This Cannot Be White-washed

by Deirdre Oakley* and Zuri Tau**, Georgia State University · Published · Updated

This essay introduces the latest issue of City & Community’s Symposium: “Eyes of a Storm: COVID-19, Systemic Racism, and Police Brutality.” I thank Dr. Alyasah Ali Sewell for coming up with the symposium title. There is free online access for the next month at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/15406040/2020/19/3.

This essay introduces the latest issue of City & Community’s Symposium: “Eyes of a Storm: COVID-19, Systemic Racism, and Police Brutality.” I thank Dr. Alyasah Ali Sewell for coming up with the symposium title. There is free online access for the next month at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/toc/15406040/2020/19/3.

During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, at least 675,000 people were infected in the United States and 500 million worldwide (Barry 2004). However, like today’s COVID-19 Pandemic, the infection rates were not evenly distributed across the United States. During the last pandemic, the United States was participating in the final battles of World War I, with over 700,000 Black men enlisted (Delaware Historic Affairs, 2020). The “Great Migration” of Black Americans from south to north was also accelerating because factory jobs needed filling. Yet, southern Jim Crow segregation and northern De Facto segregation meant that Black Americans with influenza were routinely turned away from White hospitals. In fact, Black hospitals were underfunded and overburdened by the pandemic (Brooks, 2020). Then, in 1919, came “Red Summer,” a summer in which White mobs raided Black communities across the north and south, inflicting destruction, violence, and death (Ortiz, 2020).

Most mainstream accounts of the 1918 Flu Pandemic gloss over the impact of this flu and the subsequent Red Summer violence on Black communities. This includes John M. Barry’s bestseller: “The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History,” published in 2004. Barry states, “…the 1918 influenza pandemic did not in general demonstrate a pattern of race and class antagonism…The disease was too universal, too obviously not tied to race or class. In Philadelphia, white and black certainly got comparable treatment” (p. 395). However, Erik Ortiz (2020) methodically refutes this conclusion by highlighting the parallels with COVID-19, systemic racism, and police brutality.

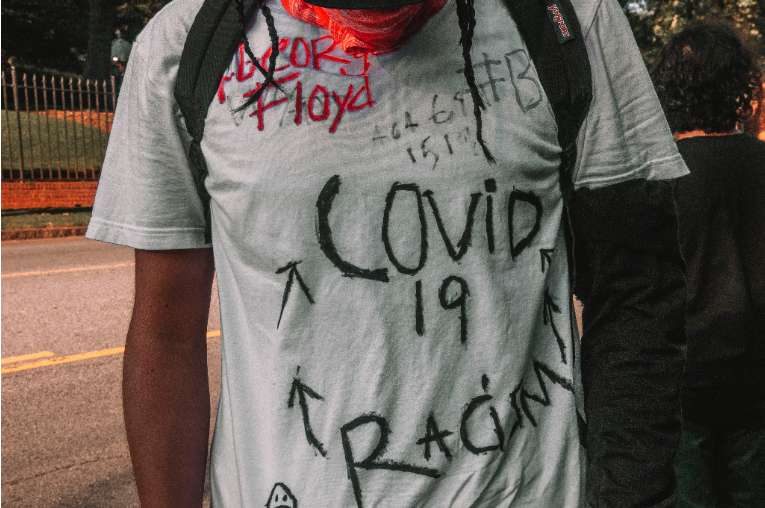

The purpose of this City & Community’s symposium is not to feature the similarities or differences between the 1918 Flu Pandemic and COVID-19. Instead, we document institutional links between COVID-19, systemic racism, and violence toward Black and Brown Americans, as well as globally. The six thought-provoking essays provide multiple perspectives into the current crisis. We hope this is inked permanently in history.

In the first essay, “Rending the Cosmopolitan Canopy”: COVID-19 and Urban Space,” Philip Kasinitz pens some of his observations and thoughts from New York City – one of the hardest hit cities in the country. He notes that frequenting public space, whether it be sidewalks, paths, parks, or markets is the quintessential urban experience. He discusses how withdrawal from such public spaces may have long term impacts on how Americans experience diversity. New York City is one of the most racially-segregated cities in the country but many often says things like ‘it doesn’t seem that way.’ This is because of experiences in the city’s public spaces. Kasinitz draws on Elijah Anderson’s 2011 book, The Cosmopolitan Canopy. Using ethnographic data from Philadelphia’s Redding Terminal Market, Anderson illustrates how people from different racial, ethnic, class and political backgrounds congregate without conflict. As Kasinitz states: “In such spaces, people who might be at odds in other settings not only tolerate each other’s presence—they actually enjoy it. Indeed, diversity becomes part of the appeal.”

In the second essay, “Policing the Block: Pandemics, Systemic Racism and the Blood of America,” Alysah Ali Sewell examines in what ways this pandemic has fundamentally altered how Americans share public space and who governs it. While congregating in crowded public areas is currently a public health issue, it has also allowed White-dominated institutions such as law enforcement to implement policies which put people of color at greater risk of being killed – not by the virus but by lethal force. She puts a name to the late George Floyd, who had been tested positive for the virus before being laid off and then murdered by the police: “Only in the systemic violence of this sociopolitical moment, could someone like George Floyd—a Black man living in a highly segregated city—die simultaneously of covid‐19 and police knees”.

In her essay, “Racism: A Public Health Crisis,” Katie Acosta emphasizes how this virus forces Americans to face up to the systemic racism embedded in “every fabric of our society.” The disproportional impact on Black and Brown communities should be a wake-up call. She also argues we need to link our critique of systemic inequality more thoughtfully to the protests over recent police violence. Black and Brown lives are already at risk because of the police: “Our lives are at risk regardless of if we are law abiding citizens. We carry the toxic stress we experience in our bodies where it festers weakening our immune systems and stealing our health.”

Jean Beaman turns to the global arena in her essay, “Underlying Conditions: Global Anti-Blackness Amid COVID-19.” She argues that the COVID-19 pandemic and the related police violence against Black individuals reveal a global anti-blackness. She uses examples from France’s banlieues (suburbs), where people of color live – whose parents, grandparents or great grandparents immigrated from former French colonial countries as French citizens. Residents of the banlieues have been blamed by the media for not abiding by quarantine orders. Beaman argues that this isn’t about rule-breaking, but the ever-present police surveillance and persistent marginalization of banlieues’ residents: “In other words, communities marginalized during the COVID‐19‐related quarantine are those marginalized before COVID‐19.”

In the next essay, “Examining the Relationship Between Institutional Racism and COVID-19,” graduate students Tyler Gay and Sam Hammer, along with professor Erin Ruel, examine how systemic racism frames the outcomes of COVID-19 and violence in Black and Brown communities where social determinants of health are already compromised. They refute biological, behavioral, and social class explanations for racial health disparities: “Racism was explicitly embedded into healthcare law from the early 19th through early 20th centuries. Healthcare law was the specific mechanism used to deny Blacks access to the same health care available to whites.”

In the last essay, Bruce Haynes returns to the issue of spatial containment but from a historical perspective. He documents through his own experience as a child growing up in the South Bronx, as well as historical information, how racial violence has always been characterized by White spaces – first informally and then codified by zoning, racial covenants, and redlining: “Whiteness itself has been an instituted privilege.” This alone has made Black and Brown Americans more vulnerable to pandemics and institutional violence.

Our hope is that if a new pandemic occurs in our lifetimes, systemic racism and all the inequality, blood, and death that goes with it, will no longer be a deciding factor of who is lost or who survives. Our symposium calls for this crisis not to be whitewashed, and joins with the efforts of activists, academics, and protestors across the country who fight to make it so.

References

Anderson, E. (2011). The Cosmopolitan Canopy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co.

Barry, John, M. (2004). The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History. New York, NY: Penguin Press.

Brooks, Rodney, A. (2020). “Why African Americans Were More Likely to Die During the 1918 Flu Pandemic.” The National Archives, October 5. https://www.history.com/news/1918-flu-pandemic-african-americans-healthcare-black-nurses.

Delaware Historical and Cultural Affairs (2020) “Patriotism Despite Segregation” DHC. Delaware Historical and Cultural Affairshttps://history.delaware.gov/african-americans-ww1/#:~:text=After%20the%20declaration%20of%20war,had%20registered%20for%20military%20service.

Ortiz, Erik. (2020). “Racial Violence and a Pandemic: How the Red Summer of 1919 Relates to 2020.” NBC News, June 21. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/racial-violence-pandemic-how-red-summer-1919-relates-2020-n1231499.

*Deirdre Oakley is Professor of sociology and an affiliate faculty member of the Urban Studies Institutes at Georgia State University. She is also the current Editor-in-Chief of City & Community. You may contact her at doakley1@gsu.edu.

**Zuri Tau is a sociology PhD student and principal at Social Insights Research. She is also the managing editor of City & Community. You may contact her at zcroson1@gsu.edu.