Against the Imperial Incorporation of Asian Americans

In this blog, Harleen Kaur and Victoria Tran share the process behind their recent Sociology Compass publication, which analyzes and offers alternatives to current sociological frameworks of studying Asian Americans.

Our collaboration began like many pandemic ones – in a private chat on Zoom. Both students in the UCLA Sociology doctoral program and enrolled in Professor Karida Brown’s inaugural Du Boisian Sociology course, we quickly found common ground in applying Du Boisian methodologies & theories to our research around Asian American subject formation. Specifically, our rapid back-and-forth began after reading Du Bois’s remarks in his 1920 literary work, Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil, on the indoctrination of the US-bound migrant:

“[America] trains her immigrants to this despising of ‘n*****s’ from the day of their landing, and they carry and send the news back to the submerged classes in the fatherlands (51).”

This stark yet relevant commentary on the globalization of the racial contract allowed us to contextualize our shared interest in mapping Asian American communities’ strategic navigation of white supremacist racism. In the fall of 2020, as we dove deep into Du Bois’s oeuvre, Asian Americans were already increasingly at the center of mass violence. Earlier that year was the 2020 Atlanta spa shootings, in which east Asian women were the primary victims, alongside broader pandemic-related anti-Asian sentiment throughout 2020. This was quickly followed by the 2021 Indianapolis FedEx facility shooting, where Sikh Punjabis are predominantly employed and thus were half of the deceased. Resulting conflict within Asian American community organizations around new hate crime bills pitted grassroots organizers against larger-budgeted civil rights non-profits; the former cites the inevitable harm of these bills on Black and brown communities, while the latter calls for increased representation in the US police and military to establish greater safety and belonging for Asian American communities.

Meanwhile, as we worked on our respective dissertations, we struggled to find sociological literature that did not limit the subject formation of our community interlocutors. Engaging with current sociological frameworks on Asian Americans in our coursework, from race and ethnicity to migration, we repeatedly came up against one clear assumption: sociologists’ underlying assumption that incorporation is the natural end goal of migration. Rather than analyzing pro-state politics as constructed through centuries of imperialism in countries of origin and forced assimilation through white supremacist inclusion, incorporation was unproblematically positioned as the unique culmination of settlement in the US. At the same time, exchanging anecdotes from our fieldwork, we soon realized our communities of research and upbringing (Vietnamese & Sikh Punjabi) shared remarkably similar political and social attachments to serving in the US military as a primary tactic of belonging in the US.

Since the first major wave of Asian migration to the US two centuries ago, there have been several shifts in how Asians have been imagined, and imagined themselves, as part of the nation-state. The import of Chinese and south Asian indentured labor throughout the 19th century initially grew from the need to suppress slave rebellions in the southeastern US, and then to address increasing labor costs after the US’s legal abolition of chattel slavery (the actual practice would last until 1865 at least). Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, selective citizenship incorporation policies continuously recalibrated Asian subjectivities to uphold racial capitalism and settler-colonialism central to the development of the US. While no longer fueling plantation-style labor, continued Asian American labor through westward railroad expansion created the economic, political, and social conditions to expand US settler-colonialism and deny Indigenous sovereignty. As the US continued its imperial expansion in the Pacific Islands and southeast Asia through multiple World Wars, military service also became a means to separate Asian Americans who were worthy of citizenship with those to be viewed with suspicion and incarceration.

Such dual-trajectory subject formation might have continued if not for the engagement of diasporic Asian students in the collective social and political upheaval of the mid-twentieth century US. UC Berkeley graduate students Emma Gee and Yuji Ichioka coined the term “Asian American” in 1968 during student strikes for Ethnic Studies. Subsequently, Asian American became a social category to group diasporic groups experiencing similar racialization and ostracization in the US, albeit with questions about its accuracy. Still, the term took hold nationally as an organizing mechanism against the US war in Vietnam. While Asian American military allegiance had originally allowed such communities to gain economic and social standing at the expense of Black and Indigenous populations, 1960s-era Asian American activists forged pan-ethnic alliances and transnational sympathies linking US imperialism abroad to their experiences of racist inequality domestically. Yet, these anti-imperial politics are not as obvious in diasporic politics today. Contemporary US Sikh organizations prioritize Sikh legacies of British imperial service to advocate for inclusion in the US police and military. Second-generation Vietnamese Americans use ancestral legacies of US military service to justify their own enlistment and their support for US military intervention in Afghanistan. Engaging such contemporary political and social attachments, our paper contends with Asian Americans’ ongoing relationship with imperialism through military service, to the extent that it has become a primary site of relationality with the US.

Knowing the stakes of Asian pro-state sentiments, which continue to manifest as desires for increased military and police service despite the historic and present harms against these same communities, we were compelled to intervene in sociological frameworks of Asian American-US state relationalities which fail to contextualize the long histories of Asian incorporation into the state. Building on race and racism frameworks that emphasize such global, historical, and colonial dimensions of race relations, our paper offers an anti-imperial theoretical framework for studies on the color line and global geopolitics. Reconceptualizing colonial histories alongside contemporary subject formation, we problematize incorporation into the US, specifically via its military apparatus, as a strategic response to racial and economic precarity. As an alternative to current scholarship, we understand the selective incorporation of “good” immigrants as further bolstering the state’s imperial forces for extracting and maintaining capital rather than an act of American benevolence. While existing discussions problematize the homogenized approach to studying Asian American communities or, at best, a homogenized sub-community study, we complicate such approaches by using a parenthetical in Asian (American) to indicate when we are discussing the process of becoming Asian American – an intentional push against a universalized Asian American category (discussed without parentheses) and a reclaiming of alternative subjects that can form in the process of settlement from Asia to the US.

The paper offers an overview of existing sociological frameworks on Asian Americans and a new framework of “Extinguishing Asian (American) Insurgency” through an analysis of two transnational, but US-based, case studies: (1) Sikh political radicalization through the anti-colonial Gadar Party and (2) US state efforts to tie diasporic South Vietnamese identity to an anti-communist politic. Through these case studies, we demonstrate how scholarly depictions of Asian American subject formation legitimate imperialism as the sole natural producer of relationality between the US and Asian American communities. For US-based Sikh Punjabis, British racial ideologies around cultural predisposition for military service facilitated contemporary incorporation through an ongoing attachment to US imperialism. For South Vietnamese refugees, conceptualizing the war as a benevolent intervention sutured the diasporic community to ongoing US imperial efforts by producing a culture of grateful refugees paying back dues to the country that rescued them. In both instances, due to US state policy to incorporate Asians via military service, Asian (American) insurgency has been obscured as a viable subject formation. The exploration of US surveillance, imperialism, and militarization through the case studies also shows how crucial the active policing of Asian (American) insurgency has been to upholding US imperialism.

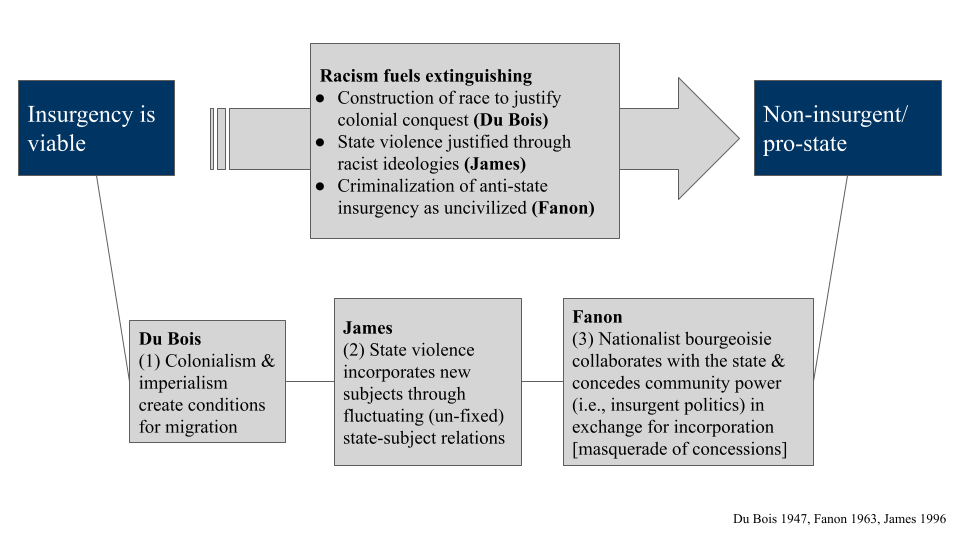

Our framework, Extinguishing Asian (American) Insurgency [Figure 1], brings together W.E.B. Du Bois, Joy James, and Frantz Fanon to explore how scholarly depictions of subjugated communities transform from insurgent possibilities to largely pro-state. We pose three questions to guide contemporary and future research on the various possibilities of Asian (American) subjectivities:

- Through W.E.B. Du Bois, how did colonial and imperial relations motivate migration?;

- through Joy James, how does the state use violence as a mechanism of diasporic incorporation?; and

- through Frantz Fanon, how and why do certain members of the community collaborate with the state?

More importantly, it demonstrates the role of the state, through imperialism, as motivating the extinguishing of possible insurgent politics (extinguishing as self-inflicted or state-induced). Last, it shows how such political transformation is done through the construction of a nationalist bourgeoisie in Asian (American) communities, who drive the negotiating of new relationalities with the state. Without a critical analysis of postcolonial subject formation, it is possible to emerge with a homogenized focus on nationalist bourgeoisie groups within the Asian (American) community who uphold colonial forms of domination to ensure their economic, political, and social gains, as much of mainstream sociology has done. Instead, a sociological incorporation of imperial-colonial studies allows us to better trace how subject formation has been constituted by the needs of empire and conditions around the state’s migrant incorporation. For Asian (American) subjects, whose conditions for migration to imperial lands were shaped by the state’s economic and political needs, a transnational analysis of racism clarifies contemporary pathways of incorporation.

In relocating insurgent Asian (Americans) in sociological scholarship, we argue that Asian insurgency demonstrates the capacious possibilities of understanding the particularities of violences while also acknowledging shared experiences of colonization. Incorporating postcolonial theory and global histories to the study of Asian diasporic groups allows us to analyze how empire shaped racism in a way that does not treat these relations as natural, but still significant for understanding material realities and possibilities for coalition. Future scholarship can use Extinguishing Asian (American) Insurgency to bring out the role of the US in co-opting narratives of Asian (American) insurgency, such as depicting Japanese internment during WWII as an example of patriotic nationalism while minimizing the role of Japanese American draft resisters as an insurgent movement, or in analyzing how overlapping Spanish and US imperial histories in the Philippines and Guam have resulted in both illegible projects of racial and state incorporation for these diasporic communities. Understanding that Asian devotion to the state has directly and indirectly legitimized the US as an imperial power, we challenge future scholarship to not take these pro-state relations for granted and more rigorously incorporate a Du Boisian framework of a global color line constructed through histories of colonization and imperialism.

Kaur, H., & Tran, V. (2023). The limits of imperial incorporation: Alternative sociological frameworks to study Asian American subjects. Sociology Compass, e13069. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.13069

Authors

Harleen Kaur, Arizona State University, United States

Victoria Tran, University of California, United States

1754-9469/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=9197a1a6ba8c381665ecbf311eae8aca348fe8aa)