Coronavirus reflections: Face masks, Islamic dress and colonial differentiation.

by Kimberley Brayson, Lecturer, Leicester Law School, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK Email: Kimberley.brayson@le.ac.uk · Published · Updated

Like many countries across the world, France is currently negotiating the coronavirus pandemic and has recently begun to emerge from lockdown by circulating a slogan not dissimilar to the UK government ‘Sauvez des vies, restez prudent’ (Save lives, stay alert). What then is so notable about the French plan to tackle coronavirus and be free from lockdown? Aside from the bureaucratic plan developed in France, the significant and noteworthy method of returning to some sense of ‘normalcy’ is to mandate the wearing of face masks. As of the 11 May wearing face masks has become compulsory in French public space. This is despite earlier claims by French government spokesperson Sibeth Ndiaye, that face masks were so unfamiliar to French society that wearing them was too difficult technically and could even be “counterproductive.” Early attempts to legally mandate the wearing of medical face masks were also struck down by administrative courts in France.

Like many countries across the world, France is currently negotiating the coronavirus pandemic and has recently begun to emerge from lockdown by circulating a slogan not dissimilar to the UK government ‘Sauvez des vies, restez prudent’ (Save lives, stay alert). What then is so notable about the French plan to tackle coronavirus and be free from lockdown? Aside from the bureaucratic plan developed in France, the significant and noteworthy method of returning to some sense of ‘normalcy’ is to mandate the wearing of face masks. As of the 11 May wearing face masks has become compulsory in French public space. This is despite earlier claims by French government spokesperson Sibeth Ndiaye, that face masks were so unfamiliar to French society that wearing them was too difficult technically and could even be “counterproductive.” Early attempts to legally mandate the wearing of medical face masks were also struck down by administrative courts in France.

Islamic dress in France

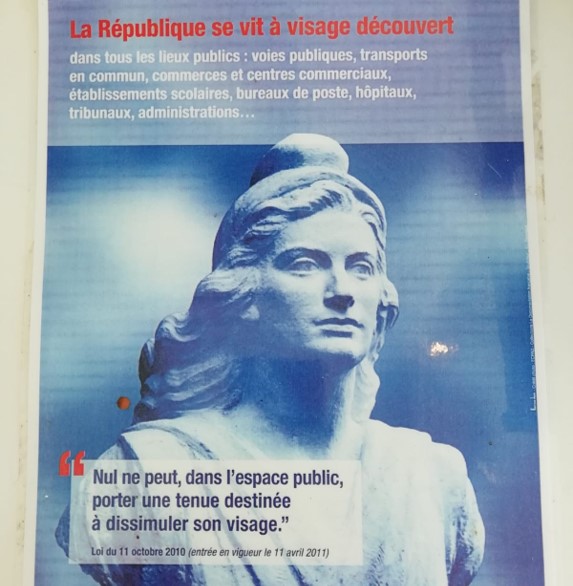

These constitutional issues are interesting, but I am primarily concerned here with how uneasily this discussion about face masks sits with another debate in recent French history: the debate on full-face coverings and Islamic dress in French public space. The Independent obliquely refers to it in this headline of 28 April 2020, prior to the face mask mandate being put in place: ‘France unveils plans for lifting lockdown.’ The play on words here, unintentional or not, speaks to the significance and hypocrisy of the French approach to emergence from coronavirus lockdown. This method of mandating face masks in French public space contradicts France’s own law 2010-1192, which criminalises full face coverings in French public space and has been held to stand up to human rights scrutiny at the European Court of Human Rights.[1] The image accompanying this blog is a poster that advertises and circulates this law, emphasising that ‘the republic lives through an uncovered face’. This functional distinction between the French approach to mandating medical face masks and to banning forms of Islamic dress only holds up if one accepts the colonial logic functioning at the heart of the French republic. This means that the difference in approach here is not merely contradictory, it is a deliberate moment of colonial differentiation.

Scholars, Fatima Khemilat, Olivier Roy and Joan Wallach Scott have all highlighted the asymmetric and incoherent nature of the French coronavirus mandate to wear face masks. As Wallach Scott points out, the secular versus Muslim dichotomy is operating so that nobody in France sees it as contradictory at all. The mandating of face masks for reasons of public health is an accidental admission that law 2010-1192 was intended to specifically target Muslim women and Islamic dress and is the imposition of a normative western liberal equality onto France’s Muslim population. This accidental admission coincides with case law at the Conseil d’Etat, which has exposed this law to be specifically aimed at Muslim women.[2] This is despite ongoing claims to neutrality on the part of the French state that the law bans all face coverings equally.

Christine Delphy has argued that justifications relating to gender equality and framed in terms of feminism in the Islamic dress debate in France are in fact politicians’ arguments.[3] As I have argued elsewhere and summarised in a previous blog on this site, the pursuit of gender equality restyled as a pillar of the French republic that considers Islamic dress to be a de facto form of gender oppression coupled with the appropriation of a discourse of feminism in order to justify laws criminalizing full-face coverings, obscures the colonial logic and radical exclusions of colonialism at play in the Islamic dress debate. This means that shifting legal justifications of gender oppression and national security simultaneously obfuscate and enact a strategy of cultural and colonial assimilation that controls and regulates Islamic bodies in public space.[4] The mandating of medical face masks in French public space reveals even more clearly the argument that laws regulating and criminalising Islamic dress enact and obfuscate colonial assimilation.

The logic of colonial differentiation

The reimagining of medical face masks as a new mode of Paris fashion to defeat coronavirus while face coverings related to Islamic dress are criminalised, demonstrates not only the hypocrisy of the French approach to full-face coverings but lays bare a hierarchy of colonial differentiation at the heart of the French republic. The functional reasoning employed by the French state in relation to the different face coverings only works from a foundation of this colonial logic and a racialised hygiene binary.

I have discussed elsewhere the effect of law 2010-1192 in enacting an institutional Islamophobia that acts like racism,[5] creating a whiteness of public space and institutions[6] and imposing legislative maps of exclusion in France. However, the current paradoxical situation in France brings into sharp focus the normative impulse of colonial differentiation at the heart of the modern French republic, whereby France sought and continues to seek to differentiate itself from its former colonies. In doing so the modern French republic attempts to show that it is not like its former, now administratively independent, colonies, it is something different, some distinction between the two must still prevail.[7] As Kristin Ross has argued this manifests in a racial differentiation that is fundamental to the project of French post-war modernisation and is circulated in a French discourse of hygiene.[8] This logic of hygiene refers not merely to cleanliness but to the racial purity of the secular, modern, capitalist French republic.

Laws criminalising Islamic dress play a cleansing role to immunise against the fear of racial impurity[9] and to cleanse French public space of colonial bodies and markers. This is done to aid the forgetting of the reality that the French modern republic relied and continues to rely on the exploitation of geographical colonies in the past and colonial bodies in the present. This duality of modernity/coloniality,[10] constitutes the French republic and is reflected in the simultaneous pursuit of colonial assimilation whilst maintaining a hierarchy of difference and colonial differentiation. The colonial bodies of Muslim women who wear Islamic dress are criminalised through law and are the site of the racial and gender difference upon which the French republic relies for its existence. Muslim women are thus necessary to the maintenance of the French republic and are instrumentalised through their oppression to perform this political function of colonial differentiation in France.

Ordinarily this ideological fear of racial impurity and norm of colonial differentiation is obfuscated by justifications relating to gender oppression and national security in the Islamic dress debate in France. As Ross argues the success of the modernity/coloniality dialectic as the mode of existence of the French republic is maintained precisely by ‘keeping the two stories separate’. In presenting an immediate threat to life and the health of the French nation, the current global coronavirus pandemic has unintentionally brought the stories of modern France and colonial exploitation together through the narrative of face coverings. One face covering, the medical face mask, is acceptable and mandated because it refers to a modern, scientific, hygienic French nation. The other face covering, Islamic dress, is unacceptable and criminalised because it refers to a colonial, backwards, racial un-hygiene. This exposes the normative hierarchy of racial and colonial differentiation as the logic of the French republic. This manifests as Islamophobia and racism and is emphasised through the current application of rules surrounding face coverings in France, which is not merely contradictory but deliberate in enacting the logic of colonial differentiation of the French republic.

[1] SAS v. France (2015) 60 E.H.R.R. 11.

[2] Conseil d’Etat, decision du 7 October 2010 no. 2010613, at <http://www.conseil constitutionnel.fr/conseil-constitutionnel/francais/les-decisions/acces-par-date/ decisions-depuis-1959/2010/2010-613-dc/decision-n-2010-613-dc-du-07-octobre2010.49711.html>.

[3] Christine Delphy, Separate and Dominate: Feminism and Racism after the War on Terror, tr. D. Broder (2015) 139.

[4] Kimberley Brayson, ‘Of Bodies and Burkinis: Institutional Islamophobia, Islamic Dress and the Colonial Condition’, (2019) Journal of Law and Society 46:1 55-82

[5] Rhonda Itaoui, `The Geography of Islamophobia in Sydney: mapping the spatial imaginaries of young Muslims’ (2016) 47 Australian Geographer 261, at 262.

[6] Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (2006), at 112.

[7] Kristin Ross, 1994 ‘Starting Afresh: Hygiene and Modernization in Postwar France’ October, Vol. 67: 22-57, at 26

[8] Kristin Ross Fast Cars, Clean Bodies: Decolonization and the Reordering of French Culture (MIT Press 1996), at 11.

[9] Isabell Lorey, State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious Verso 2015, at 37.

[10] Ramon Grosfoguel, (2011) ‘Decolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political-Economy: Transmodernity, Decolonial Thinking, and Global Coloniality’, TRANSMODERNITY: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World, 1(1)

1530-2415/asset/SPSSI_logo_small.jpg?v=1&s=703d32c0889a30426e5264b94ce9ad387c90c2e0)