A Covid Cry: adjusting, adapting & extending

by Bethan Prosser · Published · Updated

Last night (11th November) the UKRI announced their latest position on funding extensions for PGRs, and I burst into tears. As I tried to grasp the fine print detail of the UKRI statement, my eyes kept leaking out fear and hopelessness. Will I be one of the lucky ones? Does my end date fit? Have my circumstances been challenging enough? How can I finish this project before the money runs out? What else is going to happen to the people I love around me before I even get to that point? How will I keep it together?

Last night (11th November) the UKRI announced their latest position on funding extensions for PGRs, and I burst into tears. As I tried to grasp the fine print detail of the UKRI statement, my eyes kept leaking out fear and hopelessness. Will I be one of the lucky ones? Does my end date fit? Have my circumstances been challenging enough? How can I finish this project before the money runs out? What else is going to happen to the people I love around me before I even get to that point? How will I keep it together?

This morning, bleary eyed, I’m trying to make sense of it. This morning I’ve realised that even without sorting and cataloguing the anxiety, pain and disruption of the last 9 months, my project has become extended. Even without considering the uncertainty of the coming months, as loved ones grapple with Covid-induced long-term illness and financial precarity and restrictions come and go, my project has become extended.

In UKRI terms, I have adjusted my project successfully. I have adapted, innovated and developed new methods. But as I attempt to positively claim this new territory and write my methodology, it’s critical to understand all the methodological manoeuvres and twisting of time it’s taken to get here. The term ‘digital pivot’ does not adequately capture the Covid-induced myriad of movements. Not revolving cogs in a well-oiled machine, nor gentle ripples undulating outwards, nor an evenly paced lines of dominoes neatly falling. These spinning, whirling, swiveling, gyrating goings-on are something else. To get a handle on this process, I have tried to distill these into sets of movements, a tale in four parts, as I ask exactly what has taken up my time?

Movement#1: Re-calibrating and re-thinking

When this first hit, I felt lampooned by lockdown. What did my project matter when the world was ending? But as my imagination moved from playing out apocalyptic film scenarios to the realisation of the quiet mundanity of lockdown PhD life, my brain started to re-approach my topic of urban seaside gentrification. What happens to gentrifying processes in crisis? How is the seaside re-constituted during a health pandemic? How does restricted mobility bring people’s relationship to their neighbourhoods into sharp focus? I was struck by both the privilege and responsibility of being funded to carry out research at this time.

Walking around my own neighbourhood, these questions and thoughts began to simmer and stew. It was important to capture this moment, and many others felt the same as ways of recording, expressing and processing pandemic experiences started to explode online. Being a researcher suddenly felt important. But how could I go about it, what else could I add?

Movement#2: Re-visiting and re-sounding methods

The pandemic had struck me off my path of using sound and mobile methods to explore changing seaside neighbourhoods. I had spent a year experimenting with group soundwalks as a way of generating discussion and reflections on people’s sense of place. I had become enamoured with the in-situ-ness of mobile methods and smitten with soundwalking as a ‘spatio-temporal, embodied, situated, multi-sensory and mobile practice’ (Behrendt, 2018:252). But with no possibility of travelling to my sites or meeting with residents, what could be done?

During my re-calibration, I had made daily audio recordings for a month. The dramatic changes in soundscapes during lockdown have been frequently commented on. Our altered acoustic environments have been integral to our heightened awareness of our immediate surroundings.

And so I realised my way forwards. There were so many ways of doing soundwalks, facilitating listening and using elicitation techniques. It was now a case of re-visiting these tools to make them work remotely and online.

Movement#3: Embracing the remote & digital

Covid-19 demanded I part ways with certain cherished foundations of my methodology, namely, I could no longer spend physical time in my sites or with others.

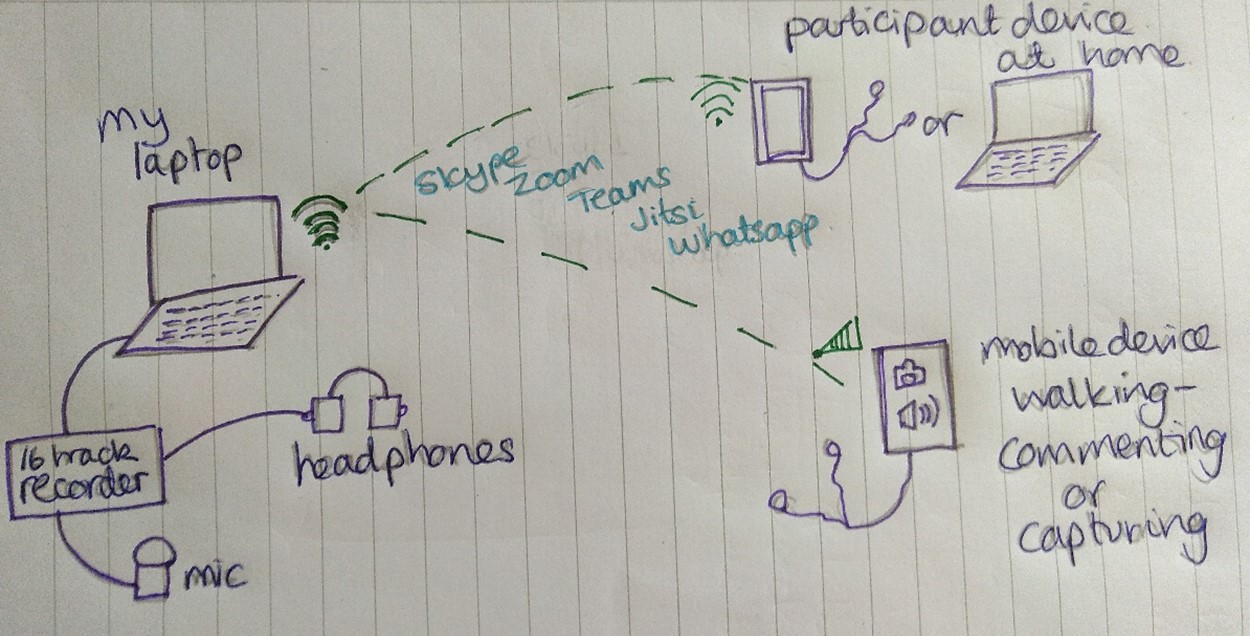

Becoming removed, I identified two central remaining components: listening and elicitation. I realised there was no reason why residents could not do listening walks or activities on their own. The key challenge was then how to capture this meaningfully, effectively and accessibly. There are many uses of mobile technologies, especially within mobile methods, however conscious of digital exclusions, I wanted something that was as flexible to people’s circumstances as possible.

Image 1: Drawing of my technology

Learning, scoping and reviewing all the technological possibilities was exhausting, ate time and has ongoing repercussions. Previously technology was implicit and seemingly commonplace in my methods e.g. a recorder in interviews or a laptop for writing. Now technology is a diva screaming out for attention and demanding new areas of literature to be charted.

Movement#4: Piloting & recruiting

Once I had conquered the equipment and software, or at least had cobbled together a configuration I felt comfortable with, I was ready to test it out. I am ever grateful to the three postgraduates who volunteered to test this out with me. It was invaluable time spent, preparing, revising paperwork and addressing new ethical dimensions brought about by the technology and the ever-present risk of the coronavirus.

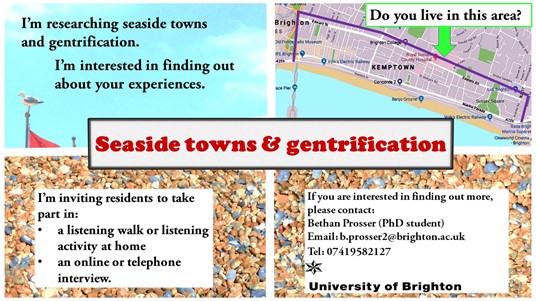

Experimenting and digesting, I had eventually arrived at a new method: remotely guided listening walks and listening activities at home with participant-captured observations followed by elicitation interviews via telephone or video conferencing. But I was not there yet, after three months of re-thinking, re-visiting methods, reviewing technology and piloting, I was left with the challenge of how to recruit seaside residents. This required yet more adjustments, redesigning recruitment materials and finding new online networks through which to recruit.

Image 2: Digital recruitment flyer

Next movements: extending and extenuating

These four movements can be roughly equated to three months additional and unanticipated work. Fortunately, this time was well spent. I have so far worked with 22 seaside inhabitants and generated a wealth of rich fine-grained material, which I feel is comparable to any material I could have generated in-situ. Seaside residents have welcomed the opportunity to sonically explore and reflect on their homes and their neighbourhoods through spring lockdown, summer easing and renewed autumn restrictions.

Reflecting back and grouping these manoeuvres has helped me work through the de-motivating recent announcements on funding extensions. But there is still much more work to be done, to successfully complete the project I was recruited for and am being paid to do. The outpouring on social media and pressure mounting from groups such as Pandemic PGRs shows I am not alone in my anger and frustration at the apparent lack of understanding of how covid has twisted and tormented our PhD journeys. But time will tell if my own PhD story will be granted the requisite time to reach a ‘happily ever after’ ending.

References

Behrendt, F. (2018). Soundwalking. In M. Bull (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to Sound Studies Routledge.

Bethan Prosser is a doctoral student researching urban seaside gentrification and UK south coast residents’ experiences of displacement. She has a background in migration studies, philosophy and politics combined with professional experience working in the community voluntary sector and brokering community-university partnerships. She is currently funded by the ESRC South Coast Doctoral Training Partnership at the University of Brighton.

https://research.brighton.ac.uk/en/persons/bethan-prosser

1540-6210/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=812a48e1b22880cc84f94f210b57b44da3ec16f9)