Yes, You Are a Statistic

I can no longer stomach certain clichés. Last night at the Democratic National Convention, I heard one of these. A university student, who introduced Dr. Jill Biden, wife of the Vice-President, noted that she “shouldn’t be here” and was “almost a statistic.” My immediate response, to my computer screen, was “You still are a statistic and you don’t understand what statistics are.” I know that she was just rehashing a cliché, but it is a cliché that privileges “self-help culture” and undermines social science.

I can no longer stomach certain clichés. Last night at the Democratic National Convention, I heard one of these. A university student, who introduced Dr. Jill Biden, wife of the Vice-President, noted that she “shouldn’t be here” and was “almost a statistic.” My immediate response, to my computer screen, was “You still are a statistic and you don’t understand what statistics are.” I know that she was just rehashing a cliché, but it is a cliché that privileges “self-help culture” and undermines social science.

To be fair, by this point I had listened to a number of speakers say little to nothing of substance for over an hour and was not in the best of moods. Still, the defiant tone of “I didn’t want to be a statistic” and “I shouldn’t be here” treat social statistics (not the social reality but the reporting of such statistics) as some form of oppression from which she, with the help of Dr. Biden, freed herself.

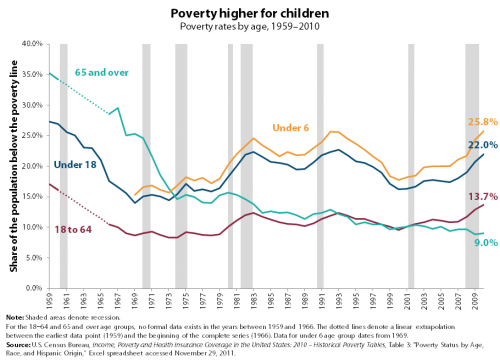

First, statistics, like the ones in the charts in this post, are based on reality. Scientists do not conjure them up to demotivate people like the principal in Back to the Future telling Marty McFly that he will never amount to anything and shouldn’t try. Secondly, we are all statistics. You, me, everyone. Statistics about people are based on people. If a report notes that 53% of students from some town drop out of high school, the other 47% are still part of the statistic. I could just as easily say, 47% of students graduate high school. I realize I’m being excessively sarcastic about this point but that we are all implicated in statistics speaks to why they matter.

The 47% who graduate, in my example, have not opted out of that system, or defied the statistic. They are part of that statistic and their lives, while, of course, more complicated than membership in one of the two groups the statistic defines, will be influenced by the social realities that such a statistic illuminates. For example, a student from such a town will likely have less friends going to college and will have less information about the college application process. The college-bound student from that town will also likely have to leave friends behind.

Now, I understand that part of what someone means when they say they weren’t a statistic is that “the odds were long but I succeeded – so I am exceptional.” But self-congratulations were not what most speakers at the DNC alluded to when they spoke of their humble beginnings. Instead, they talked about the greatest of America and its opportunities. Of course, they are aware that not everyone from such humble beginnings landed where they have and that there were some problems with the opportunity structure, even in whatever “golden age” politicians hope we conjure up.

President Obama, and others, touched on this when they said some variation of “We don’t expect government to do everything, but our society should give everyone a fair chance.”

I disagree.

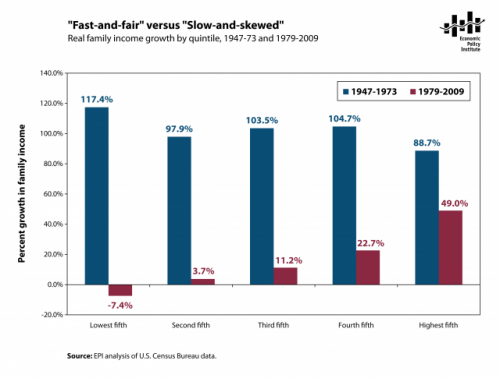

Government policies determine not just the fairness of “the game” but where “winners” and “losers” end up. Consider the classic board game Monopoly. In the game, everyone begins with the same resources and throughout the game everyone plays by the same rules. The game ends when one player has all the money and everyone else is bankrupt. This is not the kind of society anyone wants.

The fairness of thus game, however, is irrelevant to the undesirable outcome. Similarly, the structure of our society, while vastly more complex, conditions the level of inequality. The level of inequality is alterable, but not through individual action. This basic truth is missing from the self-help literature that inspirational stories of overcoming adversity often mimic.

McGee (2012) notes that, self-help culture is, “among the means by which advanced capitalist societies govern their subjects.” Self-help culture helps people ignore how the game might be rigged, while allowing organized elites to continue rigging the game against unorganized masses. But, perhaps more importantly, the inward focus of self-help culture dissuades people from channeling “the desire for a better life into social action that resonates beyond the boundaries of a neoliberal conception of an autonomous individual self.” Self-help severs the desire for a better life from social action because self-help encourages people to imagine themselves as autonomous or disconnected from the social, political, and economic contexts in which we live. The disengagement from politics that leads at least 1/3 of the electorate to not vote likely stems from the belief that politics “doesn’t affect me.” Does self-help culture and the closely related statistic-defying sentiments add to this attitude? I wonder how much self-help culture might stunt our democracy.

Further Reading:

All charts from the Economic Policy Institute athttp://stateofworkingamerica.org/

Very nice article! You can find more information about applied stats in this website: leocremonezi.com

Hope you enjoy it.