In the Company of Spectacle Makers

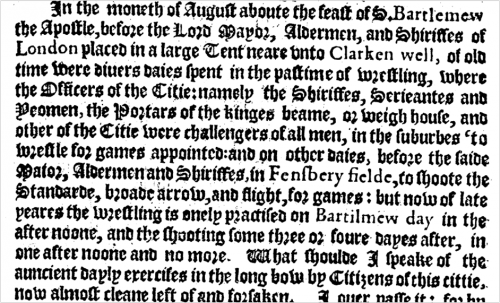

Something rather curious is going to happen next week. On Michaelmas – the 29th of September – the next Lord Mayor of London will be elected by the Liverymen of the City of London’s trade associations – those gilded ‘Worshipful Companies’ of, among other craftsmen, the Goldsmiths, Spectacle-Makers and even Management Consultants. (The Lord Mayor presides over the City of London – the Square Mile on the north bank of the Thames that historically has been home to London’s financial centre – and is not to be confused with the Mayor of London, who runs the Greater London Authority.) Shortly after election, the new Lord Mayor travels, in the State Coach, to swear allegiance to the Crown, amidst the pageantry of the Lord Mayor’s Show. One could be forgiven, perhaps, for thinking of the Show as ‘mere’ ceremony, devoid of the unmistakable and overt political functions – including competitive displays of power, and surveillance of the City’s inhabitants – that was enabled by its Medieval predecessor, the now defunct Midsummer Watch (described by John Stow in his 1598 Survay of London, above).

It is, as the anthropologist Webb Keane might suggest, only a self-consciously ‘modern’ – perhaps distinctively Post-Reformation – stance towards the world (what Keane calls a ‘semiotic ideology’) that allows ceremony, spectacle and pageantry to be seen as a distraction from ‘real’ politics. For the thoroughly modern amongst us, real politics should take place in a realm of propositions and counter-propositions, to be assessed on their truth value alone, with no regard to the medium through which we encounter them. Of course, a desire to view ourselves as semiotically modern, and immune to possession by ‘mere’ ceremony, does not preclude the possibility of political battles being fought ‘on the terrain of media spectacle,’ as Douglas Kellner suggests they are and will be. (And, as the anthropologist Emma Crewe has shown, ritual and ceremony is at the very heart of British parliamentary politics.) Perhaps, then, the extent to which the Lord Mayor’s Show – along with the pageantry of the Livery Companies and the City’s Guildhall – is sometimes received by the viewing public as somehow being ‘outside’ real politics, might have something to do with the way we have grown accustomed to experiencing museums.

The folklorist and museologist Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett has documented the metamorphosis of museums during the twentieth-century. Starting off as exciting spaces central to the new sciences of exploration and collection (from geology and botany to ‘ethnology’), museums declined after the Second World War. The natural sciences moved into university laboratories, and the social sciences became more than a little embarrassed about the museum’s role as the ‘final resting place for evidence of the success of missionizing and colonizing efforts.’ So, the solution became clear: produce some heritage! Anthropologists would suggest that you also need to take a self-consciously ‘modern’ stance in order to conceive of heritage (or indeed, authenticity) as a value. This is because the basis of heritage production is adding value based on ‘pastness’ – to living persons, practices and artefacts. Think of Japan’s Living National Treasures, or even the rise of heritage and heirloom seed-saving. One of the side-effects of our becoming accustomed to these successive genres of display is perhaps that ceremonial paraphernalia like the Lord Mayor’s Coach – known by most visitors to the City as an artefact in the Museum of London – comes to be valued in the present for its ‘pastness’, and loses any association with real, significant and ongoing exercise of power by the Lord Mayor and the City Corporation.

But, you may ask, does the office of the Lord Mayor in fact exercise any significant power? If you were to go on the Occupy London Tour of the Square Mile, you might come away feeling that it most certainly does. And for journalist Nicholas Shaxson, the fact that the Queen cannot enter the Square Mile without gaining the Lord Mayor’s permission reflects its status as an ‘offshore’ tax island whose very real authority Parliamentarians seem more than a little afraid to encroach upon – a few abortive and occasionally underhand attempts notwithstanding. (The more conspiratorial among the readers might suspect this has something to do with the City’s own lobbyist having a right of access to the ‘Under Gallery’ in the House of Commons.) But, perhaps even more worthy of our sociological attention, the Lord Mayor is able to claim (as she did at a ‘science and capital’ event I attended in the Guildhall earlier this year), that the City is the world’s ‘oldest civil democracy,’ which, as one globetrotting economist in attendance put it, ‘has a centuries old tradition as we know of doing right and brilliant things.’ True enough, the City has acted as a restraint upon despotic sovereigns, and formed a template for modern municipal government in England. But the format of its elections – not only of the Lord Mayor, but of the Common Councilmen elected annually in March – reveal a rather troubling history undergirding this putative oldest of civil democracies.

The historian Peter Claus recounts how, during the 1840s, a time of great upheaval in the City, advocates of citizenship and voting rights for all who were resident (such as Joshua Toulmin Smith) lost out to those who advocated voting rights for property owners alone. The contemporary transformation of this legacy, as Shaxson and the City Reform Group – a curious collection of campaigners of every conceivable political stripe – are keen to point out, is that since 2002, along with City residents, businesses are able to vote (with one vote available for every five employees). Perhaps this bizarre electoral system does not trouble the City’s claim to being the world’s ‘oldest civil democracy’ because of the pageantry, spectacle and sumptuous display that signal a tame ‘heritage’ organisation, to be valued precisely because it is passé? Sure enough, as Michael Pryke has shown, the City is not what it used to be, and the Bank of England is no longer able to tightly control its spatial and social boundaries. But as financial industries become more ‘deterritorialized’, the City has become ever more conscious of what Anna Minton calls ‘Ground Control’: the privatisation of ostensibly public space. It is hard not to wonder whether this has anything to do with a City Corporation that owns 20 percent of City land, and whose venerable democratic history evinces more than a little bias towards the propertied classes.

1099-0860/asset/NCB_logo.gif?v=1&s=40edfd0d901b2daf894ae7a3b2371eabd628edef)

1540-6210/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=812a48e1b22880cc84f94f210b57b44da3ec16f9)