Avery Gordon's "Ghostly Matters" and the Haunting of Sociological Research

I recently stumbled upon a unique analysis of the construction of social reality. In Avery Gordon’s Ghostly Matters, haunting is a method of sociological research. She argues, “To study social life one must confront the ghostly aspects of it” (7). Ghostly Matters is her attempt to understand the complexities of social life through an analysis of the hauntings surrounding Sabina Spielrein, the desaparecido of Argentina and the lingering impact of racial slavery during the Reconstruction period in the United States. Her book might be a conceptual call within the field of sociology to understand that which it represses, but her approach is truly interdisciplinary, in that she seeks to create a something “that belongs to no one” (ibid).

Gordon begins her exploration into the world of haunting by outlining the limitations of positivistic sociological studies. She questions contemporary methods of examining the relationships between knowledge, experience and power. Suggesting an alternative approach, that haunting can be used to describe the screaming presence of that which appears not to be present, Gordon argues that “ghostly matters” are signifiers of what is missing and what must be examined. In addition, she challenges the reader to consider alternative methods and forms that can produce reality and truth (23-24). In this project Gordon looks to Literature, which she states is “riddled with the complications of the social life” (27) and not restrained by disciplinary conventions. To illustrate the power of Literature as a vehicle to draw out sociological information, Gordon turns to Luisa Valenzuela’s Como en la Guerra/He Who Searches and Toni Morrison’s Beloved. But first she examines the haunting of Sabina Spielrien, a “detour,” a “distraction,” the women missing from a photograph who initiated Gordon’s project.

In 1904, a young Russian woman is taken to Zurich to be treated for schizophrenia. She falls in love with her analyst, Carl Jung, and the doctor falls in love with his patient. She is cured and ultimately becomes a scholar of psychology. As the relationship fell apart, Sabina Spielrein became entangled in the Jung’s relationship with Freud and her work likely influenced the history of psychoanalysis. Yet, Spielrein is not among those in a photograph taken at the Weimar Congress in 1911. Her absence from the photograph haunts Gordon. Her diaries and letters haunt Gordon. They illustrate repetitive nature of ghostly matters, the blindness of the educated, the limitations of representation, the importance of the uncanny, and the reality of being haunted.

According to Gordon, the recognition of a haunting is a means of knowing what has happened or is currently happening (63). Therefore, to thoroughly understand the state terror and desaparecido of Argentina requires one to contemplate ghosts and hauntings. Gordon uses Luisa Valenzuela’s Como en la Guerra/He Who Searches to highlight a different kind of knowledge. This knowledge, which was also represented in the pleas of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and ignored by the Argentine Psychoanalytic Association, middle class and professionals of the country, shows that disappearance is a state of being. Disappearance is not the same as death, as death is past and disappearance is present. Gordon points out that Valenzuela’s character AZ represents the blind, middle class, psychoanalytic professional. He looses the woman he loves but gains the ghost that ultimately awakens him to reality. The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo also wanted to awaken Argentineans to reality. They saw reality because of their understanding of haunting and its role in society and their silent screams, their photos of the eyes, mouths, and faces of the desaparecido, represent what Walter Benjamin called a profane illumination.

While a haunting can emphasize the disappeared, Gordon suggests it can also call our attention to that which lingers, as in the impact of racial slavery and the failures of Reconstruction. In the 19th century, biographical slave narratives were used as a mechanism to articulate the slave experience to a primarily white (and often female) public. Gordon argues that these narratives, much like the discipline of sociology, combined autobiographic, ethnographic and historic elements to further a political agenda. However, the political nature of these narratives required that they be not only believable but also consumable (145). Toni Morrison’s Beloved fills in the gaps left by slave narratives. She refuses to provide proof of the humanity or believability of her characters. She refuses to create a story that can be reduced to a series of causes and effects. In addition, Beloved can be understood as a new sociological reality; a reality that embraces the power of hauntings and the lingering power of the past. One way Morrison illustrates the power of haunting is through social memory, or rememory. Gordon reads Morrison’s rememory as social relations “prepared in advance and…linger[ing] well beyond our individual time, creating that shadowy basis for the production of material life” (166). Memory haunts. Therefore, ghosts do not live in some spirit world, but in the real everyday world struggling with their own ghosts and desires. The characters in Beloved live with lingering rememories of Sethe’s murdered baby, symbolically illustrating the ways in which Americans today live with the rememories of slavery, racism and the failures of Reconstruction.

Throughout Ghostly Matters Avery Gordon haunts the reader with repetition, ghostly illustrations the intermingling of “fact” and fiction and a truly interdisciplinary method for negotiating what is seen and what is known. Her analysis of the words of Sabina Spielrein, Luisa Valenzuela and Toni Morrison produces a work that creates the very structure of feeling she argues is embodied in ghostly matter.

Further Reading:

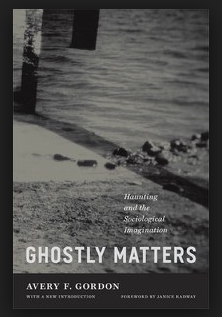

Gordon, Avery F. 2008. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. 2nd edition. Univ Of Minnesota Press.

Morrison, Toni. 2004. Beloved. Reprint edition. Vintage.

Valenzuela, Luisa. 1987. He Who Searches. Elmwood Park, IL: Dalkey Archive Press.

1099-0860/asset/NCB_logo.gif?v=1&s=40edfd0d901b2daf894ae7a3b2371eabd628edef)

“Yet, Spielrein is not among those in a photograph taken at the Weimar Congress in 1911. Her absence from the photograph haunts Gordon. Her diaries and letters haunt Gordon.” It is because Gordon knows about Spielrein that the latter’s absence from the photo haunts her. It is because the relatives of the “disappeared ones” knew the disappeared ones that they could generate a sense of ‘being haunted’ among non-relatives.

“Therefore, to thoroughly understand the state terror and desaparecido of Argentina requires one to contemplate ghosts and hauntings”. It is crucial that some people (the ones who know about the disappeared ones) work to force the ignorant and the bystanders who would prefer not to know to bring the “disappeared” into their knowledge and then into central focus.

To talk of “alternative methods and forms that can produce reality and truth” is for me to produce mystifying talk. The ‘hauntings of the disappeared” is a work of people in the present not changing the reality of the past but working to tell the truth which has been hidden and denied (and often continues to be so, see climate denial). If this work of recovering some truth about the past is successful in changing the reality of massive denial to a new reality of at least partly-recovered memory, then “ghosts and hauntings” as a work of motivated contemporary action has been successful.

But there are no ‘ghost-effects’ , there are no ‘haunting effects’, without people trying to trouble existing hegemonies of unconsciousness. A mode of talk that makes this difficult to see or think is itself guilty of concealing the reality of the real work of real militants, and generating an amnesia of its own.,

Hi,

Nice summary of Avery Gordon’s work. Can you please share the name behind the handle so I can cite in my paper.

Many thanks,

Jan

Hi,

Nice summary of Avery Gordon’s work. Can you please share the name behind the handle so I can cite in my paper.

(rademacher)

Many thanks,

Jan