How to understand social change and stability through discourse and communication?

by Susana Batel & Paula Castro, Centre for Psychological Research and Social Intervention, University Institute of Lisbon · Published · Updated

This is a summary of a paper, published in the British Journal of Social Psychology, that presents a theoretical proposal for integrating two (historically estranged but often combined in practice) social psychological frameworks, as well as a methodological strategy for analysing discourse and communication, developed from this integration.

The goals pursued with it are those of advancing a more socially relevant Social Psychology, more capable of comprehending how meanings are constructed and transformed in discourse and communication, as a way to better understand how social change and stability are made to happen. Here we are referring to such examples of social change as women gaining the right to vote from 1918 in the UK; or the approval in 2014 in Uganda of an Anti-Homosexuality Act that commits to life in prison whoever has same-sex sexual relations. The (multiple) meanings of what it is to be a woman, a citizen, or an homosexual are necessarily involved in changes such as these, and the social sciences and particularly social psychology have since their incept attempted to better understand how – in the relations between individuals and societies/collectivities – meanings are constructed, and transform or stabilize. For that, they have proposed several theoretical frameworks and associated methods. With this work we review, discuss and articulate some of those frameworks and methods with a view to devising a stronger method for analysing discourse and communication, seeking a better understanding of social change.

In social psychology´s history two of the main frameworks proposed to examine meaning-making in discourse and communication are the theory of social representations (TSR) and discursive psychology (DP). Dialogical and critical approaches to TSR propose how meaning-making – or re-presenting – happens in and through relations, that is, with an other. This other is multiple – it is our interlocutor of a conversation at the pub, our interviewer in a research interview, our other selves with whom we converse ‘inside our heads’, as well as the institutions and legislations regulating those interactions. This implies then as well that TRS is also quite attentive to how power relations shape meaning-making.

As for DP, within Social Psychology this tradition was very important in highlighting the performative and political powers of language, as well as the relevance of analysing power relations at a structural level and how those constraint social change.

Despite their story of lack of dialogue, TSR and DP share important assumptions and complementarities: the focus on interaction and the relational as where social change happens; the focus on discourse and communication as how to access the relational; the acknowledgement that there is inter- and intrasubjective variability in meaning-making; and that meaning-making is both dependent on and can contest power relations.

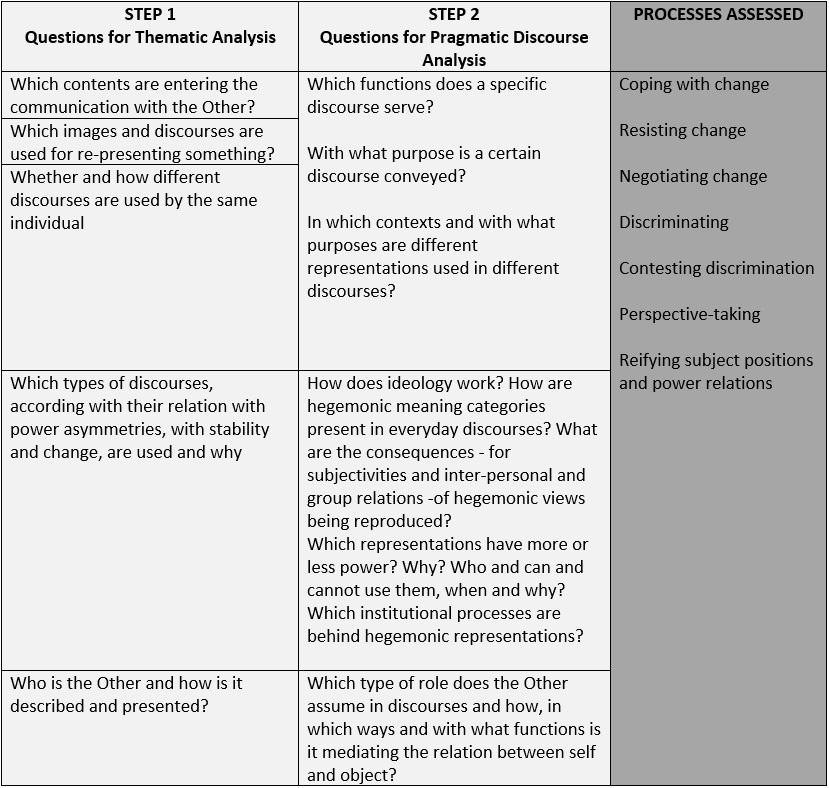

It might be useful then to combine TSR and DP, their similarities and complementarities, for a better understanding of how social change and stability happen through discourse and communication. For that we propose a two-step analytic method that, by joining thematic analysis and pragmatic discourse analysis, is able to analyse simultaneously the contents, formats and processes involved in discourse and communication and, with it, how the everyday interactions and communication (d’) reproduce and/or contest hegemonic and institutionalised discourses and practices (D’). The first step, thematic analysis allows identifying the discourses being presented, and if different and contradictory ones exist, but it does not allow to understand why, in which contexts, and for what they are (or are not) being used. Pragmatic discourse analysis examines the effects of different discourses. This implies looking at what functions discourses serve and what strategic interests are being pursued, therefore clearly focusing on the political dimensions of self-other relations, but also considering how those are constrained by institutional and ideological conditions. This analytic method is illustrated in the following table:

TABLE 1 – A systematization of the questions that can be answered by Thematic Analysis’ focus on content (Step 1) and by Pragmatic Discourse Analysis’ focus on function and process (Step 2)[1]

This proposal does not aim to be a strict guide of step-by-step rules for examining discourse and communication. We view it instead as not only a useful proposal for conceptual and methodological integration seeking a social-psychological theorization of meaning-making, but also as a relevant set of insights that can be more easily learned by students. This is particularly necessary because neither TSR nor DP are mainstream epistemologies within social psychology and thus are often forgotten in social psychology modules and handbooks.

[1] For more information on relevant analytical tools to answer these questions, see Batel & Castro (2018). British Journal of Social Psychology, 57, 732-753.

Author biographies

Susana Batel, PhD, Integrated Researcher at CIS – Centre for Psychological Research and Social Intervention – at the University Institute of Lisbon (ISCTE-IUL). My research adopts a critical perspective to examine the relationship between re-presentation, identities, power, discourse and communication, and social change, namely regarding public participation in environmental issues, and public responses to renewable energy and associated technologies. I am co-Editor of the journal Papers on Social Representations.

Paula Castro, Professor of Psychology at ISCTE-IUL and integrated researcher at CIS-IUL. I develop a socio-political analysis of the meaning-making and communicative processes involved in social change that is promoted by new laws and policies. I have namely examined how the policies for biodiversity protection, climate change adaptation, urban regeneration or public participation are interpreted and received (e.g., contested, resisted, accepted, narrated) by individuals, communities and institutions, often focusing on the dynamics of public/expert relations.

1099-1328/asset/dsa_logo.jpg?v=1&s=e4815e0ca3064f294ac2e8e6d95918f84e0888dd)