Breadwinning Mothers and the Importance of Intersectional Thinking

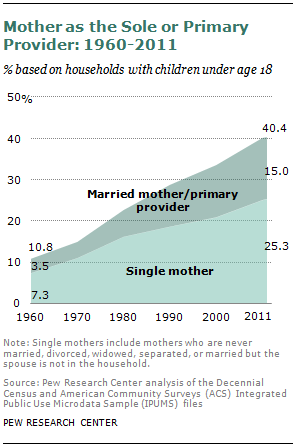

It is hard to imagine that only several decades ago, many women in the United States did not work outside the home. If they did work, their income was a supplement to the household, not the primary share. In fact, in 1960, census reports found that mothers were the primary breadwinner in only 11% of households. A new Pew Research Center study shows us how much times have changed. Not only are women working and making more money than ever before in history, the Pew Center is now reporting that mothers bring in the primary income for 40% of U.S. households. This is a dramatic shift in the politics of gender, work, and family in a relatively short amount of time.

Yet, not all women benefit equally. It turns out that there are two types of breadwinning mothers: married women who out earn their husbands and single mothers who are the only source of income for the family. The married women constitute 37% of the breadwinning mothers. They are well educated, better paid, older, and disproportionately white. The single mothers constitute the majority of breadwinning mothers, or 67%. They are less educated, poorer, younger, and usually women of color.

This report reminds us about the importance of intersectional thinking: while the general numbers provide evidence for women’s greater importance for household finances, a closer look shows us that race and class matter, too. Some women (white, married, educated) have access to better paying jobs, allowing them to out earn their husbands. Other women (women of color, single, less educated) have access to fewer resources and must do it all on their own.

While this report generates a number of avenues for sociological inquiry, I want to turn our attention to a recent Sociology Compass article, “Race and Sex Discrimination in the Employment Process.” The authors, Sheryl Skaggs and Jennifer Bridges, argue that employment discrimination is complex and multi-faceted. Discrimination based on sex and race occurs at all levels of the employment process from hiring to wages to promotions and evaluations of job performance. While organizations have some practices that shield workers from discrimination, there are too many opportunities for individual bias to play out in the employment process. Employers are likely to hold stereotypical ideas about race and gender, including the abilities and productivity of different racial groups and different genders. Ultimately, Skaggs and Bridges call for thinking about workplace discrimination as a set of processes, rather than a static phenomenon.

Skraggs and Bridges introduce some theories that help us understand the complex nature of workplace discrimination; these theories are useful for thinking about the breadwinning mothers data. The first theory, statistical discrimination, explains that many employers will make decisions about hiring, wages, and promotions based on their perception of a worker’s commitment to the company. In the case of the single working mother, employers are likely to think that she is stretched too thin and won’t be a “good value.” The second theory, bias, is simply a theory of racial and gender discrimination; this theory suggest that employers don’t think single women of color mothers are as capable of completing the job and so they are not given as many opportunities at all levels of the employment process.

While I have used the Sociology Compass article by Skraggs and Bridges to explore the new data on breadwinning mothers, there is still much more to be said. What do you think?

Suggested Readings:

Chesley, Noelle. 2011. “Stay-at-Home Fathers and Breadwinning Mothers: Gender, Couple Dynamics, and Social Change.” Gender & Society 25(5): 642-664.

Nakano Glenn, Evelyn. 2004. Unequal Freedom: How Race and Gender Shaped American Citizenship and Labor. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

1530-2415/asset/SPSSI_logo_small.jpg?v=1&s=703d32c0889a30426e5264b94ce9ad387c90c2e0)