Teaching Feminism 101

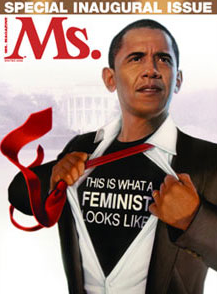

For many people, the “feminist label” is a problem. For some, the term is stigmatized. For others, the phrase is outdated. And many young people reject being identified as a feminist, fearing the label is so dominating it will minimize the multiplicity of their other social identities. Thus, despite the support film stars, musicians, and even the President of the United States, feminism is still problematic for many men and women today.

In a previous posting, I described my surprise in interviewing female artists (who all produced work that critiqued and challenged gender expectations and asymmetry) when these women refused to label themselves or their work as feminist. As I concluded that project I found myself left with more questions than answers. I asked if there was a possibility that the fight for gender equality could exist on a feminist continuum as some scholars in women’s and gender studies have suggested? And would allowing those who do not identify as feminists to be recognized under the umbrella of feminist ideology improve the fight for an egalitarian society or would it further stigmatize those who work for gender equality across the globe?

These questions have returned to the forefront of my mind as I’ve transitioned from a student of sociology of gender to an instructor. Recently, I have had the opportunity to speak in depth with undergraduate students about gender and feminism in the United States today. Similar to my discussions with female artists, I found undergraduate women, even those deeply committed to social justice and universal equality, were hesitant to identify as feminists, frequently arguing that the label was too limiting in contemporary society.

I understand this resistance. When I was first introduced to feminism in the 1990s, I too rejected the label preferring to be identified as a “humanist.” However, my rejection of the feminist label did not last long. I had energetic and engaging undergraduate professors who made being a feminist appealing despite the cultural anti-feminist scripts I had been exposed to throughout my childhood. I made friends in these classes, and together we enthusiastically embraced feminism. For me, the turning point was interacting with instructors that became mentors.

Today, I find myself standing at the front of the classroom attempting to reproduce what my undergraduate professors seemed to highlight so effortlessly. Despite the apparent casual approach of my instructors, I believe they each made strategic choices related to their presentation of feminism. First, they all focused on intersectionality and the diversity of feminist experiences. From the beginning, I understood that not all women experience gender, sexism, or inequality in the same ways. Reading bell hooks’ Feminist Theory as well as Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s classic novel The Yellow Wallpaper and Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands illustrated a spectrum of feminist points of view.

Second, my instructors clearly defined feminism and provided evidence that feminism was not a “hate movement” or “anti-men.” The majority of my female instructors were married to male partners. And one of the most knowledgeable feminist theory professors I had was a man. Yes, I read Valerie Solanas’ S.C.U.M Manifesto but I clearly remember the class discussion on that work focusing on the difference between Solnas’ writing and the Merriam-Webster definition of feminism as “the theory of political, economic, and social equality of the sexes.” We focused not on punishing men but rather on discussing how to create equal opportunities for women through examining the diversity of women’s lived experiences.

Third, not one of my undergraduate professors suggested men and women are, or should be, the same. For example, when we discussed biological difference, no one denied the reproductive difference between men and women or that on average men had more upper body strength than women. However, my instructors did question how these small biological differences evolved into social norms and values. We examined the social structures that create difference between boys and girls in education (Thorne 1993). We discussed difference in the workplace (Eisenberg 1999). We explored difference in the domestic realm (Hochschild 1989). Then we made the picture more complex by addressing additional issues of race, class, sexuality, nationality, and religion. As we looked at how feminist ideology, how the fight for political, economic and social equality could alter gender inequality in in education, the labor market, and the domestic sphere, never once was it suggested that equality meant the creation of an androgynous world society.

Finally, we discussed our own individual and personal experiences as gendered beings. We described our personal experiences of inequality and privilege both in class discussion and in reflection papers. We discussed our diverse reactions to the representation of men and women in the media, in politics, in the arts, in religious doctrine. And we compared our experiences.

My undergraduate courses made me want to re-identify myself, not just as a feminist but also as an anti-racist, as an LGBTQIA ally, as a social justice advocate. Feminism taught me work for political, economic, and social equality. Feminism opened my eyes. As an instructor I hope I can open my students’ eyes. And even if I cannot convince my students to accept the feminist label, I hope I can use feminism to teach them to fight for a more egalitarian world.

Further Reading:

Anzaldua, Gloria. 2012. Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 4th edition. Aunt Lute Books.

Eisenberg, Susan. 1999. We’ll Call You If We Need You: Experiences of Women Working Construction. Cornell University Press.

Hochschild, Arlie. 1989. The Second Shift: Working Families and the Revolution at Home. Penguin.

hooks, bell. 2000. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. 2nd edition. South End Press.

Thorne, Barrie. 1993. Gender Play: Girls and Boys in School. Rutgers University Press.

1520-6688/asset/Capture.jpg?v=1&s=b5076c49a7d1c5f1b9cf0dd9cd292394a3be81cc)

While what is behind most interpretations of feminism is about fighting for a more just and equal world, I do agree the term itself is outdated and only serves to reproduce a harmful binary system and an us-and-them mentality. It becomes meaningless to talk about biological differences between ‘men’ and ‘women’ when you realise that people come in more varieties than two.

I agree. People definitely come in more than two varieties. However, I would argue that as feminist scholars have augmented and expanded theoretical perspectives, they have challenged (and continue to challenge) the hegemonic. And breaking down the hegemonic enables us to critique a binary system.

Clearly, one of the limitations of my posting was that I only focused on my students’ critiques of feminism and reflected on how my personal undergraduate professors addressed these critiques. My students frequently like to bring up biological differences when discussing gender equality. These comments always remind me of one of my undergraduate classes when a student told the professor she believed feminists wanted men and women to be the same and everyone knew men and women were different. I remember my professor pointing out that biological differences are minute compared to the ways in which these small differences become embedded in social norms, values, and structures, often reproducing inequality.

Today, I think we can expand on that statement and use critiques related to biological difference to, as you pointed out, further critique the binary. Your response made me realize that when students bring up biological difference there is an opportunity to discuss diversity and further break down the hegemonic and the binary because I do not believe feminism is about “us-and-them.” Rather, I believe it is about equality for all.

I’m not critiquing what feminism has done, or is doing, but rather pointing out the actual term ‘feminism’ is outdated for what ‘feminism’ is today, broadly speaking, but also the more that it can do via another term that avoids reproducing binary thinking. Feminism/masculinism? masculinity? Whichever way, I think it reinforces a binary, most particularly for people who have not studied feminist theories and for the people who most need to understand/learn about gender inequality.

Of course feminism is not *about* an us-and-them perspective, but unfortunately I believe the term itself starts off/creates this mentality for many.