A Look at Domestic Violence Related Asylum Cases

Last month, a Guatemalan woman, N-S-, won her domestic violence based asylum case after seven years in the United States immigration court system. Her case is similar to the story of many other women who flee their countries in order to receive protection from their abusive husbands. Until recently, courts rejected these types of claims, arguing that their issues were personal, not cultural issues (see Sinha 2001). Now, with the help of organizations like the Center for Gender and Refugee Studies at UC Hastings, it seems like more women receive favorable outcomes when their cases are heard in court (though the total number remains unknown since the asylum statistics are not disaggregated by type of persecution).

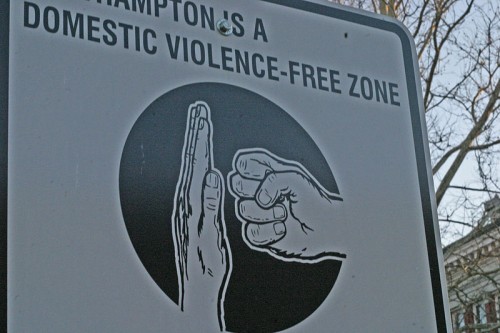

Domestic violence based cases usually involve a woman from a “Third World” or “developing” country migrating away from her husband to a “First World” or “developed” country, where she can receive refuge. This assumes that countries like the U.S. can provide a safe haven against domestic abuse. Yet, despite legislation and better police enforcement, many U.S. women (studies suggest at least one in four) will be the victims of domestic abuse at some point in their life course. Like many countries, the U.S. still shows high rates of domestic or intimate partner violence.

Incidentally, it is possible that the high rates of domestic violence in the U.S. actually contributed (and continues to contribute) to the denial of many domestic violence related asylum claims. In order to make a legitimate asylum case, an individual must prove a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, nationality, religion, political opinion, or particular social group. Given the cultural history of domestic abuse in the U.S., it might be difficult for immigration officials to rule that the violence in these cases rises to the level of persecution. Many women have hit a wall when making asylum claims because they cannot prove that they are members of a particular social group which has been culturally persecuted.

Take the case of R-A-. Her case was denied for many years because she could not prove that she was part of a group of “Guatemalan women who have been involved intimately with Guatemalan male companions, who believe that women are to live under male domination” (http://www.justice.gov/eoir/vll/intdec/vol22/3403.pdf, page 917). The court went as far as to say that she was the only woman abused by her husband, thus making her case a personal issue, not a cultural problem. This outcome in not surprising; it makes sense that the U.S. would interpret domestic abuse as an individual problem. To admit that domestic violence is a cultural problem would mean a condemnation of U.S. culture as well. Fortunately, the tides have turned and many immigration officials will grant asylum to women who are victims of domestic abuse. In fact, R-A- was finally granted asylum after nearly 10 years of litigation in 2009.

While I celebrate the asylum victories of these women, I am cautious about them, too. Many media sources and even government officials may use cases like that of R-A- or N-S- as evidence of progress, but these cases remind me that the U.S. gets let off the hook. The U.S. seems like the “nice guy” or the “white knight” stepping in to help the female victim from the impoverished country. But, is the U.S. really a safe place for women? The juxtaposition of the cultural issues of “Third World” or “developing” countries with the safe haven provided by the U.S. as a “First World” or “developed” country is both factually inaccurate and politically problematic.

Suggested Readings:

Musalo, Karen. 2010. “A Short History of Gender Asylum in the United States: Resistance and Ambivalence May Very Slowly Be Inching Towards Recognition of Women’s Claims.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 29(2): 47-63.

Oxford, Connie. 2005. “Protectors and Victims in the Gender Regime of Asylum.” NWSA Journal 17(3): 19-38.

1475-6781/asset/JSS.gif?v=1&s=377bb8e0c3d0fcf201f301ded7cf610142072c3e)

1467-7660/asset/DECH_right.gif?v=1&s=a8dee74c7ae152de95ab4f33ecaa1a00526b2bd2)