How to make sense of the debate on “study drugs”?

“Medicalization“ as a theoretical concept has received much attention in sociology throughout decades and people’s drug use is a social phenomenon investigated from different perspectives in the social and life sciences. Research on “study drugs” is an area where many of these perspectives converge – not only because it prompts us to reconsider the treatment/enhancement distinction. In this article, Stephan Schleim describes how the topic of (allegedly) performance-enhancing drugs has fascinated him since high school. When scholars started discussing this as “neuroenhancement”, several things went wrong, he argues. Read on to find out whether students really use “study drugs” as much as is often reported and whether there might be an alternative way to make sense of people’s substance use.

In my final years at high school in Germany, I tried out highly dosed caffeine tablets that were sold only in pharmacies. But after a couple of weeks I concluded that their primary effect was to make me nervous and sweat more. I had not noticed any improvement of my (already very good) grades. Although I stopped this experiment with stimulants after only a short time, my schoolmates still wrote about me in our yearbook: “Stephan takes caffeine instead of sleep.”

A few years later, now in the early 2000s, while I was a university student, “cognitive enhancement”, later “neuroenhancement”, and sometimes also “brain doping” were increasingly discussed in academia and the media. Some professors (rather carelessly, as we will see) suggested that breakthroughs in neuroscience would soon lead to the development of new drugs and technologies that would make us all smarter. And vast numbers of students, it was repeated over and over again, would already use “study drugs”. That was when both the Human Genome Project and the Decade of the Brain had just been completed – and “neuro-optimism” was prevalent.

“Prevalence” here is the keyword: For while ethicists, legal scholars, and scientists who collaborated in a new field they called “neuroethics” reported that 16 or even 25 percent of the students were already engaging in “cognitive enhancement”, the available studies provided quite a different picture: The most important investigation of that time reported a past-month prevalence of non-medical prescription stimulant use (like Adderall, Ritalin, and similar products) of only 2.1 percent, based on the answers of almost 11,000 students in the US (McCabe et al., 2005).

Creativity with numbers

This study became a citation classic in “neuroethics” and now has more than 1,100 citations on Google scholar. But how could it be that a publication reporting such a low prevalence – only 1 in 50 occasional or regular users – was used as evidence that vast numbers of students already did it? The answer is as simple as it is disconcerting: The data collected by Sean McCabe and colleagues came from 119 colleges throughout the US. And while the reported prevalence at 21 of these educational institutions was actually zero, there was one extreme outlier. At this college, 25 percent of the respondents stated that they had used the drugs non-medically at least once in the past year.

While we teach our students to handle outliers in such data with care, this extreme result got all the attention: Both scholars and journalists reported that at some campuses, one out of four students already used stimulants to study better. Besides being extremely biased, this message was also flawed in that “non-medical” use is something different than “cognitive enhancement”. After all, stimulants like amphetamine and methylphenidate, the active ingredients in the said ADHD medications, are also used to feel better, to party longer, or to lose weight. And those studies asking about the motives behind the reported non-medical use often confirmed that “recreational” or “lifestyle use” of these drugs was a major if not the primary reason.

A small number of academics, including myself, kept warning about exaggerated figures and inflated expectations (Schleim & Quednow, 2017; 2018). Not only is there no conclusive evidence that these drugs make (healthy) people smarter, their use without a doctor’s prescription can be punished by law and carries the risk of mental and physical side effects. Alas, the story that ever more students are using “study drugs” was too tempting to resist: It guaranteed research grants and clickable headlines in many countries around the world.

Into the parliament

Still in 2021, the newspaper of my own university (Groningen, Netherlands) wrote that non-medical use of prescription stimulants was a huge problem: “Stimulant use is alarmingly high: What student doesn’t love Ritalin?” The (non-representative) data actually came from a sample at my own faculty (Behavioral and Social Sciences). However, of the 1,071 students who responded, only two – thus a mere 0.2 percent – answered that they used such drugs regularly (Fuermeier et al., 2021). And, again, the majority did so for “leisure” instead of in an “academic context”.

This newspaper article was probably read by someone in the Dutch Ministry of Health who brought this topic to the attention to the (now: former) Secretary of State of a Christian party who then launched an initiative to discourage “non-intended use of ADHD medication”. The topic was even discussed by the Dutch parliament which then gave an institute specialized in investigating drug use the task to carry out a representative study. This found virtually the same prevalence rate as McCabe and colleagues had already reported in 2005: 2.4 percent of male and 1.5 percent of female students said that they had used prescription stimulants at least once in the last month. Eventually, the (new) Minister of Health concluded on June 30, 2022, that these are not dramatic figures and suggested to raise awareness for students’ stress and doctors’ prescription practices.

Medicalization

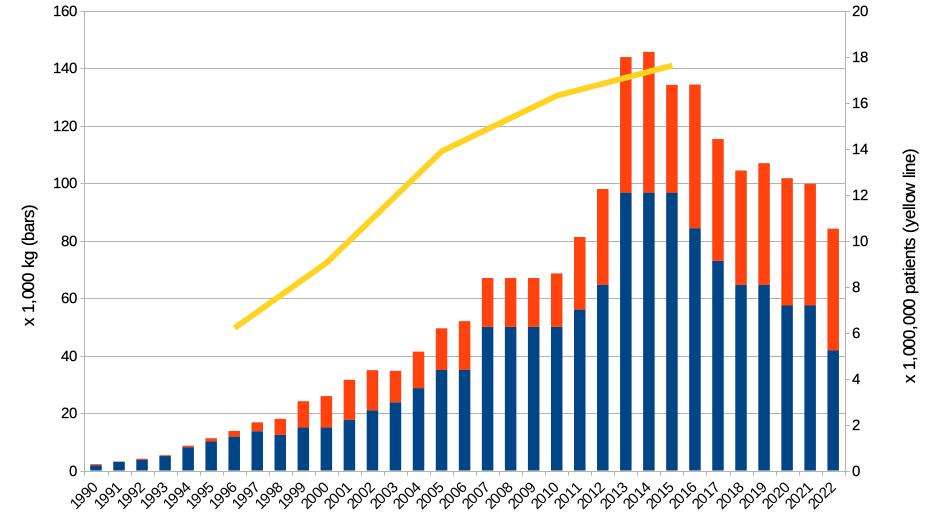

When one looks up earlier studies, it turns out that non-medical use of prescription stimulants has been much more common in the past and continuously decreased since the 1980s (Schleim & Quednow, 2017; 2018). However, it is also true that the production of amphetamine, already popular in the 1930s, and methylphenidate, a discovery of the 1940s, virtually exploded in the decades since the 1990s in the US (Figure 1). But doesn’t that contradict the low prevalence rates described above?

Figure 1: Annual Production of Prescription Stimulants in the US

These (seemingly) contradicting messages – decreasing prevalence, increasing production – can be reconciled by remembering what the surveys discussed above have been investigating: non-medical use. Figure 1 thus shows, for the US, how much more commonly stimulant drugs have been prescribed to treat ADHD since the 1990s (see also Bachmann et al., 2017). The increase in the Netherlands has been similar; the same is true for Denmark in Germany, though on a somewhat lower level, while these drugs have hardly been prescribed in the United Kingdom (Bachmann et al., 2017). This illustrates that not only the justification of giving impulsive and/or inattentive children, teenagers, and now also increasingly adults an ADHD diagnosis is a matter of debate (Lange et al., 2010), but also whether psychopharmacological drugs are an appropriate treatment.

In (medical) sociology, such processes have of course been discussed as “medicalization” or “pharmaceuticalization” for decades. These concepts are used to the describe the transformation of human conditions into targets for medical, or, in particular, pharmaceutical, treatment. Also here on Sociology Lens, there are many articles discussing this process. For our present purpose, let me point out the irony of the “neuroenhancement” debate: While many “neuroethicists” alarmed society that ever more students were using “study drugs” to become smarter – reframing and contradicting the available facts –, the non-medical use of stimulants continuously decreased. Note that for this invented social problem none else than the same “neuroethicists” were presented as the experts to look for solutions. Meanwhile, they neglected the really strongly increasing medical use, arguing that enhancement were categorically different from medical treatment – and that the latter were not a real ethical problem at all, or at least not a new one.

Summary & Outlook

Although I think that the ‘neuroenhancement’ debate rested on serious mistakes from its very beginning, substance use is an important social and academic topic, particularly for psychology and sociology: When one looks at this kind of human behavior through a wider lens than the concepts of enhancement or treatment allow, one finds many present, historical, and evolutionary examples for how drugs are used instrumentally to achieve different aims, including coping with life’s struggles, having fun, or gaining new experiences (Schleim, 2020). How this behavior should be regulated is an ongoing debate. But we presently see initiatives to legalize or at least less criminalize drugs in many countries, expressing the realization that the strict prohibition enacted in the course of the 20th century is neither successful in preventing use nor public health problems, as exemplified by the opioid crisis in the US.

We cannot discuss all problems and challenges related to substance use here. But to better inform people and particularly students wondering whether they should engage in “neuroenhancement” or “brain doping”, I compiled this “brain doping report” which summarizes 15 years of research (Schleim, 2022). When I was a PhD student, I eventually decided against writing a doctoral dissertation on this topic, concluding for myself that it is mostly a “hype”. I underestimated, though, how long this would continue in the scholarly debate and the media. For the future, I think that instrumental substance use is the best category to investigate this phenomenon in all its variety.

Author Information

Stephan Schleim holds a PhD in cognitive science and is associate professor for theoretical psychology at the University of Groningen. For more than 15 years, he has also been an active blogger, science writer, and expert commenting on recent trends in psychology and neuroscience in the media.

References

Bachmann, C. J., Wijlaars, L. P., Kalverdijk, L. J., Burcu, M., Glaeske, G., Schuiling-Veninga, C. C. M., . . . Zito, J. M. (2017). Trends in ADHD medication use in children and adolescents in five western countries, 2005-2012. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol, 27(5), 484-493.

Fuermaier, A. B. M., Tucha, O., Koerts, J., Tucha, L., Thome, J., & Faltraco, F. (2021). Feigning ADHD and stimulant misuse among Dutch university students. Journal of Neural Transmission, 128(7), 1079-1084.

Lange, K. W., Reichl, S., Lange, K. M., Tucha, L., & Tucha, O. (2010). The history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 2(4), 241-255.

Luo, Y., Kataoka, Y., Ostinelli, E. G., Cipriani, A. & Furukawa, T. A. (2020). National Prescription Patterns of Antidepressants in the Treatment of Adults With Major Depression in the US Between 1996 and 2015: A Population Representative Survey Based Analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 35.

McCabe, S. E., Knight, J. R., Teter, C. J., & Wechsler, H. (2005). Non‐medical use of prescription stimulants among US college students: Prevalence and correlates from a national survey. Addiction, 100, 96-106.

Schleim, S. (2020). Neuroenhancement as Instrumental Drug Use: Putting the debate in a different frame. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 567497. link: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.567497/full

Schleim, S. (2022). Pharmacological Enhancement: The Facts and Myths About Brain Doping. Groningen: Theory and History of Psychology, University of Groningen. link: https://doi.org/10.33612/227882920 Also available in Dutch [https://doi.org/10.33612/228411889] and German [https://doi.org/10.33612/228411702]

Schleim, S., & Quednow, B. B. (2017). Debunking the ethical neuroenhancement debate. In R. ter Meulen, A. D. Mohamed, & W. Hall (Eds.), Rethinking cognitive enhancement: A critical appraisal of the neuroscience and ethics of cognitive enhancement (pp. 164-175). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Schleim, S., & Quednow, B. B. (2018). How Realistic Are the Scientific Assumptions of the Neuroenhancement Debate? Assessing the Pharmacological Optimism and Neuroenhancement Prevalence Hypotheses. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 9, 3. link: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2018.00003/full

1756-2589/asset/NCFR_RGB_small_file.jpg?v=1&s=0570a4c814cd63cfaec3c1e57a93f3eed5886c15)