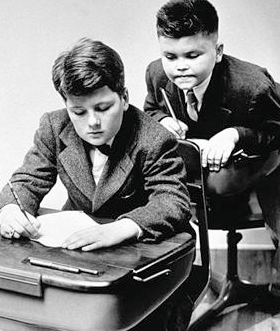

Is THAT Cheating?

Last week, a survey of 1,300 incoming freshman at Harvard University found that 42 percent of respondents had cheated on a homework assignment or problem set before starting at Harvard. This study lead to countless editorial pieces with provocative titles such as “Welcome to Harvard, Cheaters of 2017” and “More Incoming Harvard Students Have Cheated On Their Homework Than Had Sex.” However, what the study and related articles did not discuss was how “cheating” was defined both for those conducting the survey and those responding; how technology has complicated the definition of “cheating;” and if academic institutions as well as the larger social structure needs to rethink academic ethics in today’s changing and advancing digital society.

Survey data is one of the most widely used tools for empirical investigations of the social world (Glock 1967). It is the best method for collecting data on a population that is difficult to observe (Babbie 2013). And because survey methods can be less time consuming and cost prohibitive for collecting descriptive data, it has become increasingly popular among small newspapers, magazines, and media organizations.

However, like any research method, surveys have strengths and weaknesses. Researchers and respondents need to have carefully constructed instruments, using clear terminology so both respondents and researchers associate specific terms with the same meanings. This can be a challenge when trying to understand phenomenon that have varied and complex meanings. “Cheating” is an exemplar of this kind of complex social phenomenon.

Many people have diverse notions of what constitutes cheating and most people believe there are degrees of cheating, which correspond with various levels of seriousness. In a 2006 study of student attitudes about cheating with information technology, participating college students rated activities such as purchasing a paper as a “quite serious form of academic dishonesty,” while submitting a paper used in another class was only rated as “somewhat serious form of academic dishonesty” (Etter, Cramer, & Finn 2006).

Molnar, Kletke, and Chongwatpol also found that undergraduate respondents had a different ethical standard when IT was involved (2008:666). For example, stealing a software package from a store was considered a serious offence, while illegally downloading the same package from the internet was considered minimally unethical. Gail Wood suggests students’ views about cheating and plagiarism are the result of being raised on media and internet content that is often not cited according to scholarly standards (2004:238).

Advances in information technology have clearly complicated issues of academic integrity on college campuses. As technology continues to progress, universities need to reexamine academic ethics in today’s digital society. McCabe and Pavela suggest that in addition to affirming the importance of academic integrity and clarifying expectations for students, professors need to develop fair and relevant forms of assessment (2007). For many people, that means redefining “cheating” within the context of a society where information is accessible at the click of a mouse and shared between users in a fraction of a second.

Further Reading:

1468-0491/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=859caf337f44d9bf73120debe8a7ad67751a0209)