You are what you swallow? Considering the moral implications of psychiatric diagnosis for children

It’s not easy to question things that have been life changing for some people. As more and more people seek or receive psychiatric diagnosis, it becomes a very personal thing to question its validity. When I wrote an opinion piece in 2023 suggesting moral implications associated with increasing psychiatric diagnosis of children, I felt nervous. Nervous of invalidating the experiences of others but also nervous of the implications of questioning medical hegemony without undermining the hard fought for systems of mental health care, which remain globally, largely underfunded. The World Health organisation estimates that 970 million people worldwide are living with mental illness in any given year. This is not a small issue. But with increasing numbers of children also meeting the criteria of psychiatric diagnosis, I was really starting to wonder what the implications were of not questioning the validity of the systems that define ‘normal’ and ‘abnormal’.

I am not the first to wonder. Throughout history there have been numerous and ongoing challenges of psychiatry, including those by groups of its own disgruntled members (for example, Anti-Psychiatry movements or Critical Psychiatry) or those led by people who have found it personally harmful (for example, Consumer/Survivor/Ex-patient movements). Psychiatric diagnoses define the boundaries of what is assumed to be right and wrong (in behaviour, emotion and experience) and subsequently they are agents of morality. Yet, despite being an arm of medicine, Psychiatry is very different to every other part of medicine. We don’t really know if any of it is correct. There is no test for any mental illness; despite decades of research there is not yet any clearly identified ‘gene’ or neurotransmitter that we can be sure is the cause or effect of a clear pathway of illness. Diagnostic manuals remain checklists of symptoms, updated and altered relatively often, which cumulatively contribute to agreed-upon nomenclature of ‘disorders’, determined by consensus and clinical utility. Essentially, what counts as a disorder is based on speculative (although well-informed) assumptions of what is ‘normal’, and what falls outside of this. And these systems are developed within a wider context of social, political and cultural expectations of conforming, productivity and functioning.

While many may argue that mental illness surely does exist, and psychiatry has undoubtedly helped many people, the medical positioning of psychiatric disorders as illnesses implies that they are factual, scientific, and at least partially biological phenomena. Yet we also increasingly know that many of the functional impairments associated with diagnosis, are highly correlated to social, familial and environmental factors such as trauma, poverty or structural discrimination.

As adults, excluding when legally (or otherwise) coerced, we usually have opportunities to seek out different frameworks of understanding, to question implied truths and to choose how much a diagnosis may be interwoven with our sense of who we are as an individual. But what about children? Childhood is a period of development and vulnerability, dominated by discourses of protection and nurturance. It’s a time when adults are required to care for and make decisions on behalf of children. As adults, we warn children of risks and position ourselves as sources of knowledge of how best to stay safe, while also filtering how much knowledge they have of things, to preserve their innocence. Subsequently, what we tell children is ‘true’ or ‘real’ or ‘normal’ has weight and power.

In a healthcare context, there are often tensions between children’s right to autonomy and choice, and our obligation to protect them and keep them well. If a child is sick, as much as possible, adults will ensure they get treatment, even if they don’t want it. Because we know that it works, and as a society we have determined that they do not yet have capacity to decide against it. But what about in a mental health context? Childhood mental health is a relatively emergent field in the long history of psychiatry, with work continuing to evolve on what positive relational experiences and contexts infants and children require to thrive. Increasing awareness of the socio-ecological context of development and linkages between childhood adversity and lifetime health issues have been important drivers of public health approaches, social policy and health service development. Yet, alongside awareness of health comes awareness and delineation of variance, leading to staggering rates of children being diagnosed with mental disorders. Across studies, rates of child diagnosis are increasing more rapidly than rates in adult population and this is correlated to rapid rises in the prescription of powerful medications such as antidepressants and stimulants.

So, what does it mean to be diagnosed with a mental illness as a child? At times it means pathways into services and supports. In many places, diagnosis is required to ensure extra funding to be able to access support for children in school or at home. Medical expertise and technical language legitimise experiences and facilitate funding, policy and awareness. Diagnosis can mean access to treatments such as therapy or medication, from which many people benefit. For families it can bring relief and reduce the blame that can be associated with children’s behaviour or emotional distress. For children it can facilitate understanding, compassion, identity and connection to others with similar experiences, but it can also lead to internalised understandings of themselves as different, abnormal, incapable or bad.

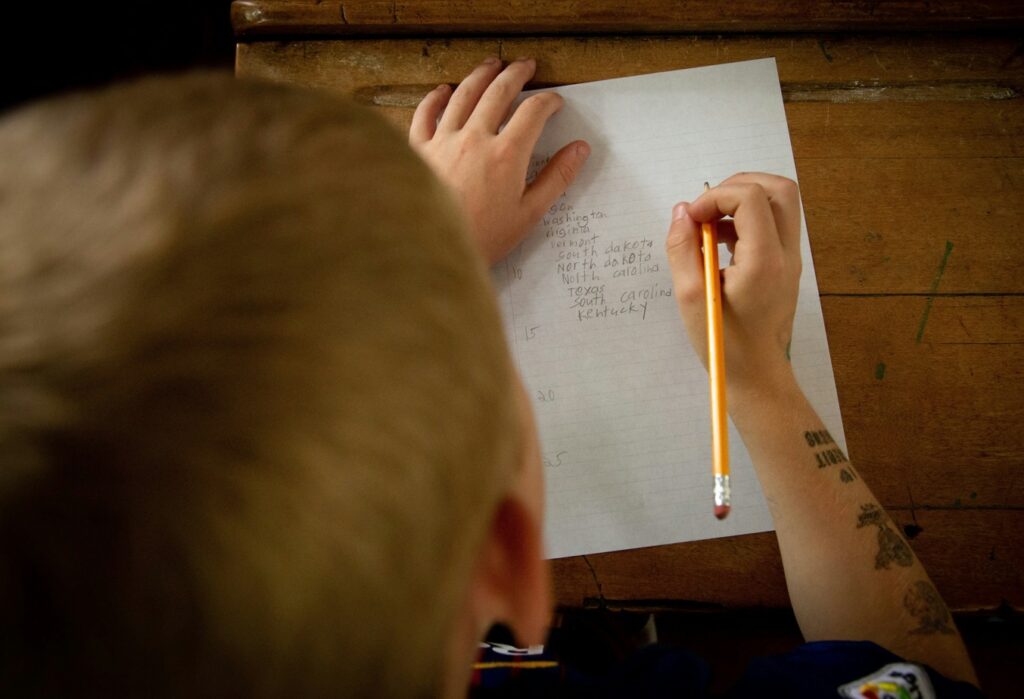

If for a moment, though, we zoom out from individuals and put aside what has helped me or you or someone we love, it’s beneficial to think on a social level about the moral issues that psychiatric diagnosis poses, particularly for children. Children develop their sense of who they are experientially and relationally. To be diagnosed with a disorder or illness impacts upon how children understand themselves individually and in relation to the world. Adults show diversity in how much they accept and integrate diagnosis into their identity and self. But without a fully formed sense of themselves before their diagnosis, what does it mean for a child to be told there is something ‘wrong’ with them? What are the implications of being labelled with an illness, without capacity to access or understand the meaning of the diagnosis and how it may differ from other physical illnesses they may be aware of? Do we tell children that we aren’t exactly sure if our system of classification and treatment is correct?

The impacts are also indirect. Children who have a parent with a mental illness are socially positioned as ‘vulnerable’ or ‘at risk’ – a burden often carried throughout their lives and leading to fear, vigilance, scrutiny and self-doubt, (alongside any support or positive impacts upon identity). Subsequently, the intergenerational impacts of raising rates of child diagnosis are not yet known.

Questions arising include, is psychiatric diagnosis of children a simplistic solution to a complex social and evolutionary issue? With increasing rapid access to information, our brains are rapidly altering, leading to changes in our attention span, range of vision, neurotransmitters and perceptions. With increasing sharing of information about global crises and impending climate and political doom, our brains are absorbing more fear and helplessness than ever before. Are children’s collective experiences of sadness, worry, distraction and disobedience reflective of wider social issues rather than a disruption in each individual child’s neurochemistry or structure? And if so, how do we tackle this and what alternatives to diagnoses and medication do we currently have for children or families who are experiencing life-interrupting distress?

I have worked within the mental health system as a clinician for much of my career. Even in more recent times as I have advocated for change in the way care is delivered, I remain part of the system to which I refer. Mental Health clinicians, regardless of our political, philosophical or moral beliefs, all act as agents of the psychiatric system and as such, we are obligated to stop and reflect on what drives and sustains the systems we are a part of. Disrupting assumptions about how problems are assessed, described and defined isn’t easy or comfortable, but it is necessary for unpacking harmful discourses. Critiquing current systems isn’t about the ethics of diagnosing or treating individual children who may benefit. In confusing times, we don’t need to ‘take a stance’ against something to be able to ask questions and allow space for considering alternatives.

Children are taught to listen to adults and trust in our care and decisions. As such, we all have a moral obligation to reflect on how both the problems of childhood, and their solutions, are constructed and to ensure we consider the implications of positioning the child as ‘the problem’ and telling them so in ways they can only assume to be true. Somewhere between abolition of psychiatric diagnosis (or ceasing to offer explanatory frames and treatment approaches that benefit some and harm others), and continuing on in the same way without (or despite) knowing the risks inherent in doing so, lies a path where we collectively, publicly and transparently consider what drives the status quo, and what the implications of it are for current and future generations.

References

Isobel, S. (2024). Considering the moral implications of psychiatric diagnosis for children. Children & Society, 38, 197–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12694