The Potential of Epigenetics for Sociology

A careful understanding of epigenetic mechanisms allows sociologists to include a new biological perspective into research designs – when it is incorporated carefully and not used casually or blindly as a deus ex machina explanatory device that is.

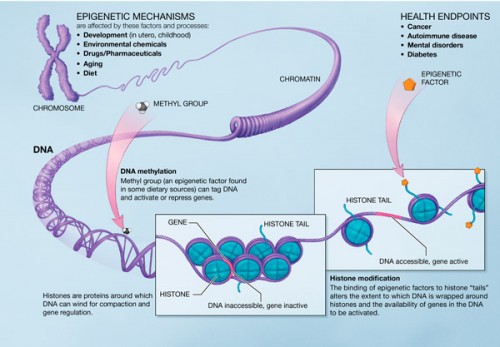

Epigenetics provides us with one of several “mechanisms by which social influences become embodied” (Kuzawa and Sweet 2008: 2). A promising place for sociologists to enter into this research or use it fruitfully is to examine how social environments and inequalities become embodied as epigenetic imprints, altering gene expression and consequently affecting a wide array of health outcomes. Additionally, while mapping the epigenome, epigeneticists are exploring differences in the plasticity of particular alleles at various points in the lifecourse. Could the inclusion of epigenetic biomarkers in sociological work allow for the separation of early life events from cumulative ones?

These mechanistic stories are bound to be messy, but such feedback loops and the enmeshment of social and biological processes are inescapable. With the knowledge and technology available today, we are far beyond oversimplified nature versus nurture debates. Many biologists who do epigenetic work realize that in order to get a complete, complex mapping of these mechanisms, the social needs to be included. These biologists view sociological and cultural variables as more of a signal rather than just contextual noise. Sociologists should not only collaborate with such researchers, but also help shape what these projects look like.

Further, sociologists should be aware of developing epigenetic discourse and how it is being received in the media. Over the past year or so, non-scientific magazines from Time to Newsweek have picked up on epigenetic findings, publishing articles for the general public on the topic. However, not all of this reporting clearly emphasizes epigenetics’ softening of geneticization’s hard line determinism. Further, some of it mistakenly over-emphasizes our agency in the changing of our own and our future generations’ genetic code. Sociologists should be aware of such reporting, lest it follow the route of the powerful, persuasive, and pervasive hold the narrative of geneticization has in everyday, non-scientific talk (Chaufan 2007) – especially since general understandings of genetic findings often easily allow genetics to take the stage as a deus ex machina of causal efficacy despite findings that clearly prove otherwise.

DNA: How You Can Control Your Genes, Destiny

DNA: How You Can Control Your Genes, Destiny

1728-4457/asset/PopulationCouncilLogo.jpg?v=1&s=03074651676b98d6b9d0ef1234bd48fe7ff937c3)

While the nature v. nurture debate has always been an oversimplification, since few phenomena fall clearly on either side, I’ve always found a distinction a useful starting point to explain sociological analysis to undergraduates. I use height as an example. Most of us consider height genetic, but if we think about it a moment we also know that nutrition plays a role – so that an individual’s height is a combination of nature and nurture. I then move on to explain that for a social group height is heavily dependent on social factors.

That being said, I’m unsure how epigenetics fits in. In other words, would you say that the preceding example is problematic because it reinforces a split between nature and nurture – treating them as two separate independent factors when in reality, genes and environment are not as truly independent as my example makes them sound?

I think your comment refers to a language and explanation issue that is often dealt with when trying to shift taken for granted lenses. In order to begin an explanation showing the connection between two once perceived as separate but actually quite entangled entities, it’s difficult not to start with the separation.

For basic explanatory purposes, familiar “splits” between “factors” can be a helpful way to introduce the relationship between the two usually perceived as separate entities. However, next immediate steps should locate other referents for the terms we usually perceive as being attached to things like diet and height (how the social plays a role in the biological and vice versa). Epigenetic discussions about this relationship tend to be more nuanced in detailing both social and biological aspects of these feedback loops on multiple “levels.”

Depending on the purpose of one’s explanation, enmeshment of causation between “biological” and “social” factors can seen as large and seemingly reified or indefinitely smaller and complex – for example explanatory factors could be as “mezzo” as diet and height, as “macro” as culture and bodies, or as “micro” as a particular cell function and parenting style in early childhood.

That being said, the relationship between the factors you employ are used as explanatory devices in epigenetic explanations. In particular, the role that famine in earlier generations plays in transgenerational transmission of genetic expression related to height is an oft used example in epigenetics documentaries and articles poised towards the general public (usually the Dutch “Hunger Winter” example)- an embodiment of environment over time through to those who have not actually experienced it. Such epigenetic explanations of the relationship of these two factors you use in your discussion, diet and height, differ from your explanation in how they detail the mechanisms and complexity of feedback loops that are occurring as the social becomes embodied.