The Marathon and Gender Equality

By Richard Smith from Bowen Island, Canada (Chicago Marathon – the start) [CC-BY-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Last week marked the first installment of the Boston Marathon after the horrible terrorist acts of 2013. Although the world-renowned event will forever be linked to these atrocities, there are also acts of positive social change linked to its. Most famously, the 1967 Boston Marathon saw Kathrine Switzer become the first woman to enter the race as a numbered runner (there had actually been other women run the race unofficially before) by registering as “KV Switzer”. Her run and the attempt by a race official to remove her from the race show how sports can become an arena of progressive social change. Moreover, the history of marathon running over the past half century can also serve as a teaching tool to challenge myths about the supposed fundamental differences between men and women.

The world famous images of Kathrine Switzer running in the Boston Marathon have become a symbol for women’s struggle against patriarchy in the 20th century. The Boston Marathon had been – and officially remained for another 5 years – an exclusively male space, with women barred from official contention until 1972. That women were just not fit to compete in this type of event was one of the justifications given for their exclusion. Nevertheless, Switzer registered for the race in 1967 by providing her initials rather than her first name on the registration forms.

The images of Switzer being attacked by a race official can be seen as encapsulating the fight for women’s equality and the possibility for social change. The individual in the black clothes, race official Jock Semple, upon realizing a woman had entered the race as a numbered contestant, charged at her and attempted to rip the numbers of her clothes. In many ways, Semple thus can be seen as exemplifying the structural barriers holding women back as well as those (men) literally prepared to fight to keep them out. At the same time, though, the images also convey the importance and power of allies: The man in shorts, Switzer’s boyfriend, reacted to the situation by body-checking Semple, thus ending his attempt to enforce the status quo. For Switzer’s attempt to run the Boston Marathon to be successful, it did not only take her courage to enter and her endurance to complete the race but also the – quite literal – fight by her and her allies against institutional barriers and their real life enforcers.

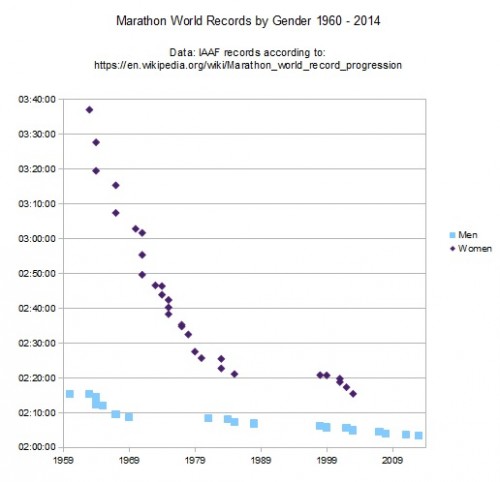

In addition to showing social change in action, the images of Switzer running and ultimately completing the marathon also imply sociologically valuable lessons about difference and inequality: While race officials would have argued that women were incapable of running the marathon because of their different (and inferior) athletic skills, the reality has been that exclusion and inequality are the factors that prevent women from realizing their athletic potentials. That it is inequality that creates difference, rather than vice versa, can be seen by looking at the marathon world records for men and women between 1960 and today:

Prior to the 1960s, the marathon had been virtually exclusively male, with no official competitions for women. Once women begin to compete in the race, the difference between the men’s and the women’s world record is more than 1h 15mins. For conservative race officials and sports commentators, looking at this data point alone might have confirmed their suspicion: Women seemed to be inherently different to men when in came to their sporting ability; the best woman needed more than 1.5 times the amount of time to complete the race than the fastest man. However, this gap between the men’s and the women’s world record narrowed rapidly over the next 30 years or so, and by the mid 1980s had closed to about 15 minutes. Today, the women’s world record is a mere 12 minutes slower than the men’s, and virtually on par with men’s world records from the 1960s. Rather than women being fundamentally different from men, it is exclusion and lack of opportunity that created the appearance of fundamental differences.

Additionally, marathon results also exemplify perfectly the need to reject binary conceptions of gender and to argue for gender as a continuum. Often we hear the argument that men are inherently stronger/ faster/ more athletic than women, implying the idea that this is true for many if not all individuals, or, at the very least, creating arguments based on averages to then be applied in everyday situation. However, in reality these averages mean very little. While the statement “men are faster marathon runners than women” may be true in terms of the fastest time, and possibly even average times, it tells us nothing about any individual man or woman. For instance, even when looking at the top runners in the world, the results are not as gender-segregated as the statement “men are faster than women” makes it out to be. Looking at the 2014 results of the Boston Marathon, one of the most prestigious races in the world, reveals the following: While the winning time for men was 2:08:37 (Meb Keflezighi), the winning woman – Rita Jeptoo, crossed the finish line in 2:18:57, a little more than 10 minutes later. What is more, Jeptoo came in 21st overall, and a total of four women can be found amongst the top 30 runners. In other words, in the 2014 Boston Marathon there were a mere 20 men for whom the statement “men are faster than women” is true. In contrast, Rita Jeptoo actually finished ahead of about 17,500 men.

1520-6688/asset/Capture.jpg?v=1&s=b5076c49a7d1c5f1b9cf0dd9cd292394a3be81cc)

1 Response

[…] [This article first appeared at SociologyLens] […]