Thinking About Domestic Partnerships

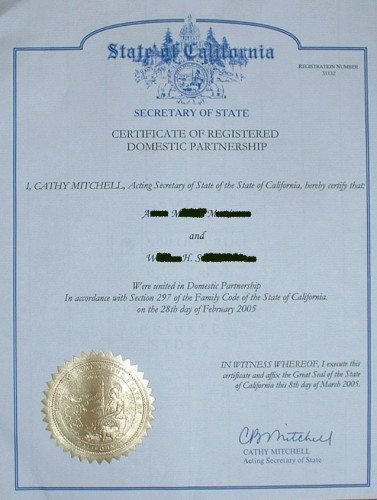

I left my home state of Florida for some very personal reasons: racism and nativism, extremist right wing politicians, fiscal conservatism (and the failing school and social systems it produces) – not to mention vigilante justice (thanks to the stand your ground laws) and face-eating druggies. When people ask about where I grew up, I’m not proud to answer. But this summer, it got just a tiny bit better. Florida, ever a bastion of political, religious, and moral conservatism, a state a long way from marriage equality, took a few small steps forward. Sarasota, my home county, along with several other FL counties, drafted a domestic partnership registry. By registering as domestic partners, couples (both same- and opposite-sex) can gain certain benefits—like end of life and emergency care decision-making and education choices for dependents—without relying on or having access to the institution of marriage.

Floridian counties are not breaking new ground in this legislative action. The idea of domestic partnerships emerged in the 1980s, and gained some ground in the decades that followed (see Traiman’s brief history). Many city governments and corporate policies provide for domestic partner benefits. Domestic partnerships have gotten overshadowed with a shift in activism and public discourse toward full marriage equality. Even though domestic partnerships may seem like an insufficient, “separate but equal” type solution, they do provide practical relief for real problems. As the child of lesbian parents, I understand the necessity of practical solutions—how to arrange for both parents to make health care decisions for me, or pick me up from school, whose health insurance could carry me, and so on.

What excites me about the reinvigoration of a discourse on domestic partnerships, though, is more theoretical than practical. It’s another chance to think about how we institutionalize our relationships, and to what extent we want to keep the nuclear family, the marital family, as the central ideal. Domestic partnerships are a way of recognizing and supporting alternative family structures. Many people believe that these registries and corporate benefits are “special rights” for the LGBT community. But in fact, most domestic partners are heterosexual. And some groups want to make sure that heterosexual people aren’t left out of the domestic partner registries. The Alternatives to Marriage Project and Unmarried America want to ensure straight people’s access to domestic partnerships. There are many reasons for straight people to enter into a domestic partnership—elderly people may choose not to get married in order to avoid complicating estates and wills, or to avoid loss of pensions; people may be politically opposed to marriage as an institution; people may not want to remarry after the loss of a spouse. And, Unmarried America reminds us, people should have the right to construct intimate, familial relationships that don’t necessarily imply the physical or sexual component that marriage implies (see Coleman’s essay on their site). While I’m wary when majority groups claim subordination/exclusion (like when white people complain of reverse discrimination, or men’s rights groups rally around their shared oppression), I do think there are important points here about the multiple and diverse reasons for entering into and staying in relationships.

We have constructed a highly romanticized, idealized notion of marriage and family. And institutionally, as a society, we seem highly committed to the nuclear, traditional, married family. In fact, even though they are excluded from the traditional model in most states, many LGBT couples deeply desire this traditional lifestyle. I grew up in an LGBT church denomination. Years back, a few people in the denomination suggested that they would like to have a holy union (a religious ceremony in the denomination, like a wedding, to substantiate a relationship in God’s eyes)…between the 3 of them. The event sparked a bit of a debate through the denomination and ultimately, no holy union would be performed for a triad. Only dyadic relationships would be officially recognized by a church. The irony here is, even those barred from marriage are influenced by its ideology.

Much of the energy of the LGBT movement has been devoted to the rather conventional goal of marriage equality. (I should say here that I am not trying to disparage this goal—everyone should have equal civil rights.) But marriage isn’t for everyone or every relationship. And outside the romantic (not to mention heterosexist, gender unequal) marriage ideal, there are many, many types of families that challenge the norm. These are straight, gay, bisexual, trans, queer, adoptive, single, extended kinship, etc. families. And they deserve recognition, stability (which results from institutional support), and some benefits too. This pushes us to think about families in more complex ways, escaping the simple structures suggested by sexual orientation-based, gendered marital model.

As sociologists, we are always looking for moments of active social construction, where the social processes that are so often invisible appear concretely in front of us. These legislative acts, like the debate that occurred around triads in my church, are exactly those moments. Seize them.

Further reading:

Traiman, Leland. A Brief History of Domestic Partnerships. Outhistory.org.

1468-0491/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=859caf337f44d9bf73120debe8a7ad67751a0209)