"Who Are you Calling Entitled?" : The Problem with Lazy Millennials

In a recent Sociology Compass article, Dr Elisabeth Kelan draws attention to common uses of the concept of ‘Generations’ and points out that despite being a useful and commonly used concept for Psychology, it has not been widely drawn upon in the Sociological literature. This is surprising, as she notes, because it is so often used in more mainstream writing, media and culture, particularly to describe the characteristics of certain demographics of people. In reference to Dr Kelan’s work, the concept of generation can provide insight into how organizations can best treat their employees, by using their generation as a lens to understand their motivations, preferences and behaviors. Knowing what generation someone is in can be extremely helpful for our understandings of how people behave in certain ways.

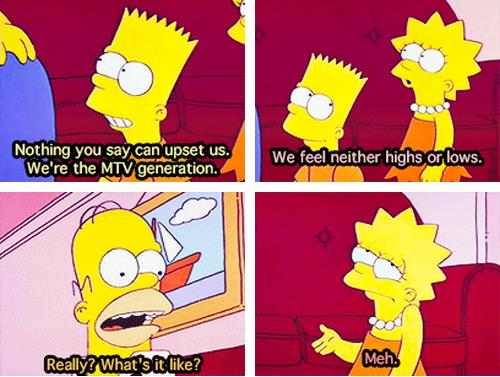

This is because, as in The Simpsons quote in the picture above, generations are often assumed to have certain characteristics or personality traits. ‘The Baby Boomers’, ‘Generation X’ and ‘Generation Y; (or ‘Millenials’) are terms we adopt fairly easily and they have a certain cultural currency. This may be because they lived through key events (World Wars, 9/11, Depression, etc.), or because of changing social norms and cultures, but they are often assumed to hold similar values and beliefs as a result. Whereas it may be more fluid and less easy to criticise or assume things about someone based on their age, and stereotypes based on race, religion and gender are less appropriate (although, unfortunately, still common), as a society we are comfortable with generational traits. It is a common habit we have of comparing our own generations to those before or after us.

Recent research by Paul Harvey does just this. He argues that Generation Y (the Millennials – born ~1980-2000) are a generation of ‘entitlement-minded workers’ : partly due to a praise-based method of parenting style that was popular in the 1970s and 1980s our generation has been raised with unrealistic expectations about what we can achieve. We also tend to be praise and reward-driven, rather than simply by the desire to work. We are therefore, seen as ‘bad employees’; this sense of entitlement and resistance to negative feedback makes us difficult to employ and manage. Our generation has, according to the authors, “been led to believe, perhaps through overzealous self-esteem building exercises in their youth, that they are somehow special, but often lack any real justification for this belief”.

As a Millennial myself, I found it difficult to read this without feeling both offended and defensive. Our generation are the first that do not expect to earn more than their parents, and are unlikely to (unless we are already part of the rich elite, in which case our relative wealth will continue to increase). We accept risk as part of our continuous life journey, we do not expect financial stability or job stability, because neither is common any more. More of us than ever will graduate from university, starting our working lives more in debt than any generation before us, (thanks to being lied to by a government that committed to not raising tuition fees), in a world where we are also expected to work for free, for longer than ever before. We are the post-AIDS crisis generation; where the Baby Boomers has the 1960s and 70s and increased permissiveness towards sex, ours remains stuck in a paradox between an increasing sexualised culture, with the hangover of risk and fear, particularly towards women’s sexuality. And just when you thought it couldn’t get any better, we’re being labelled as lazy and entitled by the very generation who have the power and money to employ us.

I know, I know, I need to stop ranting. Maybe I’m just in a bad mood because of my entitlement-minded approach to work, or my need for constant praise, but I can’t help but feel there is a tendency for any generation to criticise the generation below them, particularly for being ‘lazy’, or taking things for granted. My point is not to criticise the use of these stereotypes per say, more that better and more rigorous research needs to be done to examine where they come from and what other factors may be affecting these traits. Most crucially from a sociological perspective, it is not easy to operationalise the differences between generational effects and those related to age. Research like Harvey’s that doesn’t utilise a comparison group, doesn’t account for changes in society and doesn’t control for the characteristics of youth simply perpetuates stereotypes without critically engaging with them.

Returning to Dr Kelan’s work, her research into the experiences of Milennals in the workplace is a far more nuanced examination of the intersection of age, generation and other demographics. By utilising a feminist and intersectional perspective she outlines the positives of generational differences too, and how they can be harnessed for better organisational effectiveness. As with gender, age, ethnicity, race, religion and disability, there needs to be better provision for people across the spectrum of these demographics, and less time spent stereotyping. Or maybe I just want more praise and entitlement?

1475-682X/asset/akdkey.jpg?v=1&s=eef6c6a27a6d15977bc8f9cc0c7bc7fbe54a32de)

1540-6210/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=812a48e1b22880cc84f94f210b57b44da3ec16f9)

Frustrating