“Was DACA Responsible for the Surge in Unaccompanied Minors on the Southern Border?”

Large steel fence protecting the border between Mexico and the United States of America at the Tinajas Altas Mountains in Arizona (Sonoran Desert). Shutterstock ID 141374191; Reference: 9780730333005

The decision by the US administration to repeal the Executive Order of the Obama administration, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), has caused a great deal of commentary. This brief statement originally published in the journal International Migration elaborates on the findings reported in our original article (free to access until 9th December).

On September 5, 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the Trump Administration would end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program – a program implemented by President Barack Obama via executive order on June 15, 2012. The program granted two-year reprieves from deportation to undocumented immigrants brought to the United States as children –the so-called Dreamers. In his remarks, Senator Sessions noted that:

“The effect of this unilateral executive amnesty, among other things, contributed to a surge of unaccompanied minors on the southern border that yielded terrible humanitarian consequences.”

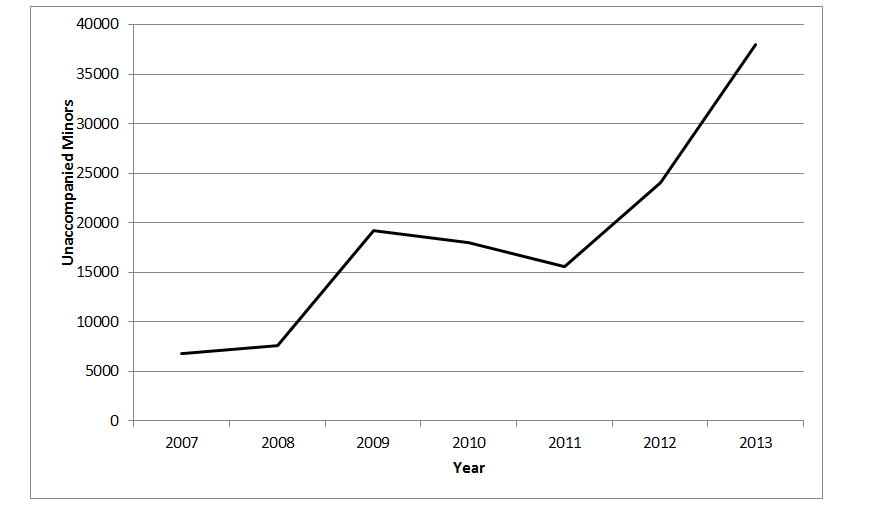

Yet, what evidence do we have to support that claim? Using data on apprehensions of unaccompanied children by border patrol sector, nationality and year,[1] we looked into that question and explored the determinants behind the increase in inflows of unaccompanied alien children from Central America. To start, we plotted the data on unaccompanied minor apprehensions over the 2007 through 2013 period. The number was at its lowest prior to the enactment of the 2008 Williams Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA).[2] It then doubled during 2008-2011 period, following the implementation of the TVPRA and prior to the announcement of DACA. While the increase might have suggested that the TVPRA played a role, the number of apprehensions doubled again during 2012 and 2013. This last spur contributed to the belief by some that DACA was behind the growth in the flows, even though unaccompanied minors were not eligible for the reprieve offered by DACA.

Figure 1: Apprehensions of Unaccompanied Minors

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) via a Freedom of Information Act request.

The above Figure 1 is from our original article and is purely descriptive and fails to account for the myriad of factors that could be contributing simultaneously to the observed changes in unaccompanied minor flows. A more thorough examination of the unaccompanied flows requires accounting for other factors potentially responsible for the observed changes in unaccompanied minor apprehensions. We thus paid special attention to the effect that DACA, along with the enactment of the TVPRA, played on the surge of unaccompanied minors originating from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras in recent years. We also controlled for a number of country-specific push factors, as well as traditional pull factors. These included homicide counts and real GDP per capita of the sending countries, as well as real U.S. median weekly earnings, U.S. unemployment rates, the number of lawful permanent residents admitted from each country of origin and the number of border patrol agents by sector along the southwest border of the United States and Mexico.

The analysis revealed that DACA did not significantly contribute to the observed increase in unaccompanied minors. Rather, the TVPRA, along with violence in the originating countries and economic conditions both in the origin countries and the United States, emerged as some of the key determinants of the recent surge in unaccompanied minors apprehended along the southwest U.S.-Mexico border.

Given the significant impact that revoking DACA has on approximately 800,000 lives, getting the facts about DACA straight is imperative and a moral obligation to the youth who trusted the government when registering for the program.

Footnotes

[1] While the number of apprehended youth is not the ideal measure of the number of unaccompanied minors who have successfully crossed into the United States, the two are likely to be correlated given the generalized practice of turning themselves in to the border patrol agents upon crossing (e.g. American Immigration Council 2014, Preston 2014).

[2] The TVPR legislated that unaccompanied minors from non-contiguous countries needed to be released into the custody of family or sponsors while they await a deportation hearing in front of a judge; thus enabling children to stay in the United States for what became, in most instances, years.

References

American Immigration Council. 2014. Children in Danger: A Guide to the Humanitarian Crisis at the Border. Special Report, July. Washington DC. Available at: http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/docs/children_in_danger_a_guide_to_the_humanitarian_challenge_at_the_border_final.pdf [Last accessed on July 20, 2015].

Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina and Thitima Puttitanun. 2016. “DACA and the Surge in Unaccompanied Minors at the U.S.-Mexico Border,” International Migration, Vol.54, Issue 4, pp.102-117. doi:10.1111/imig.12250.

Preston, Julia. 2014. “Migrants Flow in South Texas, as Do Rumors” The New York Times. Published June 16, 2014. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/17/us/migrants-flow-in-south-texas-as-do-rumors.html [Last accessed on September 8, 2017].