First People Lost: New Statistics Show Alarming Patterns in Indigenous Death Rates in Canada

The Canadian National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls has wrapped up its hearings and is scheduled to deliver its final report early next month. The Inquiry examines some of the most extreme outcomes of violence and marginalization of Indigenous women and girls, however the factors affecting their livelihood and life expectancy extends beyond these extreme outcomes and recent research suggests there may not be cause for optimism unless there is systemic change.

A research study recently published in the Canadian Journal of Economics shows alarming patterns in the mortality rates of Status First Nations people. The research uses administrative data from the former Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) from 1974 to 2013 to provide the most up to date and consistent time series statistics of Status First Nations mortality. The research was responding to the recent calls in Canada for reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada by helping to establish time series estimates of well-being

for Indigenous peoples. While cause of death was not possible to investigate with the INAC administrative data, my coauthor Randall Akee and I could examine how mortality varied relative to the general Canadian population by age, gender, location (on or off reserve and by province), as well as over time.

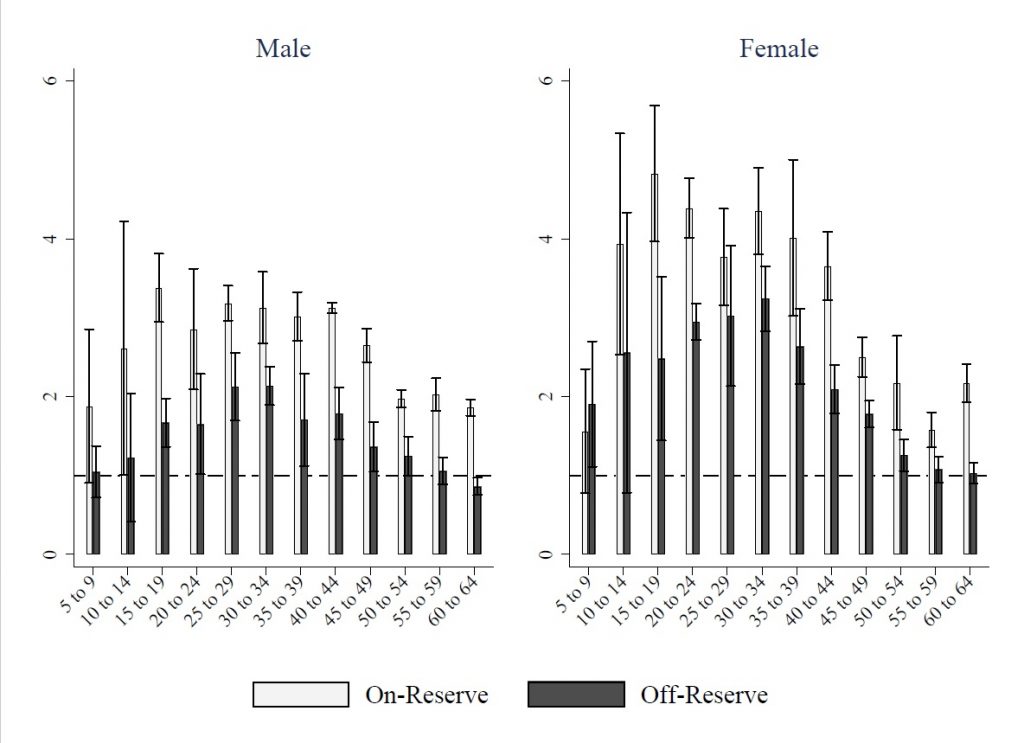

The results were unsettling. While murder is a cause of death that is typically far too rare to observably increase aggregate mortality statistics, we found shockingly high relative mortality rates for Status First Nations women and girls: Status women and girls have mortality rates that are three to four times that of the general female population between the ages of 10 to 44. We also found that mortality rates of Status girls between the ages of 10 to 14 were actually higher than for Status boys of the same age, which is typically not the case for the general population.

In addition, on reserve mortality rates are even more striking: Status First Nations girls between the ages of 15 and 19 are five times more likely to die than girls of this age in the general Canadian population. Status boys of the same age on reserve were four times more likely to die than boys in the general population. Mortality rates are the highest in the prairie provinces of Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan in this time period.

Relative mortality rates (status First Nations mortality rate divided by Canadian average mortality rate) averaged over 2010 to 2013, by place of residence, gender and age.

For us, the most disappointing research finding is that things do not appear to be getting any better: age standardized mortality rates for Status women and girls below the age of 40 have not changed in the past 30 years and may have even increased for some age groups. In addition, there has been no improvement in relative mortality rates on reservation in the past 40 years.

What are the causes of such high rates of mortality and why aren’t things improving? It seems plausible this is due to a confluence of factors: domestic violence, abuse, lack of access to medical care, economic marginalization, and systemic biases that have been unresponsive. If things are to change, concrete answers to these question are needed. We hope that the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls will illuminate some paths forward but this research suggests that we need to think more broadly that direct violence resulting in death. The high mortality rates we observe at young ages are unlikely to be due to murder alone. Research that investigates these broader social factors affecting Indigenous peoples’ life expectancy needs to appreciate the gender nature of Status First Nations mortality in Canada.

First Nations communities and activists have been voicing these concerns for a long period of time (for example the Native Women’s Association of Canada and Amnesty International) and these issues are a concern in North America more broadly. We hope the coming decades will be decades of positive change. Another 40 years of no change is unacceptable.

Read the full article for free until end June 2019, in Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’economique: Feir, D., & Akee, R. (2019), First Peoples lost: Determining the state of status First Nations mortality in Canada using administrative data. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’economique, 52(2): 490-525. doi: 10.1111/caje.12387

About the Author

Dr. Donna Feir is a research economist, with the Center for Indian Country Development (CICD) at the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank and joined the CICD in 2018 after spending four years as an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Victoria. Donna is an applied labor economist and economic historian who has published on reconciliation, modern Indigenous labor market experiences, health, and the impact of historic policies on Indigenous economies and people. Donna is a Research Fellow at the IZA Institute of Labor Economics and member of the Association for Economics Research of Indigenous People. Donna received her Ph. D. from the Vancouver School of Economics at the University of British Columbia.

1530-2415/asset/SPSSI_logo_small.jpg?v=1&s=703d32c0889a30426e5264b94ce9ad387c90c2e0)

1099-0860/asset/NCB_logo.gif?v=1&s=40edfd0d901b2daf894ae7a3b2371eabd628edef)