Men's Room: why space is a feminist issue

I am lucky, (if you can call it that, as I am fairly sure I can claim some credit for its creation) to spend most of my life surrounded by feminist men. I was raised by one, and have friends, lovers and colleagues who are very happy identifying as (male) feminists. They can deconstruct the patriarchy, discuss oppression and understand intersectionality. They constantly and consistently ‘check their privilege’. And maybe this is why a recent article; ‘20 tools for men to further feminist revolution’ struck such a chord with me. It is written from one male feminist to the rest, pointing out that it is not enough simply just to identify as being feminist. Fighting patriarchy, (whatever your sex or gender) cannot be done apathetically or without actually doing anything.

I am lucky, (if you can call it that, as I am fairly sure I can claim some credit for its creation) to spend most of my life surrounded by feminist men. I was raised by one, and have friends, lovers and colleagues who are very happy identifying as (male) feminists. They can deconstruct the patriarchy, discuss oppression and understand intersectionality. They constantly and consistently ‘check their privilege’. And maybe this is why a recent article; ‘20 tools for men to further feminist revolution’ struck such a chord with me. It is written from one male feminist to the rest, pointing out that it is not enough simply just to identify as being feminist. Fighting patriarchy, (whatever your sex or gender) cannot be done apathetically or without actually doing anything.

In follow up to this (and in a slight criticism of the first article’s academic tone), another author on the website xojane.com offered practical suggestions for applying the theoretical perspectives offered by the “20 tools”. The practical suggestions range in their scope and intended outcomes, but all are simple and effective ways men can (relatively) easily, quietly and occasionally enthusiastically, help to support the feminist cause without dominating the discussion. This last bit is really crucial element; even just anecdotally I have lost count of the number of times a male feminist will declare himself as such, only to spend the proceeding hour/day/conference/talk/panel/date/lifetime interrupting (feminist) women and ensuring he is the authoritarian voice. As intersectional speakers have been arguing for years: sometimes being an ally means knowing when to simply shut up and listen.

The list of course, isn’t perfect. As with any list-based article (that seem to have become prevalent to the point of saturation in recent years) they have a tendency to oversimplify complicated notions of oppression and power dynamics in order to make them more appealing and accessible to a wider audience. There are also some that I vehemently disagree with: for example where the author argues that men should pay for condoms, to acknowledge that “they will not have to deal with the problem of pregnancy”, and “because men earn more than women”*. I do however want to pick up on one of the advice points that is really important, I find, both as a woman and a sociologist.

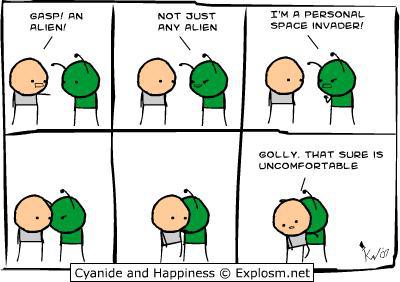

“Give women space: Many women walk around — especially at night or while alone — feeling on edge and unsafe. Being in close physical proximity to an unknown man can exacerbate this feeling. Recognize that this is not an unreasonable fear for women to have, given how many of us have experienced harassment or abuse or been made to feel unsafe by men when we are in public spaces. Also recognize that it doesn’t matter if you are the kind of man who a woman has any actual reason to fear, because a woman on the street doesn’t have a way of knowing this about you or not.”

This point highlights so clearly the experience of being a woman, and the convinction and assumption that you and your body may be in danger. This is often where even the most feminist men find it difficult to empathise. Walking down a dark street at night, a man may be wary of potential dangers, but they are unlikely to have the same level of concern when in daylight, or in a ‘safe’ environment. For women, rape culture means any situation is assumed to be potentially dangerous. Your body gives you away as female and therefore as potentially a ‘victim’.

When I discussed this issue with a gay, male (feminist) friend of mine, he talked about coming to this realisation: He is used to spending his time being viewed as distinctly ‘unthreatening’ by his female friends, and used to us trusting him because we have no reason not to. It was only after a number of events where he noticed women avoiding walking on the same side of the street as him at night, or avoiding the top deck of a night bus when he was there (a commonly observed ‘girl’ rule) that he realised it: to female strangers he was being defined as a potential threat. As above; “it doesn’t matter if you are the kind of man who a woman has any actual reason to fear, because a woman on the street doesn’t have a way of knowing this about you or not.”

Space is a feminist issue. The body is a feminist issue. Iris Marion Young, in her seminal essay ‘Throwing Like a Girl’: argues this perfectly – to be ‘feminine’ (and to be female) is to exist in a smaller space, to actively work to take up less room than men. In the tacit and everyday physical movements we undertake, women don’t tend to engage their whole bodies with the same “ease and naturalness” as men. One of the best descriptions I have seen of this comes from a poem called “Shrinking Women” by Lily Myers. She wonders; “if my lineage is one of women shrinking, making space for the entrance of men into their lives?”. Women are taught to accommodate, to shrink, and to create space. Men do not; they are encouraged to spread, to utilize space, to occupy it without question.

As I write this article I am sat at a desk in the university library. While I type, a young male student has come to sit down at the computer next to me, despite the fact that there are plenty of other spaces without anyone near them. He has spread his books out, loudly. He is not embarrassed or ashamed of taking up space in the world, and it hasn’t (I assume) occurred to him that his physical presence is making me uncomfortable. When you are female, your space becomes more precious. The personal space around your body is a cushion and an invisible but highly penetrable forcefield between you and potential threats.

It will require a much bigger cultural shift to change society in a way that doesn’t encourage men to occupy, while women accommodate. But allowing women a physical space simply to exist in without it being encroached upon can make a real difference.

*Quite apart from both of her arguments being distinctly flawed, as a woman I would feel very uncomfortable making a male partner assume financial responsibility for OUR joint decision not to have children anytime we want to have sex. In addition to being reluctant to making it solely his responsibility any more than it is solely mine, making men pay for condoms does not come close to tackling power in (hetero)sexual relationships or the reasons contraceptives are still difficult to broach in conversation with a (new) partner.

Great article. As a self-identified male feminist it’s good to remind oneself of the importance of granting space to women. The Iris Marion Young notion that men like to spread out and women generally feel inclined to ‘shrink’ is a fascinating one, and makes me wonder if that is a natural predisposition or a socialized one.

You should leave your hate filled words somewhere else. They don’t belong in this forum.

It really, really makes my life easier when internet trolls prove the very point I am making, underneath where I make it. Thanks, “fuckyou” (the pseudonym used by the commenter). You’ve been a great help!

(scarlettbrown and Sara’s comments are in reference to a hateful and incendiary comment posted by an anonymous reader that has been deleted)

Why should another person have to be a mind reader because of your internal feelings? Should I also demand that all women stop wearing perfume because it is offensive to my sense of smell? Can I now demand women stop putting on makeup because I dislike the fabricated faces they wear? Where does this ridiculous line of reasoning end?

Hi Richard,

I’m not asking people to be a mindreader, just giving them a bit of a heads up that for women (and some men, i’m sure), getting in my personal space can be very intrusive in a way you might not have thought about.

I don’t wear perfume for exactly that reason, so at least on that one we agree. I don’t know where makeup really comes into that, because I didn’t say anything about disliking anyone’s face. So maybe that’s where the ridiculous line of reasoning ends?