Honesty is the best policy in healthcare, but how to make it a reality?

In healthcare, as in all walks of life, things go wrong. However, the consequences of an activity going wrong in healthcare can be a matter of life or death. How a healthcare professional and their employer deals with an error is critical to maintain public trust and ensure that a mistake is not repeated. The tragic events of Mid-Staffordshire Foundation Trust and the Hyponatremia related deaths in Northern Ireland have bought into sharp relief the importance of professionals being open and honest, and apologising where appropriate to patients. This is often termed candour. It has focused the minds of policymakers on better understanding barriers to professionals being candid and what more can be done to encourage candour when something goes wrong.

Last month, the Professional Standards Authority (the Authority) published its contribution to the debate: Telling patients the truth when something has gone wrong. This focused greatly on the role of UK professional regulators in embedding candour among healthcare professionals. The paper is based primarily upon:

- Discussion groups with staff of regulators who regulate health care professionals and individuals that work with regulators to judge whether a professional is fit to practise. These discussions were facilitated by Annie Sorbie (Lecturer in Medical Law and Ethics at Edinburgh University)

- Questionnaires from regulators and stakeholders across health and care.

Moving from theory to practice

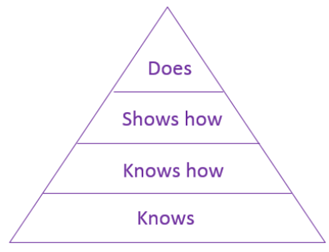

We found that healthcare organisations have made strides to embed candour amongst professionals. However, learning can only take an individual so far. One education stakeholder, referring to Miller’s Pyramid (see below), informed us that it had ‘little doubt’ that medical trainees know (‘knows’ and ‘knows how’) their duty to be candid and can demonstrate competence to adhere to it (‘shows’). However, the, organisation considered that when trying to comply in practice with that duty (‘does’), medical trainees were subject to other pressures such as that created by a blame culture.

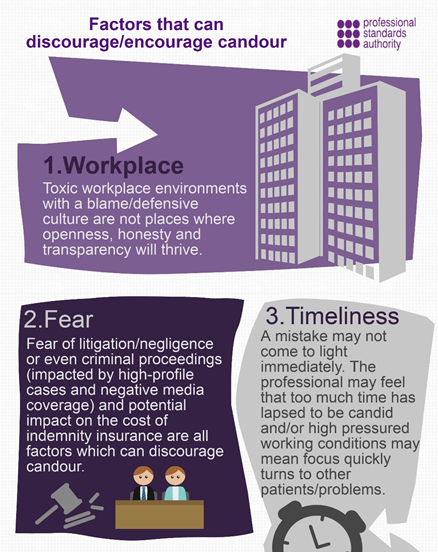

The candour of a professional is seen to be heavily influenced by the culture of their workplace. An organisation with a defensive or blame culture has the potential to isolate professionals who have acted candidly. The word ‘fear’ was often mentioned in stakeholders’ responses: this included fear of litigation, fear of the regulator striking a professional off their register, or fear of public and media perceptions and the ensuing impact on a professional’s livelihood.

One means to make candour a reality is by making case studies available to professionals. Guidance from organisations may not necessarily resonate with professionals whereas the principles of guidance can be reified by case studies. One discussion group participant commented that unless candour was anchored in the realities of professionals’ working lives it risked ‘just becoming another aspirational standard’.

Reframing candour from a negative to a positive approach

When candour is currently discussed it is frequently viewed from the negative vantage point of when a professional is lacking in candour. A significant number of questionnaire respondents and discussion group participants thought there was an opportunity for regulators to focus more on when a professional has been candid to a patient, or ‘positive’ candour. One stakeholder noted ‘it would be counter-productive to emphasise the ‘stick’ of regulatory compliance by trying to place even greater importance on what regulators require when there is a rather more effective ‘carrot’ of educating professionals and explaining that being candid is an important part of their job and central to maintaining a professional relationship with patients’. A reshaping of the way candour is discussed could be useful in encouraging candour and avoid a discourse which is based around complaints and discipline rather than seeing candour as a positive professional attribute.

Sorry seems to be the hardest word to say

An example of positively looking at candour is the act of an apology. Ostensibly it is an act brought about due to an error but an apology can show that a professional empathises with and recognises the impact that an error has on a patient. It has been suggested in other literature that an apology can have ‘profound healing effects’ for professionals as well as patients as it can ‘help diminish feelings of guilt and shame’ in professionals in addition to facilitating forgiveness and create a foundation for reconciliation in patients.[1] One discussion participant talked about how the process of being candid has the capacity to be a ‘cathartic’ experience and can feel like a ‘weight lifted’.

Generally, healthcare professionals are highly trusted by the public. However, trust can evaporate quickly if honesty and openness is lacking. One firm of solicitors noted: ‘Many patients who contact us seeking legal advice regarding a potential negligence claim state that they had previously had a high level of confidence in their doctors (even when things may have gone wrong) but that it disappeared quickly in the absence of openness and honesty regarding their injury’. Our report notes that there may be merit be in seeing candour as contributing to maintenance of public trust in professions. One regulator suggested that there should be ‘encouragement for seeing candour as a professional strength not a cause for concern’. In fact, as one stakeholder observed, an apology can foster ‘mutual trust and respect which forms the bedrock of the professional relationship’.

Humans are fallible, and things go wrong. For many errors, it’s not the mistake that matters; it’s how a professional deals and learns from it, and then applies that lesson into practice. Most patients expect nothing less than honesty when something goes wrong. An apology can go some way to nurturing trust in professionals and evidence that something will be done to not repeat the mistake. Candour needs to move beyond simply something that is an ideal accepted by many but often unattainable, to a value which is put into practice by all health professionals when something goes wrong. Positive perceptions of candour, blame-free work environments and relatable guidance examples may go some way to translating policy aspirations to practice action.

[1] MacDonald, N and Attaran, A. (2009). Medical errors, apologies and apology laws, Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Michael Warren is a Policy Adviser at the Professional Standards Authority, London, UK

www.professionalstandards.org.uk