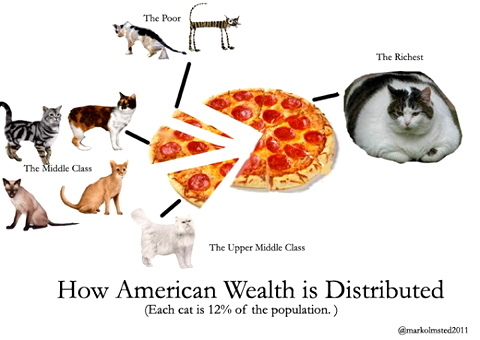

When we avoid assigning fixed “titles” like class based solely on one measure we can address the role of wealth and, for example, consider the enormous racial wealth gap. The median wealth of white households is now 20 times that of black households and 18 times that of Hispanic households. In other words, middle-income whites and middle-income blacks are not similarly situated in our class structure.

We should also keep in mind, as you imply, that social class is not an individual attribute. Instead, as Karl Marx pointed out each economic order creates a class structure. In other words, the meaning and effect of class as well as the very existence of some classes is a result of a social order. Since we don’t assign titles in this country, and since we are a democracy, we have the freedom to alter the class structure and even tinker with the effects of social class without overturning an entire economic order.

For example, the rising costs of college and the corresponding cuts to education and/or abandonment of students to scam (or to be politically correct: “for-profit”) colleges disproportionately impacts the asset poor, who could be middle-income people. However, as racial minorities are disproportionately represented among the asset poor such policies will have a more negative impact on blacks than whites. If, on the other hand, college were fully publically-funded, the wealth gap would be less consequential in terms of educational opportunity. As Mr. Santorum has helpfully pointed out, moving beyond income, we can see that class is complex, but we must be careful not to ignore class simply because we cannot reduce it to a single measure nor employ class to explain all social outcomes.

Conflating Apples and Oranges: Understanding Modern Forms of Racism by W. Carson Byrd

1 Response

[…] Lens: “Social Class: Income, Wealth, and Race,” by Jeff […]