Grunge, Britpop, and the end of mass cultural movements

http://www.seattlepi.com/local/seattle-history/article/Kurt-Cobain-suicide-scene-previously-unpublished-4410890.phpPhoto: Mike Urban/Copyright MOHAI, Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection

This year marks twenty years since 1994, a year that saw two key movements in western youth culture – the end of US grunge, marked by the suicide of Nirvana’s singer and songwriter Kurt Cobain, and the start of the Britpop, marked by the release of seminal albums Parklife by Blur, and Definitely Maybe by Oasis. Although these start/end points are rather arbitrary, the media love to create and discuss an anniversary: it is something they can plan for with ease, cobbling together old footage, re-releasing articles, obituaries and reviews to a guaranteed audience of people who were ‘there’ lapping up every opportunity to be transported back to their youth. Myself included.

Is there any sociological value in looking back to the music of the early nineties? I would argue that grunge and Britpop were perhaps the last two real, cohesive movements in popular music culture before the rise of the internet and the subsequent fragmentation of tribalism in musical culture. This anniversary need not just be an excuse for nostalgia, but is also an opportunity for taking stock of the social, technical and cultural changes which have slowly crept upon us over the last two decades.

What did these movements look like? I generalise here, but followers of grunge, as well as sharing a similar music palette, were known for a particular slacker, quasi-Goth aesthetic fashion (long bleach-dyed hair, tartan shirts, thumbs poked through sweater-cuffs), and a nihilistic, cynical, alienated worldview informed by a post-Reagan/Thatcher ideology of meaningless consumerism. Jonathan Freedland, writing Cobain’s obituary in The Guardian described Grunge as “bereft of the idealism of flower-power, or even the exuberant iconoclasm of punk… a movement entirely without coherent politics. Hippies and punks were both public movements, whether they were strumming to stop the Vietnam war or spitting about Anarchy In The UK. Both believed in the possibility of change. But Cobain, like the 20-plussers who listen to him, was private and self-absorbed. “What is wrong with me?” he sang. “I’m so tired, I can’t sleep.””

Of course, Nirvana and Grunge’s rise to global prominence meant that they could not long be confined to the young grunge-kids tribe/market (delete as appropriate). The music’s inevitable crossover into mainstream, FM-radio/MTV success meant that before long, bankers, housewives and middle-aged office workers started listening to Nirvana as well. But the early-adopters, the ‘vanguard’ of Grunge were a particular group of people who were defined by what they were against, as much as what they were for. Like all subcultures, it was supposed to be exclusive. Once it got too popular to be exclusive any more, something was lost. No doubt Cobain felt this uncomfortable shift more than anyone.

Similarly, the rise of Britpop was, in many ways, a reaction against grunge, a musical movement which wanted to identify more with an English lyrical culture of story-telling and reflection on its own cultural landmarks (the Kinks, the Beatles), than to (a)pathetic American grunge. Oasis songwriter Noel Gallagher said “Nirvana had this song called ‘I Hate Myself and I Want to Die’, and I thought ‘I’m not f*cking having that.” As well as differences in the music, fashion-wise the long cardigans and lumberjack shirts of grunge were replaced by Britpop’s tracksuit tops, kangol hats and shorter (though not always better) haircuts.

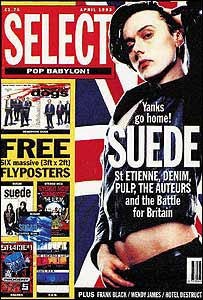

‘Yanks Go Home!’

http://unclee.files.wordpress.com/2012/02/select-mag.jpg

And within Britpop, there were exclusive divisions too. The famous chart battle in August 1995 between Blur and Oasis – which in a way marked the beginning-of-the-end of the movement – quickly divided my high school classroom between Blur fans and Oasis fans. Liking both bands was suddenly not an option (not publicly, anyway).

In this way, Britpop and Grunge and their perceived ‘otherness’ places them in a long line of musical-cultural movements in the West including the mods, rockers, hippies, punks and skinheads, all of whom defined their own version of ‘cool’ in opposition to outsiders. Even the very word ‘cool’ is alleged to derive from followers of doo-wop music in post-war USA, who wanted to differentiate themselves from jazz-fans who used the word ‘hot’ to refer to good music. Exclusivity is key.

Since the nineties, it is hard to discern a similar musical movement which has united and divided young music fans in quite the same way, at least in the white anglophone culture with which I’m familiar. Movements now seem less cohesive and sub-cultural cleavages are more blurred. One reason for this is that in the 1990s, a few key magazines (in the UK, the NME and now-defunct Melody Maker and Select), radio stations and TV channels (especially MTV) were able to mobilise fans and customers towards a few key cultural products. Now, we have countless online blogs, web-based music sources and social media; print media is in decline, and the pre-internet gatekeepers like radio playlisters, newspaper editors and TV producers, while still powerful, are far less capable of manufacturing excitement and interest in a few key artists and cultural products than they once were. Music is as popular as ever, but consumers are not coalescing around a few artists in the same way: the ‘big hit’ has been replaced by the ‘long tail’.

Ours is a landscape of cultural hybridity, an internet-facilitated eclectic postmodernism where tastes are varied and our musical-cultural identities complex. Zygmunt Bauman describes a world of ‘Liquid Modernity’, with the contemporary individual as a nomad who flows through the world like a tourist, changing and exchanging habits of work, relationships and cultural signifiers as much as his wallet allows. I thought of Bauman when I recently read a music journalist’s article on the changing state of the Reading rock festival in the UK, which testifies to how the factional subcultures of the early 1990s (with visibly different tribes of goths, metal-fan and indie-kids) have been replaced by young festival-goers who are more visually homogenous, yet whose tastes may range from heavy metal to electronica and indie without any sense of subcultural exclusivity prohibiting them.

A mix of tribes at Glastonbury music festival. By Fussyonion [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

To Nirvana, Oasis, Blur and the rest: Thank you for the music, and the memories. The world’s become a more confusing and complex place, but perhaps that’s for the better.

References

Bauman, Z. (2000) Liquid Modernity. Cambridge

Warde, A. (2005). Consumption and Theories of Practice. Journal of Consumer Culture, 5(2), 131–153.