Sex, drugs and activism: making HIV treatment as prevention available in the UK

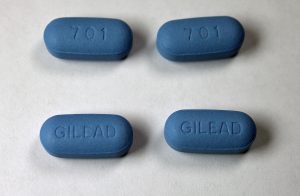

The anti-retroviral drug Truvada, which is a combination of tenofovir and emtricitabine.

On 10 April 2017, the Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) announced that PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) – the use of HIV treatment in people who are HIV-negative to prevent HIV – would soon be available on the NHS. This is a landmark decision for the use of HIV treatment as prevention in the UK, making Scotland the first – and currently only – country to provide PrEP through the NHS.

PrEP policy pathways

The Scottish pathway to this policy decision has been very different to that of England. Third sector and health policy organisations, community activists, clinicians and researchers came together in both countries to collate evidence about PrEP’s effectiveness and show how it might address a public health need for additional HIV prevention tools.

However, concerns around cost, judgements around ‘lifestyle’, and debate about responsibility for prevention contributed to a long and protracted debate and delay in England. This resulted in ongoing community campaigns (e.g. #united4prep) and legal actions demanding PrEP, and finally the promise of a new PrEP trial to enable access to PrEP in England, although little detail is currently available.

In contrast, and learning from the experiences of colleagues in England, the Scottish process appeared to be less hindered by bureaucratic decisions and negative public debates with expert working group and community consultation reports feeding directly into the decision. While policy processes and outcomes differed between the two countries, the language of cost-effectiveness, the framing of responsibility and the mobilisation of scientific knowledge within and by coalitions of activists have been critical in both of these stories.

Treatment as prevention – a lifestyle choice or an essential treatment?

PrEP has continually captured headlines – and imaginations – in the UK. Yet at the same time that clinical evidence for PrEP was released, international clinical trials found that HIV treatment in people living with HIV could also prevent its transmission. Unlike the very public debates of PrEP, HIV treatment as prevention in people living with HIV has moved forward as a policy decision with little fanfare. The most recent BHIVA Treatment Guidelines now recommend that HIV treatment be offered to all people living with HIV for the prevention of onward transmission. The difference with this and PrEP, it seems, is that treatment as prevention is not seen as a lifestyle choice, but as an essential treatment for people living with an illness.

One of the more interesting developments to emerge during this interim PrEP policy period has not only been growing activism demanding NHS provision of PrEP, but how coalitions of community and clinical actors have circumvented the formal health system to fill the gap. The creation of a website (Iwantprepnow.co.uk) to access generic PrEP for personal use has not only been embraced by NHS clinicians in the absence of state provision, but led to the provision of clinical support for the use of these otherwise privately acquired drugs ( i-Base 2016, Portman 2016).

In the context of a public-funded health system that needs to make both public health and budgetary choices, what are the implications of private acquisition of what some have called ‘essential prevention drugs’? While this do-it-yourself PrEP option is available to those in the know, who have sufficient income to pay for these drugs and who can navigate complicated regulations to import pharmaceuticals for private use, who does this leave behind?

Biomedicalisation, inequalities and implementation

The uneven implementation of this ‘new’ HIV science speaks to the ways in which the processes of biomedicalisation implicit in HIV treatment as prevention are not homogenous. As colleagues and I highlighted in our 2016 article in anticipation of the implementation of HIV treatment as prevention, understandings of cost and cost-effectiveness, ongoing stigma around ‘lifestyle choices’ or public health needs, and debates around responsibility for prevention continue to be woven through current policy processes and decisions.

With Scotland’s PrEP decision and the continued uneven access to PrEP across the UK, we need to consider how factors such as geography, ethnicity, gender, sexuality and money continue to play important roles in how scientific developments are translated in health and health policy. Given the increasing role of pharmaceuticals for prevention (Greene 2016, Lancet 2017), as well as the growing provision of pharmaceuticals outside of the formal, state-funded health system, we will need to be particularly attentive to ongoing implementation of HIV treatment as prevention. While many activists are celebrating a well-earned policy decision, this is by far the end of the story.

Ingrid Young is a Chancellor’s Fellow at the University of Edinburgh. She is currently funded by the Scottish Chief Scientist Office. This blog draws on Ingrid’s ongoing work in the translation of HIV treatment as prevention. Ingrid was a member of the Scottish Short Life Working Group who recommended the implementation of PrEP in Scotland.

References

Greene J, Condreau F, & Watkins ES (eds) (2016) Therapeutic Revolutions: Pharmaceuticals and Social Change in the 20th Century Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

i-Base (2016) UK Guide to PrEP i-Base collaborative publication (2nd edition) London.

Lancet editorial (2017) Polypills: an essential medicine for cardiovascular disease Lancet 389 (10073): 984.

Portman, M. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis: making history Sexually Transmitted Infections 2017: 93;7.

1467-7660/asset/DECH_right.gif?v=1&s=a8dee74c7ae152de95ab4f33ecaa1a00526b2bd2)