‘Fair Play’ & the ‘Level Playing Field’? Gender & Spectacle at the Olympics

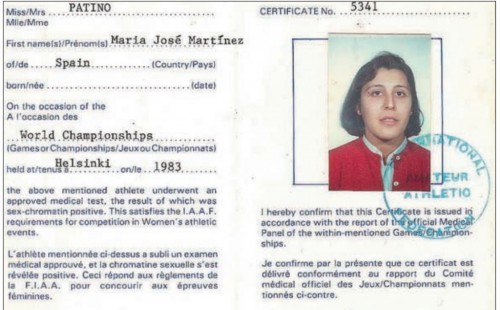

Gender certification for María José Martínez-Patiño, a victim of the chromosomal testing era. Via http://transascity.org/cross-training-the-history-and-future-of-transgender-and-intersex-athletes-3/

It is hard to disavow the wonder and enchantment that watching the Olympics engenders. It’s easy to become engrossed by the spectacle of elite athletes pursuing seemingly impossible, barely perceptible improvements in sports that, for the next four years, you may never again consider. And spectacle is precisely what the Olympics proffer. But as Michael Silk (2011) writes in Sociology, the spectacle of sporting mega-events does far more than merely enchant. In London 2012, sporting spectacle was put to work as a tool for negotiating Britishness ‘after Empire’, sidestepping unexamined fault lines of race, class and nation. Silk describes the nation branding strategy developed in the run-up to the Olympics, designed to present ‘Brand Britain’ as ‘Timeless, Dynamic and Genuine’: the University Boat Race and Gothic churches that populated T.S. Eliot’s image of ‘Timeless’ British culture, so beloved of the New Right, were here wedded to the entrepreneurial dynamism of Richard Branson, London Fashion Week, and Notting Hill Carnival (the latter’s history as a site of ‘bitter confrontations’ between blacks and the police duly excised). Meanwhile, as Paul Watt (2013) notes, young residents occupying marginal housing in East London felt confident that Olympic-led regeneration and redevelopment was simply not for them; the photo journals they created with Watt document the building of exclusive, luxury flats, from which they knew they would derive no benefit. In Rio 2016, a further tension is created between those who see sporting mega-events as part of a global pattern of exclusionary urban developments, and those who would project these mega-events as vehicles of ‘sport for development’.

But, while many acknowledge that the benefits accrued from hosting the Olympics are hardly distributed across a ‘level playing field’, most would more than likely cleave to the notion that ‘fair play’ prevails within the Olympic arena. And yet, as Claire Sullivan writes (2011) in the Journal of Sport and Social Issues, while ‘fair play’ is a fundamental tenet of international sport, quite how to delimit fair play has never been entirely clear. As a result, ‘fairness’ has, by and large, been enacted by policing and verifying gender difference. The question of gender verification and fair play has come to the fore once again at Rio 2016, as South African sprinter Caster Semenya prepares to participate in the Women’s 800m tomorrow. Semenya first came to prominence for vastly outperforming her rivals in 2009, after which she was subjected to a variety of humiliating and invasive gender tests. Semenya herself became the subject of an ‘ongoing spectacularization‘, and her defenders attempted (with little success) to navigate what Neville Hoad (2010) describes as the ‘long and intractable representational history of racialized and sexualized African bodies‘ on the one hand, and an ‘LGBTQ praxis of freedom that wants to render visible and celebrate gender variance’ on the other.

Writing in the Irish Times this June, the two-time Olympic silver medallist Sonia O’Sullivan objected to the idea that Caster Semenya might be able to run in the Women’s event in Rio. Deploying the same pseudo-sympathetic tone as Guy Martin, writing for The Daily Mail just yesterday, O’Sullivan argued that:

It’s through no fault of their own that these athletes have been born with more male genes and hormones than female; but this doesn’t mean they can simply be classified as women, and allowed to take part in women’s events…it was at least agreed by the IAAF and the IOC that these athletes would be entitled to compete, provided they underwent the treatment, which meant there was a level playing field with the majority of women athletes.

What concerns O’Sullivan (and Martin) is the fact that this requirement to take hormone therapy for those, like Semenya, who are deemed to have excess testosterone levels, was overturned last year, in response to an appeal launched by Indian sprinter Dutee Chand. For O’Sullivan, this allows ‘some athletes to take advantage of their genetic disposition’, while for Martin, ‘Regardless of whether or not she identifies herself as a woman, Semenya enjoys a physical advantage over her competitors’.

But why, if ‘fair play’ is to be policed along lines of genetic and physical advantage, is there such a persistent focus on gender verification and sex testing? As Silvia Camporesi wrote in The Conversation earlier this month:

More than 200 genetic variations have been identified that provide an advantage in elite sport. They affect a variety of functions including blood flow to muscles, muscle structure, oxygen transport, lactate turnover, and energy production. Endurance athletes in particular have been shown to have mitochondrial variations that increase aerobic capacity and endurance. An increasing number of performance-enhancing polymorphisms (genetic variations found at an increased frequency only in elite athletes and that make them who they are) are identified by sports geneticists.

More than this, we might ask why it is that O’Sullivan and Martin are so quick to naturalize the results of gender verification and sex testing. Writing in Signs, and based on archival work carried out at the IOC in Lausanne, Kathryn Henne (2014) has reviewed the history of sex testing and gender verification in the Olympics – beginning with the concerns in 1936 that men would masquerade as women, undermining the principle of fair play since, as Henne notes, the IOC has always worked with the idea that ‘Woman is inherently distinct from and less able than Man’. (Never mind that these early ‘gender frauds’ were not in fact winning out over their competitors in the women’s events.) In the 1960s ‘naked parades’ were deployed (at the 1966 Commonwealth Games), rendering gender verification and the assurance of fair play an essentially aesthetic matter. Aesthetics still seem to matter, with Semenya’s rivals back in 2009 stating ‘For me, she is not a woman. She is a man’ (Elisa Cusma Piccione) and, more brutally, ‘Just look at her’ (Mariya Savinov).

Chromosomal testing was used – with tragic consequences – until the 1990s, whereupon tests for DNA associated with testes growth were implemented. From proving their femininity, athletes competing in the women’s events were now asked to prove their non-maleness – and there was a possibility of re-instatement provided that no discernible ‘advantage’ was to be had from any ‘male’ attributes. Gender verification and sex testing has long been motivated by the notion that men competing in women’s events is the ultimate violation of fair play. But, contrary to Sullivan’s and Martin’s faux concerns about Caster Semenya ‘through no fault of her own’ simply not being ‘a woman’, Henne’s history shows us that, in ‘seeking to find the a priori boundary between Woman and Man, gender testing has constructed and reconfigured the limits of Woman, not found them.’ This brings to mind David Schneider’s (1980) classic work on American kinship, in which he argued that:

‘In American cultural conception, kinship is defined as biogenetic. This definition says that kinship is whatever the biogenetic relationship is. If science discovers new facts about biogenetic relationship, then that is what kinship is and was all along

In other words, if fair play (to those like Sullivan and Martin) is about policing the boundary between women and men, then that boundary is whatever the current IOC/IAAF approach to gender verification says it is. In Henne’s terms, ‘fair play’ appears as a ‘stand-in that justifies naturalized, not natural, difference’. More than this though, we might want to wonder, with Neville Hoad (2010), ‘How Caster Semenya can outrun a world that deploys all the power and authority of medical science to produce a claim that a poor Sepedi girl from rural Limpopo province has unfair and unnatural advantages’.

Further Reading: Sport & Gender in Sociology Compass

Grindstaff, Laura and West, Emily (2011) Hegemonic masculinity on the sidelines of sport. Sociology Compass, 5(1): 859-881.

Harkness, Geoff and Hongsermeier, Natasha (2015) Female sports as non-movement resistance in the Middle East and North Africa. Sociology Compass, 9(1): 1082-1093.

1540-6237/asset/SSSA_Logo-RGB.jpg?v=1&s=c337bd297fd542da89c4e342754f2e91c5d6302e)

9424 460255Some genuinely fascinating info, nicely written and usually user genial . 699326