Populism, policy and pandemics

by Ewen Speed and Russell Mannion · Published · Updated

Photo: from Dr Case flickr photostream under creative commons CC BY-NC 2.0

Across the globe there has been an upswing in populist right wing political parties in the past decade. This raises a number of particular challenges for the provision of health and social care. For example, witness the cross-country disparities in excess mortalities linked to COVID-19. If we look at countries with right wing populist leaders (e.g. USA, Brazil) compared to other countries (e.g. New Zealand). Much of this difference can be accounted for by the populist rejection of expertise and scientific knowledge, e.g. both Trump and Bolsonaro advocated the use of hydroxychloroquine despite unproven efficacy. For a cross country comparison of how populist responses to the pandemic have played out across different countries see the populism and the pandemic collaborative report edited by Katsambekis and Stavrakakis.

It is important to note that the invocation of populist politics into health policy is not novel to COVID-19. Much of the populist health policy works to create a set of particular barriers and challenges for access to healthcare and the health of populations. Whilst the challenges are largely self-evident, there has been very little exploration of the implications for health policy.

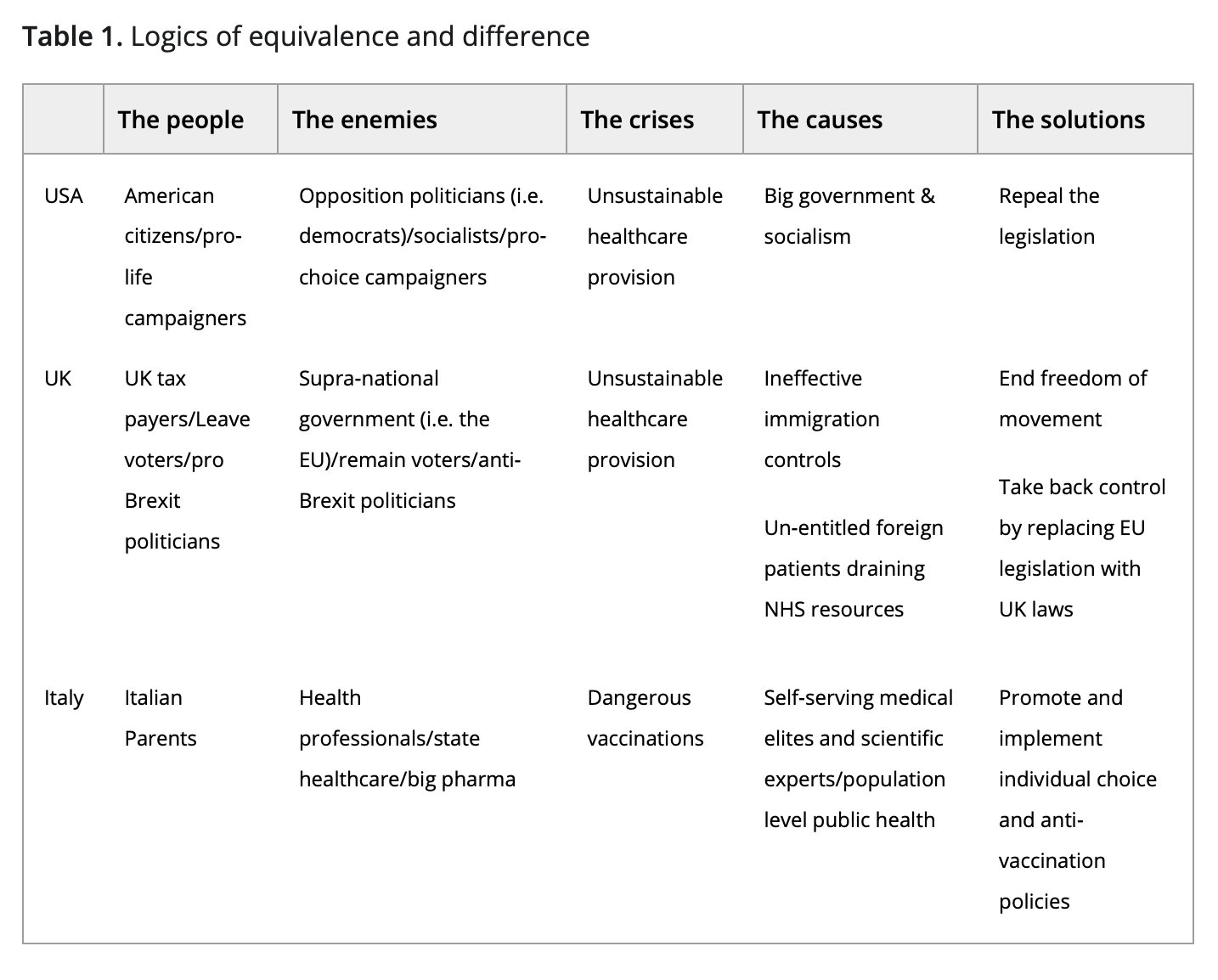

In a recent paper we considered three international cases to explore the ways in which right‐wing populism impacts on health policy. In the USA, we considered the election of President Trump and subsequent attempts to reform the Affordable Care Act, (so called Obamacare). This example demonstrates how the role of government in the provision of healthcare can be problematised by right wing populists. In the UK, we considered discussions around Brexit in the context of the UK National Health Service, outlining how issues of immigration and nativism played to notions of welfare chauvinism and how this can limit universal access to healthcare. In Italy we considered the rise of a politically aligned anti‐vaccination movement, which demonstrates the ways that experts and expertise can be problematised by populist policy. We are not suggesting that these health systems are comparable. Each example demonstrates different aspects of right-wing populist policy. By identifying the influence of common populist practices across three different contexts, we surface the myriad ways in which right‐wing populist politics serve to prioritise (or marginalise) particular approaches to health policy. Many of these processes are also surfaced in relation to how different countries have responded to COVID-19.

Our analysis demonstrates the implications of these populist politics. In the US, much of the legitimacy for reforming the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was cast in terms of promoting ‘socialized medicine’—and therefore un‐American. This is clearly a nativist position, but by opposing the Act, it was also the case that Trump was simultaneously (and somewhat contradictorily) operating against the best (healthcare) interests of (all of) the people – 9 million more US citizens were allowed access to health insurance because of the ACA. This nativism resonates with claims that dispute the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine and face masks, whereby right-wing supporters were predominantly pro-hydroxychloroquine and anti-mask. A key component to accomplishing this populist turn involves ensuring that the groups being interpellated into the populist performance feel that the populist politicians are speaking to the general will of the people. This is despite the fact that such actions might actually be detrimental to their health.

Nativism also plays out in the context of immigration. The UK NHS relies on the principle of freedom of movement within the EU to gain access to a skilled healthcare workforce. Populism, on the other hand, plays out against a background of national protectionism, and seeks to limit international cooperation and movement. But there is a strong possibility that staffing in the NHS will reach unsustainably low levels without this migrant workforce. If the ‘popular’ mood within the country is anti‐immigration, and if NHS levels of performance worsen because of the lack of migrant labour, the simple solution (i.e. employ more migrants) becomes harder to implement. Again, the populist agenda appears to be operating against the best health interests of the population.

It can prove difficult to counter these claims, as a central component of the populist playbook is a distrust of all forms of professional expertise. In Italy, over the past five years a populist led Anti‐Vaccine movement has questioned the safety of mandatory vaccination policies, corresponding with a drop in MMR vaccination in Italy from 90% in 2013 to 85% in 2016. The Anti‐Vaccine movement has promoted the idea that vaccinations are linked to autism. In 2018, the right‐wing, anti‐immigrant Lega Party, and the anti‐establishment Movimento Cinque Stelle (5‐Star Movement) both campaigned with Anti‐Vaccine groups, promising to repeal the law that made vaccines mandatory for children. Beppe Grillo, the 5‐Star movement leader, backed the idea of hazardous ‘measles parties’ where children gather to infect each other and build up immunity, mirroring US reports of ‘COVID parties’. In this example, ‘the people’ are portrayed as victims of the political and medical establishment who are depicted as being in the pocket of big pharma to promote a profit driven health policy that causes autism in children. Again, in the face of increased levels of morbidity and mortality, this populist policy operates against the best health interests of the population. These examples are summarised in table 1.

The political value of populist strategies is largely self‐evident in terms of the purchase it gives politicians in reforming healthcare systems. Populist practices can promote a range of particular social, political and economic inequalities in population health. If health policy is to remain a process whereby government provides a level of healthcare to all of the population, the role and influence of populism on health policy needs to be better understood in order to safeguard universal access and promote equity of treatment and access for all groups. This will become increasingly salient post-lockdown with rising economic insecurity (and the potential for a second wave of infections) fuelling xenophobic claims with migrants being blamed for limiting the ability of ‘native’ citizens to access health and welfare services. Similarly, there are very real concerns about how the populist right will mobilise around the implementation of a COVID-19 vaccine, as and when that might become available.

Authors: Ewen Speed1 & Russell Mannion

1corresponding author

Author Information:

Ewen Speed is a medical sociologist currently with an interest in the relationship between citizenship (in all its guises) and healthcare provision. He has published a number of articles on the interplay between health policy and populism. He is a founding co-editor of the Cost of Living blog (www.cost-ofliving.net). @EwenSpeed

Russell Mannion is Professor of Health Systems at the University of Birmingham. He has published widely on health policy and management, and with Ewen Speed, has published a number of articles on populism and health policy.

1540-6210/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=812a48e1b22880cc84f94f210b57b44da3ec16f9)

1468-0491/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=859caf337f44d9bf73120debe8a7ad67751a0209)