Speaking Globe-ish

An ESL Classroom. Somewhere. By Tallersperlallengua (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) or GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html)], via Wikimedia Commons

My discomfort mostly stems from the historical reasons for the rise of the English language. This was the largely unedifying story of colonial conquest on the part of the British in the nineteenth century – gunboat diplomacy, slavery, dispossession; followed by economic and cultural imperialism on the part of the United States in the twentieth – Hollywood, MacDonalds, Coca-cola. English language’s hegemony is a constant reminder of this often quite grim history.

Like it or not, for native speakers of English, that historical legacy provides us with significant advantages in the present day. I spent two years as an ESL teacher in South Korea, where, along with Japan and China and other East Asian countries, all that is required of applicants applying for ESL jobs is a university degree and the right passport (USA, UK, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, or South Africa). Teaching experience and qualifications, surprisingly, often count for little. For thousands of young graduates from native-english countries, there are well-paid, well-respected jobs out there, beyond (and, to lesser extent, within) the recession-stricken West; jobs which don’t exist for other equally talented young people who happen not to be born speaking English. As well this being unfair, it’s also far from self-evident that (native) english-speakers necessarily make the best English-teachers, an assumption that seemed to have taken hold in many Korean schools. My European friends for whom English is a second language usually know far more about English grammar than my native-speaker friends, who are usually completely ignorant of the rules which make up their mother tongue.

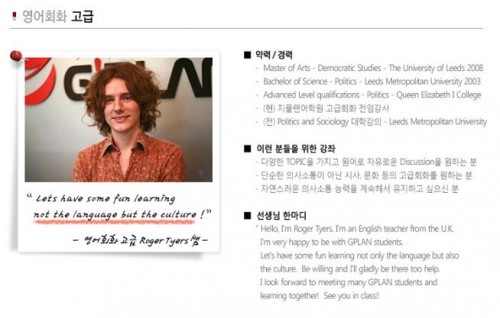

This is from the website of the language institute I worked in, when I worked in Korea. (They may have used just a little artistic licence). Laughing is permitted.

However unfair it might be, the fact I was born speaking English is undeniably advantageous, at least in the jobs market. It’s also a huge help in academia where English is the default language. Sadly it appears that this good fortune is often treated with complacency, with fewer and fewer British students choosing to study other languages at A-level or degree level, leaving to as many as eleven universities closing their foreign language departments over the past fifteen years. This trend has alarmed the British and US governments, now discovering that there are not enough skilled multi-linguist applicants to fill jobs in overseas embassies or at multi-lingual institutions like the EU or the UN. Diplomats in both Britain and the States have expressed concern that this lack of foreign language speakers in sensitive jobs, where communication skills are vital and issues of international relations are at stake, may even constitute a threat to national security.

Beyond the economic and diplomatic benefits which learning second languages brings, there are numerous cultural benefits as well. Globalisation has brought us greater access to foreign music, film, and TV than ever before, but to really understand a country, one needs to understand its language. You may have seen the video a dozen times, but do you really know what the ‘Gangnam Style’ lyrics are actually about? (there’s actually a bit more social comment there than you might expect). Even learning just a little of a foreign language can unveil relationships of class, hierarchy and gender relations which are embedded in grammatical forms and common phrases.

Furthermore, learning foreign languages makes one notice the differences with one’s own, and gives an awareness of the complex socio-cultural factors which lie beneath language and have an interdependent relationship with it. One doesn’t need to be a sociolinguist to appreciate this. As Goethe said: “Those who know nothing of foreign languages know nothing of their own.” It is my fear that less people learning foreign languages could breed an Anglo-centric, parochial and inward-looking psyche, one which encourages ignorance and detachment from the rest of the world. (I’m reminded of UKIP leader Nigel Farage’s comments on feeling awkward hearing non-English speakers on the train).

The facts of history have conspired to make English our global language, at least for now. It’s too late to change our imperial past. We should, however, remind ourselves to be grateful for the extra jobs and opportunities which English’s hegemony brings to us Anglophones. We should also not allow complacency and laziness prevent us and our children learning other languages, and taking an interest in the big, wide world beyond the Anglosphere.

1754-9469/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=9197a1a6ba8c381665ecbf311eae8aca348fe8aa)