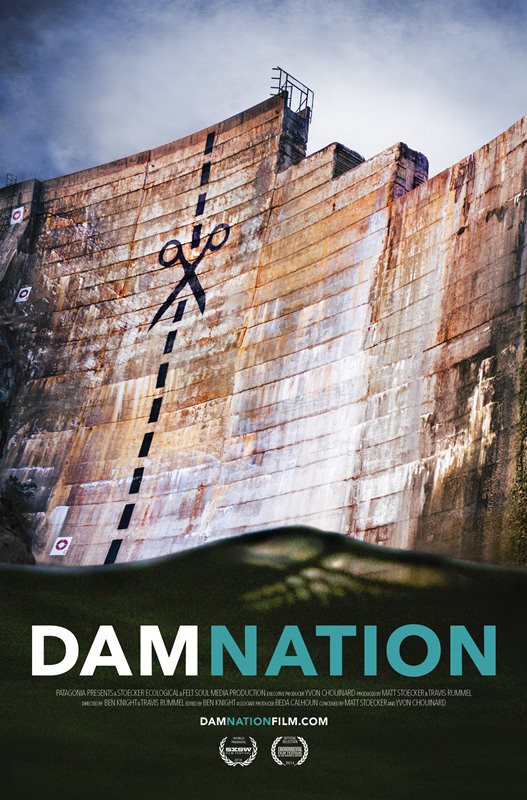

Dam-nation, Dissent and Cognitive Dissonance

Official movie poster for ‘Damnation’ depicting a real piece of graffiti on the Matilija Dam, painted in 2011.

I just got back from IDFA, the International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam, where I volunteered in the running of this annual two-week event, in exchange for the chance to gorge myself on a host of documentary films, gratis. Lots of different subject matters were covered: graffiti artists in Brazil, al-Shabab militants in Somalia, music therapists in the United States, arms dealers in India, fracking in South Africa, loads of stuff. Not only were most of the films extremely watchable and enjoyable – despite often being about quite depressing, gritty topics – but it gave me lots of material to blog about (watch this space), and has even made me consider whether my PhD research could possibly form the basis of my own documentary – one can but dream!

One stand-out documentary was DamNation, the story of American environmental activists fighting for the removal of some of the tens of thousands of dams which cross United States’ rivers. This huge dam network is harming eco-systems and fish-stocks, particularly the migration routes of salmon in Washington and Oregon states, whilst providing negligible benefits in terms of jobs or hydro-electricity generation. Many of these dams were built to feed a construction-job-creation spree in the 1930s-1950s but are now serving little purpose. In many cases the dams are depriving beaches downstream of sand and silt, and increasing flood risks as well.

DamNation’s story had a more optimistic tone than some of the other docs I saw, because it is, partially, a success story: many of these old dams are actually being decommissioned by the US authorities who recognise that they are an economically obsolete blight on the natural beauty of America’s great rivers, and their usefulness has in many cases long run its course. The anti-dam protestors come in all shapes and sizes, from ‘moderate’ local farmers and fishermen to die-hard Earth First! activists such as Mikal Jakubal, the courageous/insane man who used ropes, paint, skill and bravery to create striking and iconic pieces of protest art, like this:

This piece of protest art was created in 1987 on the Glines dam crossing the Elwha River. In 2011 the dam was actually removed by the authorities. Picture courtesy of Mikal Jakubal taken from http://www.seattlemet.com/travel-and-outdoors/olympic-national-park/articles/elwha-river-dam-august-2011

Such high-wire direct action invokes the spirit of Edward Abbey, author of the ‘Monkey Wrench Gang’. This seminal novel, published in 1975, tells the fictional tale of a group of idealistic eco-warriors who sabotage mines, dams, power stations and infrastructure projects across the USA to preserve the country’s natural beauty against the tide of industrial capitalism, and in doing so, Abbey created a blueprint for Earth First! and other radical environmentalists. One of Abbey’s many memorable quotes is used in the film: “Sentiment without action is the ruin of the soul.” That is: thinking one way is not enough, we have to act in line with our convictions lest our sense of satisfaction with our life and lifestyle, our self-image, our ‘soul’ becomes degraded and sullied. Just feeling angry about the destruction of nature (or any other issue, for that matter) is not enough. If we don’t follow our feelings with actions then we are letting ourselves down.

Book cover of The Monkey Wrench Gang, by Edward Abbey, Dream Garden Press hardcover.

This line stayed with me for days after I saw the film, because it echoes a concept I keep coming across again and again in my research on behaviour change: cognitive dissonance. This is the social psychologist Leon Festinger’s idea that all humans seek harmony between our actions and our beliefs. When our actions and beliefs don’t agree with each other, we soon become uncomfortable. A strict observer of a religion will want to observe the rituals of that religion; a vegetarian will never want to eat meat. If, for some reason, such as being in an unusual place away from home, it is not possible to act in consistency with those beliefs, we don’t like it. We hate it. Just ask a vegetarian who has to eat meat in a restaurant because they can’t speak the local language, or ask the muslim prisoners at Guantanamo Bay who were force-fed during Ramadan.

Cognitive dissonance is unpleasant and we always try to avoid it. All of this is perhaps obvious enough. But the interesting thing about cognitive dissonance is that, when we are faced with the possibility of inconsistency between what we think and what we do (and when, unlike those two examples, we have an active choice to make), we usually change our beliefs rather than our actions, a point commonly made by behavioural economists such as Kahneman, Thaler and Sunstein. Understanding this is very helpful when it comes to understanding why so many people say they care about the environment, yet act in ways which contradict this. For example, if a person who claims to be ‘green’ and is a car owner is told that to be ‘green’ means not owning a car, they are, according to Festinger, likely to use one of four techniques to reduce cognitive dissonance:

- Change behaviour or cognition (“I will sell my car”)

- Justify behaviour or cognition by changing the conflicting cognition (“I’m allowed to drive but only at weekends”)

- Justify behaviour or cognition by adding new cognitions (“I’ll keep the car but take one less flight per year to make up for it”)

- Ignore or deny any information that conflicts with existing beliefs (“Cars don’t really make a difference to the environment”)

Options 2, 3 or 4 are mostly likely for most people, because basically, we are extremely good at making excuses so that we can continue our lifestyles and just change the accompanying beliefs instead. Convenient isn’t it. On a policy level it gets more interesting and more worrying, as people’s levels of acceptance of scientific ‘truths’ can be influenced by the perceived consequences in terms of actions. An interesting recent study at Duke University found that when participants were told that tackling climate change would involve more taxes and government regulations, they were less inclined to believe climate change is an existing problem and global temperatures are rising. When they were told that tackling climate change would involve minimal regulation and people could probably continue to behave as before, participants were more inclined to believe climate change is an existing problem and global temperatures are rising. The researchers also noted that Republicans were particularly less likely to believe climate change was a problem if they were told that tackling it would mean more government regulation.

“We should not just view some people or group as anti-science, anti-fact or hyper-scared of any problems,” co-author of the study, Aaron Kay said. “Instead, we should understand that certain problems have particular solutions that threaten some people and groups more than others. When we realize this, we understand those who deny the problem more and we improve our ability to better communicate with them.”

Here we can see the full spectrum of cognitive dissonance as a phenomenon with political, social and psychological implications. At one end, we need to understand that people are extremely skilled at manipulating their own version of reality to justify their actions (or inaction). Realising this poses profound challenges for policymakers, academics or activists who want to change how people behave.

At the other end and on a more individual note, we should remember that the most satisfying things in life are when we act in complete harmony with what we believe. Avoiding cognitive dissonance by adapting our actions rather than our beliefs is often extremely difficult but it makes us feel purposeful and consistent – we are avoiding hypocrisy. This might be one reason why religious people are happier than non-religious people: that they manage to close this attitude-behaviour gap. I’m not sure. But when maintaining harmony between sentiment and action involves making sacrifices or overcoming challenges – whether that be changing what we eat, selling our car or throwing ourselves off a 430-foot dam – perhaps life is a little bit sweeter. @RogerTyersUK

1530-2415/asset/SPSSI_logo_small.jpg?v=1&s=703d32c0889a30426e5264b94ce9ad387c90c2e0)

Cool. Here’s my song on exactly this issue:

http://youtu.be/bOiQfR1kOKY

Let’s Just Get The Shopping In.

I’ve never known whether to be proud of it for feeling I’ve communicated ‘something’ comprehensive, or ashamed enough to bury it forever. It’s all so overwhelming, any further conclusion seems insane.

I have a new piece of stage banter, now I know what the phrase means: this is my cognitive dissonance song.