Care equity and the welfare state in Japan: Contextualizing what the child protection system seeks to safeguard

The child abuse crisis:

Japan has a lively arena of research on children’s social care. Yet, there has been relatively little attention given to social constructions of childhood, abuse, and other pressing topics of debate, particularly in relation to structural and cross-cultural contexts. This is interesting considering how widespread visual and discursive representations of child abuse have proliferated throughout Japan in the past 30 years.

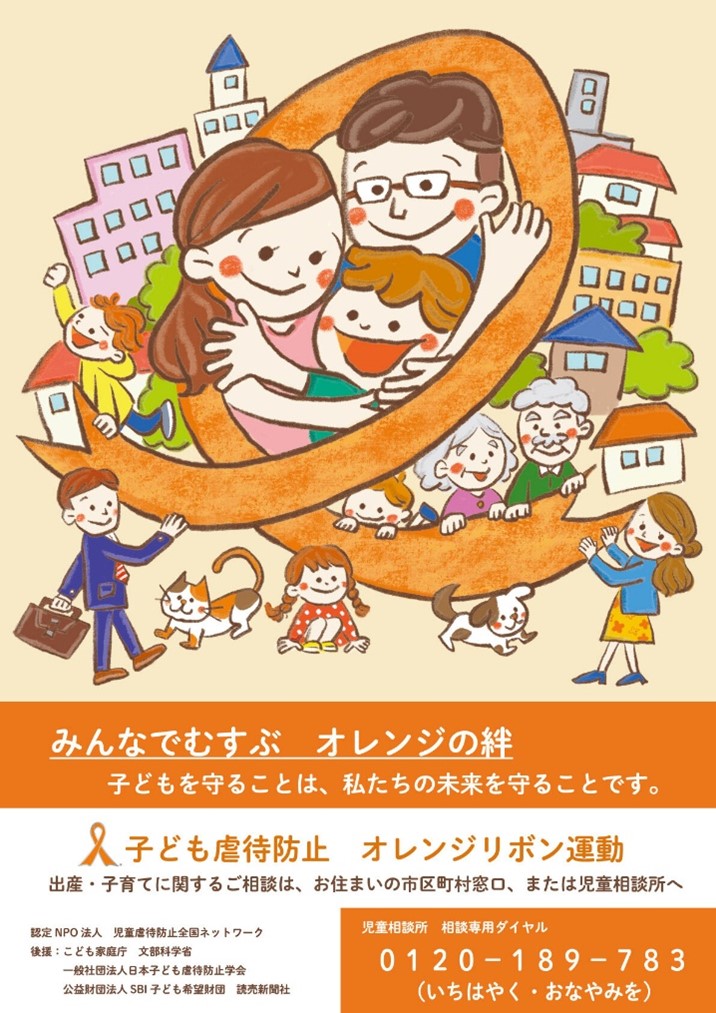

I recently wrote a paper on the social-cultural construction of child abuse and its possible consequences on casework practice and national statistics (Chapman, 2024b). Since the mid-1990s, the annual number of child abuse reports made to child protection authorities in Japan has surged, bringing policymakers and practitioners into a difficult situation: How do we respond? Since the early 2000s, the child protection system has re-attuned its attention to responding to child abuse reports by staffing more caseworkers and hiring health professionals to support abused and neglected children. The national government has also given this issue a visual brand: an orange ribbon symbolizing child abuse awareness and prevention. This ribbon is featured in visual media, such as the poster above. Both the increased presence of caseworkers and vigilant citizens have crafted a distinctive field of visual-discursive representations of child abuse and children (Hacking, 2001:57-60).

The complicated outcome I suggested is that community awareness of a socially mediated issue—child abuse—has resulted in immense pressure on the state to act. This is notable because Japan’s child protection system follows what other scholars have coined the ‘East Asian welfare model,’ a minimalist welfare model that places the responsibility of care on the family and community—what we could call a ‘welfare society’ (Aspalter, 2006; Chapman, 2024a). The family envisioned by the child protection system is a normative ideal, the nuclear family model. Yet, social disruptions throughout the past thirty years, from economic slumps and precarious labor markets to pressures from a greying population, have shifted normative expectations around family life into aspirations more than possibilities. All this said, most child abuse investigations result in consultations; very few children, relatively speaking, are brought into alternative care. Yet, child abuse reports continue to rise, putting more strain on caseworkers and state services, a system whose ethic of care affixes the nuclear family, self-reliance, and the family bond as matters of safeguarding and cultivation. These representations of family in turn have become standards by which non-normativity is scrutinized and evaluated, shaping a complicated social space that may contribute to child abuse metrics as well as maintain the precarious but enduring placement of welfare responsibility on the family and community.

Child non-normativity and the welfare state/society:

Alongside child abuse, disability is another key issue that child protection authorities in Japan are keen to improve their response to especially as state casework agencies employ increasing numbers of health professionals. As a companion to the article above, I offer supplementary commentary on childhood normativity and the welfare state to continue a scholarly dialogue on the social-cultural dimensions of caregiving and well-being. Disability, like child abuse, is crossing social and medical registers, and while encapsulated within a technical field, has become widespread among both the public and child protection authorities (Hacking, 1995: 359). It is important to note that disability has a history of stigmatization in Japan. Child protection authorities I spoke with reported that they consider disability as a condition that needs long-term support, like child abuse and neglect. Concepts like Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), have taken root in child protection discourse, although I also interviewed caseworkers who found the concept to be potentially problematic in its deterministic assumptions. Furthermore, disability is a risk factor that may lead authorities to alternative care arrangements depending on a family’s living situation and resources. However, children’s perspectives are often absent from these decision-making processes, including investigations and casework judgments. This is not to imply that including children’s participation is a panacea, but that their participation could provide new care opportunities and transparency for stakeholders, ultimately helping to promote care equity. The current support landscape and mixing of social-medical fields suggest an interesting situation: the ethos of child protection may index an able child as normative. That is, orange ribbon imagery and casework caricatures portray children with non-normative bodies and behaviors as socially and medically deviant. If disability and the negative effects of abuse are matters that might benefit from long-term care, then what exactly is the relationship between a minimalist welfare service model and the family institution when skilled care might be valuable? The aforementioned paper I authored begins a conversation in response to this broad question.

The familial-by-design ethic of social care services and state attention may complicate the medicalization of children as community-based organizations continue to introduce novel but niche social programs. The neoliberalization of child protection may produce inequities, however, as questions of accessibility, parity, and longevity mark the landscape of social welfare capitalism. Japan’s alternative care system, for reference, operates close to 600 privately managed child protection institutions, a number that also includes specialized institutions for skilled care needs, ranging from psychiatric therapeutic care to controlled spaces for youth in the criminal justice system. These institutions are often managed under social welfare corporations. Most children who enter care are placed in residential group homes. Variations in and the decentralization of the system may impact how social-medical perceptions of disabled children are circulated and mediated. It may be that the discourse on child abuse and its representations of kinship normativity have facilitated the state’s surveillance of disability, leading to complex questions of welfare responsibility and care needs. The normalization of the (nuclear) family bond in child protection aligns well with Alison Kafer’s (2013, 27-28) statement on disability, that the state cannot conceive of social non-normativity without intervention and correction. Investigating these processes, nevertheless, is an important step in addressing care inequity. In the case of children’s social care in Japan, along with other neoliberal, family-first welfare systems, it may be worthwhile to rethink the rigid boundaries between the state, its agents, and families to facilitate more relational understandings of social care that account for upstream factors and broader structural contexts.

You can read about this topic in more detail in the academic article published in Children & Society: Chapman, C. (2024). “The Orange Ribbon and the Pitiful Child: Investigating Child Abuse, Family Normativity, and the Welfare State in Japan.” Children & Society. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12934

References:

Aspalter, C. (2006). The East Asian welfare model. International Journal of Social Welfare, 15(4), 290-301.

Chapman, C. (2024a). “Dissonances in Care: Childhood, Well-being, and the Politics of Welfare in Japan.” Thesis. University of Oxford.

Chapman, C. (2024b). “The Orange Ribbon and the Pitiful Child: Investigating Child Abuse, Family Normativity, and the Welfare State in Japan.” Children & Society, 0, 1-11.

Hacking, I. (1995). The looping effects of human kinds. In D. Sperber, D. Premack, and A.J. Premack (Eds), Causal Cognition: A Multidisciplinary Approach (pp. 351-83). Oxford: University Press.

Hacking, I. (2001). Rewriting the Soul: Multiple Personality and the Sciences of Memory. Princeton: University Press.

Kafer, A. (2013). Feminist, Queer, Crip. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

1475-682X/asset/akdkey.jpg?v=1&s=eef6c6a27a6d15977bc8f9cc0c7bc7fbe54a32de)