The homeless as the last materialists – an obsession with cash

“Without money, without income, there is no social existence, no existence at all in fact, material or physical. […] The paradox of capitalist societies is that the economy is the main source of exclusion but that this exclusion not only excludes people from the economy, it excludes or threatens ultimately to exclude them from society itself” Godelier, 1998:2[i]

In today’s society, money is the non-plus-ultra. There is no way around it. You use it every day to buy a morning-coffee, pay for a lunch-deal at M&S and the after-work cocktail with your friends. You can’t live without.

But money’s appearance has changed. In the past century, money has increasingly ‘dematerialised’ and ‘virtualised’[ii] – just think about Bitcoins. Money was a tangible commodity when we still had coins; how wonderful to feel the heaviness of a piece of silver! Already in its paper form, representation and sign became more important.[iii] Now, even this ‘fake materiality’ is lost as money appears more and more with a virtual face.[iv]

Ask yourself: how often do you use hard cash? How many times in comparison do you put your debit card into a card reader, quietly insert your pin and wait for the receipt to print?

We don’t really see money anymore; we are – in this respect – losing our materiality historically so often linked to a feeling of security, power and dominance. A silver-clip full of dollar notes is not doing it anymore. The new epitome of modern wealth are platinum and black credit cards.

This dematerialised form of money is, however, still dominant in particular parts of society. The biggest sector still completely dependent on cash is the informal or illegal economy. It is hard to pay for drugs with a platinum credit card; neither you nor your dealer want to be traceable. But another group – a little less loaded, but a little more visible at least for urban dwellers – uses cash and cash: people who are homeless and beg. They are what I want to call the ‘last materialists’.

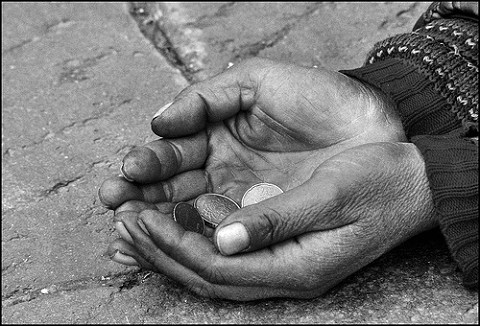

Most gifts to people on the street are cash and thus material, tangible. It is the copper and silver coins in particular that people like to give – because the denominations are so small that it almost feels too much effort to carry them around and wait for the possibility to use them. People give them away – even to strangers sitting on pavements.

The materiality for the street person doesn’t end with the moment of the donation, however. During the months of my fieldwork on the streets of London I observed all kinds of actual engagement with the money. Many people very carefully choose for instance which coins to leave in the cup. Most pound-coins are taken out immediately: one wants to appear needy. Others like to look at the coins and polish them before they put them away. Different coins are also often separated into different pockets – with the higher denominations closer to the body. All of the people I spoke to, however, knew exactly how much money they had in their pockets at any one time. They constantly keep track.

These observations do not only tell us something about the receivers, the people who beg. With the advent of its immaterial form, do many people value cash less and hence lost grip of their debts? Are we increasingly literally ‘loosing touch’ with reality? Everything seems only a contactless payment away. Already twenty years ago, it was becoming increasingly clear that virtual money is easier to spend.[v] Debt crisis after debt crisis is what we got afterwards – partly because we are not ‘materialist’ anymore.

Street people on the other hand are materialists. Not out of their own choice, however. The person who begs is often not able to participate in the immaterial circuit. Many street people don’t have bank accounts at all and surely no debit or credit card. Even though it might be good to be a little more of a money-materialist than many members of the general public are, if the use of cash-only is forced, something else goes terribly wrong.

[i] Godelier, M., 1998. The Enigma of the Gift, Cambridge: Polity Press.

[ii] Leyshon, A. & Thrift, N., 1997. Money/Space: Geographies of Monetary Transformation, London: Routledge, p.22

[iii] Baudrillard, J., 2007. Symbolic Exchange and Death, London: Sage.; Rotman, B., 1987. Signifying Nothing: The Semiotics of Zero, London: Macmillan.; Shell, M., 1995. Art and Money, University of Chicago Press.

[iv] Galbraith, J.K., 1978. Money, Whence It Came, Where It Went, London: Andre Deutsch.; Gilbert, E., 2005. Common cents: situating money in time and place. Economy and Society, 34(3), pp.357–388.

[v] Ritzer, G., 1995. Expressing America: A Critique of the Global Credit Card Society, Newbury Park: Pine Forge Press.