Republican win in Massachusetts – The tipping point for abandoning health care reform?

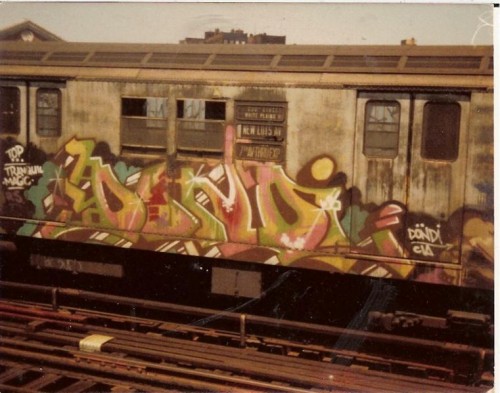

Last week, Senator Edward Kennedy’s long-held senate seat went to a Republican, Scott Brown and marked what will likely be the beginning of the end for the health care reforms – changes that were likely to pass if this incredibly close race had gone to the Democratic candidate. This election, or more accurately, the discourse surrounding the “big Republican win” is, in many ways, the tipping point toward more conservative fiscal and social policy. In The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, Malcolm Gladwell reinforces a principle central to sociology: the environment affects individuals’ behavior, Further, he claims change often happens quickly and in unpredictable ways. In particular, Gladwell shows how little things like graffiti on the subway or broken windows in a neighborhood can actually be the factor that pushes people over the edge into criminal behavior. Likewise, changes to the environment such as clean subway cars and orderly physical structures can prevent crime. In other words, it’s not character or psychology, but the environment that makes the actor act. Similarly, Brown’s campaign, which was particularly focused on blocking health care reform, with slogans indicating just that, and his surprising win of a traditionally democratic senate seat became a visible icon for frustration with the current state of political affairs and possibly with the President himself. This likely will be a watershed moment when the media refrains from the last year of discussion of the death of the Republican party and instead picks up on the undercurrent of frustration and disappointment with the incumbent party, alluding to the possible ousting of the Democratic majority in congress.

Last week, Senator Edward Kennedy’s long-held senate seat went to a Republican, Scott Brown and marked what will likely be the beginning of the end for the health care reforms – changes that were likely to pass if this incredibly close race had gone to the Democratic candidate. This election, or more accurately, the discourse surrounding the “big Republican win” is, in many ways, the tipping point toward more conservative fiscal and social policy. In The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference, Malcolm Gladwell reinforces a principle central to sociology: the environment affects individuals’ behavior, Further, he claims change often happens quickly and in unpredictable ways. In particular, Gladwell shows how little things like graffiti on the subway or broken windows in a neighborhood can actually be the factor that pushes people over the edge into criminal behavior. Likewise, changes to the environment such as clean subway cars and orderly physical structures can prevent crime. In other words, it’s not character or psychology, but the environment that makes the actor act. Similarly, Brown’s campaign, which was particularly focused on blocking health care reform, with slogans indicating just that, and his surprising win of a traditionally democratic senate seat became a visible icon for frustration with the current state of political affairs and possibly with the President himself. This likely will be a watershed moment when the media refrains from the last year of discussion of the death of the Republican party and instead picks up on the undercurrent of frustration and disappointment with the incumbent party, alluding to the possible ousting of the Democratic majority in congress.

My purpose here is not to assess Gladwell’s “broken windows” or “tipping point” theory, but rather to suggest that there are many situations, some much more ephemeral, that call for an examination of the “environmental” or “aesthetic” influences on individuals. In this case, I would like to suggest that, aside from the very real and objective consequences of the loss of Kennedy’s senate seat in  Massachusetts to a Republican – the reality is that the filibuster-proof senate is no longer a stronghold for the Democrats – seems to have had a tipping-point-like effect of this event. Yes, every senate seat is important, but in the grander scheme of things, this is but one of the one hundred seats in congress. However, the message or appearance of this one loss for the Democrats or perhaps this one win for the Republicans is really the damaging element here. Even before Brown won his seat, the pundits launched into predictions that a vote for the republican candidate was a vote against health care and the Democrats more generally. It may also be a vote against the high unemployment rates, but the graffiti, so to speak, in this situation ensconced people in a sense of revolt against health care reform and the conversation this election and Brown’s visible campaign catalyzed is one that is very different than the discussion even one week before this shift in the balance of the senate.

Massachusetts to a Republican – the reality is that the filibuster-proof senate is no longer a stronghold for the Democrats – seems to have had a tipping-point-like effect of this event. Yes, every senate seat is important, but in the grander scheme of things, this is but one of the one hundred seats in congress. However, the message or appearance of this one loss for the Democrats or perhaps this one win for the Republicans is really the damaging element here. Even before Brown won his seat, the pundits launched into predictions that a vote for the republican candidate was a vote against health care and the Democrats more generally. It may also be a vote against the high unemployment rates, but the graffiti, so to speak, in this situation ensconced people in a sense of revolt against health care reform and the conversation this election and Brown’s visible campaign catalyzed is one that is very different than the discussion even one week before this shift in the balance of the senate.

In sum, the feeling that Republicans are on the rebound and that Democrats are in trouble and that health care reform is an impossibility, now, was sparked by this election of Scott Brown in Massachusetts and is much like the graffiti on the subway walls that plagued the MTA in the 80’s (the negative connotation, of course, is felt by the Democrats alone). In other words, aside from the “reality” of what Democrats lost or what Republicans “objectively” gained, what was most important about the election of Brown was the message it sent to Americans and to the rest of congress. This could have been spun as just one election, which, in the grander scheme of things, is not the end of the Democratic party or necessarily the end of any health care reform, but it seems to have become the broken window constantly reminding people of all the ills of revamping the health care system. It has, perhaps, pushed Americans who were on the brink, unsure of which partly to support about reform, to think that Massachusetts citizens are the voice of the nation now.

1540-6237/asset/SSSA_Logo-RGB.jpg?v=1&s=c337bd297fd542da89c4e342754f2e91c5d6302e)

1467-7660/asset/DECH_right.gif?v=1&s=a8dee74c7ae152de95ab4f33ecaa1a00526b2bd2)

1.

Since I’m a fan of Merton, and a pedant besides, I cannot help this opportunity to point out an instance of the Matthew Effect (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matthew_effect). And this stuff is commonly-known enough to just drop Wikipedia links, so that’s handy.

“Broken windows” is not Gladwell’s theory. It’s best attributed to James Q. Wilson, George L. Kelling, and Catherine Coles (see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fixing_Broken_Windows). I’m actually kind of doing Gladwell a favor here, as broken windows has fared pretty poorly in criminological research. So he shouldn’t take too much blame for it.

Gladwell is a social science journalist… or, if he would prefer, a pop social scientist, but that label seems more pejorative to me (maybe not to others). And there are upsides and downsides to his role; he can do an excellent job popularizing social science to a wider audience, but on the other hand, he can obscure thorny details of social science as well as genuine intellectual history (as in the case of, say, broken windows theory…). So someone can end up with a caricature of sociology, or criminology…

I think Steven Pinker, as a genuine social scientist who also writes for a mainstream audience, has a useful take on Gladwell: http://www.nytimes.com/2009/11/15/books/review/Pinker-t.html (But don’t get me wrong; ANYONE is better than Dubner and Levitt.)

2.

Back to the topic at hand. I don’t think the tipping point is a real social event. It is a frame. It’s an analogy (I mean, literally, the use of the phrase “tipping point” is always an analogy). To Republicans/conservatives, this is definitely a tipping point, the date at which the American people struck back against the tyranny socialist fascist communist etc. etc. etc… but that’s a talking point. It’s spin. It’s not based on consideration of the facts, it’s based on political gamesmanship.

You write about the “feeling” of this election and that it “seems to” be a broken window. You suggest that “it” has pushed Americans on the brink…

But that’s not the case! The election has not pushed anyone anywhere; it is an inarticulate social event. The politicians push their framing, as do the media and pundits (so often one and the same, these days). This is all about the interpretation of an event, and you’re missing that.

To draw an analogy back to the broken window hypothesis, this election is as if vocal residents of a community started marching up and down the street screaming “THE WINDOWS IN THAT WAREHOUSE ARE BROKEN! THAT MEANS THE POLICE WILL NOT NOTICE AND NO ONE WILL CARE IF WE STEAL EVERYTHING AND START SELLING DRUGS AND SHOOTING PEOPLE!” They might believe it, and you might believe it, but is that the window’s fault?

First of all, the name of my state is misspelled in the post’s title. Second, there are a plethora of other possible explanations that have and could be advanced for the fact this seat fell to a Republican. Chief among them are social movement analyses focusing on the influx of resources from outside the state and media framing of issues in the campaign. A cursory examination of the turnout by city suggests an analysis might be in order to determine whether it is true that turnout was higher in the wealthy suburbs, and lower in more traditionally Democratic strongholds.

The Coakley campaign did make significant mistakes in underestimating the organization of the Brown campaign. It failed to put boots on the ground, to make appropriate use of its air time, to counter the factual distortions of the Brown campaign, and to make an effective emotional appeal. All of these questions fall squarely within the realm of a movement analysis, and more importantly are local issues. They are not as reflective of the national mood as some would claim. Exit polls have shown that a significant number of Brown voters who were Obama voters support the public option. It’s not the “ills of revamping the health care system” so much as the ills of not going far enough with reform that are at issue here.

The analysis suggested above does not seem to balance structure with agency. It has turned out that the filibuster-proof majority was not necessary to bring health care to fruition after all, because Democratic support for it cannot be counted on precisely because a bill without a public option makes them vulnerable in upcoming contests. Therefore, the loss of the seat here is largely symbolic, and there is agency in framing the loss in ways that overstate its impact. National Republicans were just as stunned as Democrats by this win, and maintained radio silence for a few days, presumably to determine how this could be spun. To see Brown on the evening news, one would think he were still campaigning. Why is that?

Lastly, it’s hard to see how health care could have been the issue for Massachusetts voters except through ignorance of the national proposal or an informed insistence on the public option. This is because Massachusetts already has a plan which resembles the national one, particularly in its adoption of the individual mandate.

Massachusetts citizens may be the voice of the nation, but are we hearing clearly their views on health care and other issues of the day?

I have corrected the error in the post’s title – ed

Thanks!

I appreciate the comments and just want to respond briefly. In this short piece, I’m not claiming that this is the ONLY force at work here – it’s just a suggestion as to one of the possible reasons that the national discussion shifted so rapidly in a short period of time. It’s about this event as an iconic moment.

Rolton, to your second comment – I agree, I do use the language of this tipping point as a real event and I agree again that it’s more about the construction of the event and, as I say, about the spinning of it. Of course, there are real phenomena, but my point here is more about the symbolic. However, the reason I originally thought of Gladwell was precisely because of the relationship between the physical space and action – which are actually both symbolic and real.

To Richard Hudak – You point out some interesting issues, but we’re talking about different elements of the election in many ways. One thing that you seem to misunderstand about my argument is that I’m not claiming that there was a tipping point that led to the election in MA, but rather that the election itself became something that will potentially (and has already) affected the “fate” of health care. In other words, that MA has health care that resembles the proposed national plan, if anything, made it possible for the pundits to say – “see, look, EVEN Massachusetts went to a Republican.” My very brief argument is not so much about what happened before the election, but after. Whether the Coakley campaign didn’t do the best job they could, for instance, is, again, interesting, but a slightly divergent issue. I’m talking about what the election did – not what led up to it, though it is a very important issue in itself.

An interesting poll and story from NPR this morning:

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=122993562

I think you are right that what happened in MA was not precipitated by a tipping point. Residents of this state already have a universal health care policy in place, which includes mandatory purchase of health insurance. Thus, residents of MA might be the least impacted by the outcomes of health care legislation (although it might impact the state’s budget if federal funding foots the bill).

I would add that Malcolm Gladwell did win a public sociology award from the ASA–I think 2 or 3 years ago. So, it is safe to say that sociologists find his work to be worthy of attention.

Thanks for an interesting post–writing from a Coakley stronghold.

Keri