‘You can’t see me!’ How our consumption habits are becoming invisible

By PierreSelim (Own work) [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The space between you and the screen is your space. We talk a lot about how we live in a surveillance society, but actually we can now live more secretive and discreet lives than ever. The presentation of the self is far more complicated in a world when we spend significant parts of our time online, not presenting ourselves to anyone much. The websites we visit, the products we buy, the stuff we read, is very much our own business.

We can, of course, leave big clues to all this by sharing and posting stuff on social media, but it appears people are doing this less and less. Last year saw a 9% decline in facebook users, according to GlobalWebIndex (GWI), a research firm that claims to run the largest ongoing study into digital consumption to date.

Many people seem bored of the idea of advertising their every move online. According to the GWI research, around 40% of Facebook users said they had “browsed their newsfeed for updates without posting or commenting on anything” in the last month. We are becoming passive lurkers more than active contributors online. Maybe this reticence is a reaction to the increasing suspicion that our every move online is being monitored by… well, you name it.

Post-Snowden, I wouldn’t be surprised if Google, Facebook, my bank, the companies who made the apps I use, the NSA, ISIS hackers, bored geeks and con-artists, ANYONE, if they were so inclined, could work out my entire life history since about 1998, when I opened my first email account with yahoo. Maybe the knowledge that big brother might be listening is making us say less. Or maybe the novelty of social media is just getting a bit old.

An article in Forbes, citing the GWI research, claims that “Facebook has become more of a passive hub for underlying social connections than a place to actively share our thoughts. And with so many checking Facebook on their smartphones, they’ll often only check in for short periods anyway, leaving little time to do more than browse and maybe “like” a photo or two.”

But to that man sat next to you on the train, or your friends, or even your spouse, most of what we do online is our own business. Maybe we are “being watched by google”, but as long as the people we know are in the dark about our online behaviour, then we are safe from social disapproval, from nosiness, from the pull and drag of social norms, from the shock or disgust of our peers. Who cares if I spend all day looking at immature cartoons, kitten vines, youtube video nasties, or questionable pornography, when there’s no-one there to question it? Within certain limits of blatant illegality (sharing child porn) or suspicious behaviour (following ISIS on twitter), we’ll probably get away with anything.

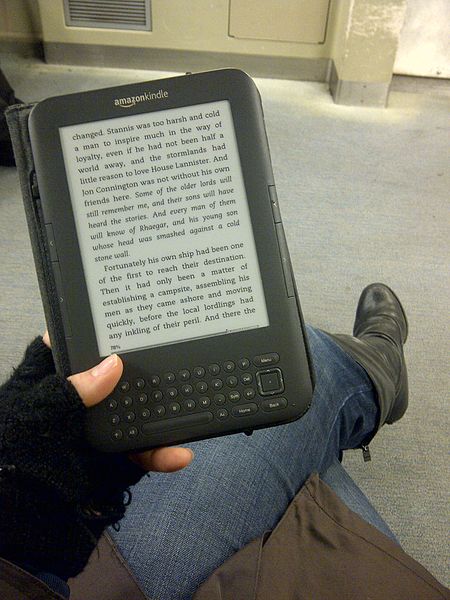

I thought of this as I read of the top twenty books downloaded on amazon, which people can read on their kindle or tablet, and the big difference between this list of ‘guilty pleasures’ and Waterstones’ top-selling paper books of the year. Popular e-books include Fifty Shades of Grey, a few Mills and Boon romance titles and four (four!) adult colouring books. Waterstones’ list includes more highbrow authors like Colm Tóíbin and Ian McEwan.

The implication is that we buy intelligent paperbacks to show off the front cover to the passenger sitting opposite us, but then download ebooks to indulge our more urges – reading about food, romance, and er… colouring in – safe from the sneering of our peers who can only see the generic grey underside of our Kindle.

By Mia5793 (Own work) [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons

This thought is interesting to sociologists because the power of social norms is a fundamental tenet of the entire discipline. Remove or at least dilute that power by shrinking our consumption space to that between our eyes and the screen, and the social world starts to look very different.

On the one hand, this might be empowering: minimising the space for social disapproval; reducing the scope for the judgements of others; making conspicuous consumption less… conspicuous. On the other hand, aren’t social norms the ‘invisible hand’ that maintain a functional and cohesive society? What happens when we reduce the power of social norms, and allow ourselves free reign to indulge our every desire in that ‘private’ space between user and screen?

1754-9469/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=9197a1a6ba8c381665ecbf311eae8aca348fe8aa)