Is America Coming Apart?

by Elizabeth Roe and Jonathan Mijs · Published · Updated

Income and wealth inequalities in the United States are ever widening, and it is having a knock-on effect on segregation. Consider your own life. When you think about the people with whom you interact most, both socially and professionally, it is likely that your neighbors, classmates, and coworkers come to mind. This makes sense, as we come to spend a great deal of our time in our own schools, our own neighborhoods, and our own workplaces. Now consider the socioeconomic diversity of these social groups. Do these people drive the same types of cars as you? Do they live in similar housing? Do they have similar educational attainments? If you are answering “yes” to these questions, you are experiencing first-hand how intensely socioeconomically segregated the United States really is today. But hasn’t it always been this way?

Income and wealth inequalities in the United States are ever widening, and it is having a knock-on effect on segregation. Consider your own life. When you think about the people with whom you interact most, both socially and professionally, it is likely that your neighbors, classmates, and coworkers come to mind. This makes sense, as we come to spend a great deal of our time in our own schools, our own neighborhoods, and our own workplaces. Now consider the socioeconomic diversity of these social groups. Do these people drive the same types of cars as you? Do they live in similar housing? Do they have similar educational attainments? If you are answering “yes” to these questions, you are experiencing first-hand how intensely socioeconomically segregated the United States really is today. But hasn’t it always been this way?

Turns out the answer is no. In the past fifty years, wealth and income inequalities have grown exponentially, and today, they are at their highest levels since the Great Depression. As of 2017, the richest 1% of Americans own more wealth than the bottom 90% combined, and the top 10% take home a third of all earnings. The middle class is disappearing, leaving an enormous gap between the rich and poor. The issue of inequality in the US is virtually undisputed and is a topic present in discourse across the political spectrum. For example, in “Coming Apart: The State of White America,” Charles Murray argues that “class strain has cleaved society into two groups (…): an upper class, defined by educational attainment, and a new lower class, characterized by the lack of it.” Meanwhile, on the left side of the political spectrum, politicians like Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren make narrowing inequalities a priority for future policy.

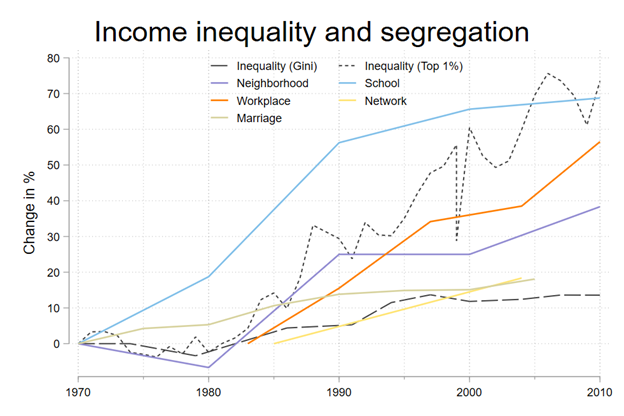

As socioeconomic inequality has increased over the past fifty years, socioeconomic segregation has grown with it. In a recently published article in Sociology Compass, my coauthor, Jonathan Mijs, and I describe the changing US social landscape by analyzing trends in socioeconomic segregation since the 1970s among four pillars of life: 1) social networks, 2) neighborhoods, 3) schools, and 4) workplaces.

We find that segregation has increased across each of the four aforementioned central aspects of life since 1970. First, compared to 1970, Americans in 2020 were much more likely to form romantic relationships and friendships with people of their own socioeconomic statuses. Indeed, in recent decades, educational homophily (the tendency of people to form and maintain relationships with similarly educated people to themselves) has increased by about 20 percent. Neighborhoods, too, have become increasingly segregated – neighborhood income segregation grew by roughly 25 percent between 1970 and 2021. Especially in recent decades, the concentration of affluence in neighborhoods has skyrocketed, so ultra-rich Americans are increasingly clustered within the same geographic areas. In addition, socioeconomic segregation in the education system has widened. Now more than ever, rich and poor children are separated all the way from preschool throughout post-secondary education. Finally, workplaces are becoming more and more polarized, as the gap between “good jobs” and “bad jobs” widens. Today, high-wage and highly educated workers work in entirely different companies and even industries than their lower wage, less educated peers.

The mechanisms fusing socioeconomic inequality with socioeconomic segregation are manifold. For example, as inequality grows, neighborhoods are increasingly defined by socioeconomic homogeneity due to zoning laws and the fact that housing prices are influenced by the cost of nearby housing. Furthermore, America’s public-school system is funded by local property taxes, meaning that, as neighborhoods become more segregated, public schools become more segregated, too. Similarly, in many workplaces, colleagues hired often have roughly equal educational levels and potential for income. As the education gap widens, workplaces become more stratified. With all of these factors compounding, there is simply little opportunity for interaction between the rich and poor. Consequently, people’s social networks become increasingly homogeneous, and there are fewer friendships and romantic relationships between people of different economic backgrounds.

Figure 1. Trends in income inequality and socioeconomic segregation in neighborhoods, schools, workplaces, social networks and marriage formation

Note. Change in percentage is calculated relative to its starting point in 1970.

Source: Mijs & Roe 2021

It is evident, then, that in spite of the current clamor for “woke-ness,” Americans today are far less integrated with people of diverse socioeconomic backgrounds than they were 50 years ago. America’s rich and poor share fewer spaces and form fewer relationships with each other. This trend is unlikely to abate without intervention; as income inequality compounds, Americans can expect to become even more socioeconomically segregated with each passing year.

The impact of this social segregation is profound. With greater segregation comes less social mobility, fewer shared identities, and a lower sense of solidarity. America’s people are increasingly fractured: rich versus poor, urban versus rural, educated versus uneducated. We have only to look at the regrettable state of our current political divide to see how polarized the population has become. The so-called “American Dream” comes apart at the seams, and so do Americans themselves. Our review article paints a grim picture of trends thus far, and there is no evidence that these trends will turn around by themselves. The current pandemic has only exacerbated wealth and income inequality, which will likely accelerate the upwards trend of segregation.

To head off this trend, we must make greater efforts to integrate Americans across all socioeconomic strata. To do so, government policies must expand opportunities for cross-group interaction for all people, but especially for children during their formative years. This may come in the form of building what Eric Klinenberg refers to as “social infrastructure,” communal spaces, churches, childcare centers, public libraries, and parks in order to encourage and facilitate relationships among social classes. In addition, prioritizing affordable housing and accessibility of good schools will allow greater diversity in the neighborhoods and schools in which we spend so much of our time. With a better integrated society, social mobility can grow, political divisions will narrow, and disparities will be reduced. America can come together once again.

The full article in Sociology Compass is available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/soc4.12884

Article reference:

Mijs, Jonathan J. B., and Elizabeth L. Roe. 2021. “Is America Coming Apart? Socioeconomic Segregation in Neighborhoods, Schools, Workplaces, and Social Networks, 1970–2020.” Sociology Compass e12884. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12884.

1540-6237/asset/SSSA_Logo-RGB.jpg?v=1&s=c337bd297fd542da89c4e342754f2e91c5d6302e)