Prize Winning Fictions

On Tuesday, Marlon James’ A Brief History of Seven Killings was awarded the Man Booker Prize for 2015 at the City of London’s Guildhall (an institution about which I wrote for Sociology Lens last year). James’ book is an imagined retelling of the attempt made on Bob Marley’s life in 1976, and the first novel by a Jamaican writer to win the Prize, which now comes with a £50,000 cheque, having been introduced with a purse of £5,000 in 1969. Jamaican poet Kei Miller has suggested that James’ win heralds a new era in Caribbean writing, rejecting the apparent choice between the poles of ‘sacred’ reverence and gentle, mocking ‘satire’ that seem to have characterized Caribbean fiction to date. This new era, argues Miller, is one propelled by “a new generation of writers who had all the resources of creolised Englishes and the uncanny stories that they witnessed first-hand growing up on the islands, but who would also gain other, technical, resources from taking creative writing courses across the world and forming a community with other writers.” And here, in James’ win, and Miller’s response to it, can be found all that has, perhaps surprisingly, made the Booker Prize a favourite topic not only of literature professors, but of sociologists and management scholars too.

There is, first off, the disquieting tension between commerce and art that a £50,000 purse (and corporate sponsorship) brings with it. Richard Todd’s 1996 work on the Booker, Consuming Fictions, contained the claim that being shortlisted for the Booker Prize (as it then was) increased sales by around 5,000 copies, and winning meant around 40,000–80,000 ‘extra’ copies sold. The Prize, argued Todd, helped to generate a “commercial canon” (p. 71), plucking literary talent from the Commonwealth (or, since 2013, anywhere in the world) and producing, in one go, accolades for an art form and a boon for the book trade. (Hilary Mantel’s win for the already commercially successful Wolf Hall in 2012 was not, therefore, without controversy!) And hence it is perhaps unsurprising that so many sociologists and organization theorists have turned to Pierre Bourdieu, and his writings on art, taste and class, and field theory, in their efforts to make sense of the (Man) Booker Prize.

Narasimhan Anand and Brittany Jones, both management scholars, have approached the Booker Prize via Bourdieu’s field theory, conceived of as a set of hierarchical spaces through which actors may move (displacing others in the process), where “the thing that enables field participants to move up in the hierarchy of a field’s topography is capital” (p. 1037), either social, cultural or economic. Anand and Jones’ argument is that the Prize is a kind of tournament of value, a ritual that reifies and engenders new cognitive categories that influence the structure of a field. Examining the archives of the Booker Prize from 1969–1982, they suggest that acts within the ritual space of the Prize ceremony have not only helped to re-frame literature in competitive terms (with the language of “photo-finishes” that emerged in press coverage of the 1981 battle between Salman Rushdie and D.M. Thomas), but have revalorized and reconfigured the literary canon itself. Following Rushdie’s 1981 win for Midnight’s Children, they argue, the imperial nostalgia of Booker Prize-winning novels like The Siege of Krishnapur and Heat and Dust was set aside, and “what emerged as the Booker canon instead was the postcolonial novel, written from the vantage point of the immigrant, the exile, and the colonized” (p. 1053).

The literary prize is a curious beast with a “double reality” at its heart, argues English professor Stephen Levin. The aesthetic choices made by the Booker Prize’s judging panel “modulates its status as both a passive reflection of a bland globalism and an active agent of social change and engagement” – or, put differently, the prize has a “Rorshach character,” becoming a site for framing ‘World literature’ or ‘Indian literature’ and for intensifying the vulnerability of “context–sensitive cultural forms to translations that homogenize the diverse tonalities” of world Englishes (p. 478). That which Kei Miller feels is recognised in Marlon James’ Booker win – the creation of a new generation of writers influenced as much by creolised language as by globalizing writing workshops – is also, Levin might suggest, something to be wary of.

But Anand and Jones’ take on field theory, and the literary prize as a ritual in which new categories (commercial literary fiction, or postcolonial fiction) are enunciated and valorized does not exhaust what Bourdieu seems to have to say about the Booker. Sharon Norris has explored in more detail the class distinctions animating Booker Prize decisions, and the question of “whether the ‘best novel’ is assessed on aesthetic grounds or in relation to social values (insofar as it is ever possible to separate the two)” (p. 141). Early Booker judging panels and shortlists alike were brimful of Oxbridge graduates, but in the early 1980s the University of East Anglia began to exert an influence, with Malcolm Bradbury directing UEA’s Creative Writing MA and the Booker judging panel, and Kazuo Ishiguro (a graduate of Bradbury’s course) winning in 1989. (In the 2000s, the judging panel’s composition, and the background of several winners, tipped back towards Oxbridge.) As Bourdieu argues, “all judgements on culture [are] at the same time, affirmations of the right to make such judgements” (p. 147). The Booker is not merely any old field in which new categories of worthy fiction are stabilised, it is one in which a select and specific social elite exercise their right to set aesthetic standards.

Thus while the awarding of the Prize to Rushdie in the 1980s might, for Anand, Jones and some other observers, reflect a turn toward ‘the vantage point of the immigrant, the exile, and the colonized’, Ana Cristina Mendes has suggested that Aravind Adiga’s win for The White Tiger (2008) constituted a revitalized exoticism. Mendes describes Adiga’s novel as a “revamped portrayal of a Dark India,” which was nonetheless described by chair of the Booker Prize judging panel, Conservative MP (and Cambridge graduate) Michael Portillo as “an intensely original book about India that is new to many of us…in many ways perfect.” Similarly, Ken Barris has hinted that the inclusion of Damon Galgut’s The Good Doctor on the 2003 Booker shortlist, and the victory of J.M. Coetzee’s Disgrace in 1999, “suggest[s] that books which predict failure for the new dispensation most centrally define the properties of South African political writing under present conditions, at least as far as the UK market is concerned” (p. 35). (In Galgut’s novel, we find black incompetence in the character of Dr Ngema, Afrikaans state criminality in Colonel Moller, and only the young Anglo–South African Waters is more-than-mediocre, albeit present as naïve for being hopeful.)

These are rather serious charges, worthy of equally serious contemplation. Given the capacity for the Booker to increase sales, and to reproduce the category of ‘commercial literary fiction’ – through the consumption of which one can signal the possession of a certain quantity of aesthetic distinction – the troublingly narrow class positions and perspectives on the post-colonial Commonwealth possessed by the judging panel end up being amplified tremendously through the Prize-giving ritual. (None of this, I should add, is intended as a comment on James’ novel which I haven’t yet read, and, as such, would not presume to pass judgement on.) Returning to Levin’s take on the double reality of the Booker, it could perhaps be argued that awarding the prize to postcolonial writers allows ‘the West’ to settle down not to contemplate India, South Africa or the Caribbean, but “its latest reinterpretation of itself” (Francesca Orsini, cited in Levin, 2014, p. 488).

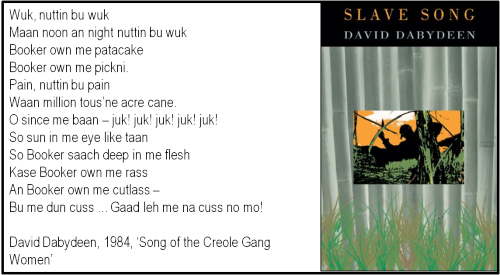

One thing relatively absent from the press commentaries on James’ win so far is the Booker–McConnell corporations’ history in the Caribbean. (Booker–McConnell founded the Prize in 1969, and when the Man Group took over in 2002, they kept the name.) In David Dabydeen’s poem ‘Song of the Creole Gang Women’ reproduced in the header image of this blog, the lines ‘Booker own me patacake / Booker own me pickni’ are translated by the author as ‘Booker owns my cunt/Booker owns my children’, and reflect the unambiguously brutal past of the Booker agricultural group in the Caribbean (perhaps, especially, in Dabydeen’s Guyana). That this does not seem worthy of mention to many journalists covering the contemporary Prize reflects, perhaps, Norris’ Bourdieusian explanation for Booker’s decision to inaugurate a literary prize in the 1960s: “sponsorship is essentially the exchange of capitals, the answer is clear. Of all the options, this was the one that promised greatest returns, by way of symbolic profits” (p. 142).

Further Reading

Anand, N. and Jones, B.C. (2008) Tournament Rituals, Category Dynamics, and Field Configuration: The Case of the Booker Prize. Journal of Management Studies, 45(6), pp. 1036–1060.

Barris, K. (2005) Realism, Absence and the Man Booker Shortlist: Damon Galgut’s The Good Doctor. Current Writing: Text and Reception in Southern Africa, 17(2), pp. 24–41.

Levin, S.M. (2014) Is There a Booker Aesthetic? Iterations of the Global Novel. Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, 55(5), pp. 477–493.

Mendes, A.C. (2010) Exotic Tales of Exotic Dark India: Aravind Adiga’s The White Tiger. Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 45(2), pp. 275–293.

Norris, S. (2006) The Booker Prize: A Bourdieusian Perspective. Journal for Cultural Research, 10(2), pp. 139–158.

1540-6237/asset/SSSA_Logo-RGB.jpg?v=1&s=c337bd297fd542da89c4e342754f2e91c5d6302e)