The 40th Anniversary of the Violence at Kent State – a gap in our historical memory?

Today is the 40th anniversary of the Kent State shootings. Not long ago, I looked out at my large section of a social problems course and asked if anyone could explain the events that took place at Kent State on May 4th, 1970. I wondered, in the silence following, how a lack of knowledge about this tragedy could exist. I rephrased my question…to no avail. This event is part of American History and is taught as such. And yet, when I think about my own education, I do not remember the lesson – was I absent on this day in middle school? Did all the students in my social problems class miss the same lesson? This led me to a question I often ask: Why do we remember certain historical events and not others? As this subject is the focus of many cognitive sociological studies of collective memory, it seems fitting to pose this question on a day like today. Why is Pearl Harbor something that most students can at least briefly describe and yet Kent State is not? Further (as the rather excellent NPR piece listed below reports) why would those who know about Kent State be much less likely to know about another similar event at Jackson State in Mississippi, which took place just over a week after the events in Ohio?

Today is the 40th anniversary of the Kent State shootings. Not long ago, I looked out at my large section of a social problems course and asked if anyone could explain the events that took place at Kent State on May 4th, 1970. I wondered, in the silence following, how a lack of knowledge about this tragedy could exist. I rephrased my question…to no avail. This event is part of American History and is taught as such. And yet, when I think about my own education, I do not remember the lesson – was I absent on this day in middle school? Did all the students in my social problems class miss the same lesson? This led me to a question I often ask: Why do we remember certain historical events and not others? As this subject is the focus of many cognitive sociological studies of collective memory, it seems fitting to pose this question on a day like today. Why is Pearl Harbor something that most students can at least briefly describe and yet Kent State is not? Further (as the rather excellent NPR piece listed below reports) why would those who know about Kent State be much less likely to know about another similar event at Jackson State in Mississippi, which took place just over a week after the events in Ohio?

Perhaps there is some sort of cohort effect in not knowing about Kent State; students in my classes generally know what happened at  Columbine High. Though they were quite young in the 1990’s, it is possible that Columbine is closer to reality for them. Or maybe this generation is more afraid of each other than of the armed forces. Perhaps protests of the Vietnam War are just too removed from the collective conscience of the current generation or the last few, for that matter. Or, further, maybe this kind of protest seems a relic from the mid 1900’s and irrelevant. There are plenty of other possibilities, but one way of looking at this is through the general lens of cognitive sociology, which suggests that certain events, identities, etc. are marked, while others are not. After all, the events at Jackson State are recalled much less frequently even among those who recall the Kent State atrocity all too clearly, so it cannot all be about generations or relevance. Additionally, certain events are lumped together (as in events pertaining to the Vietnam War – in this category, the events at Kent State could blend into the category overall and be easily forgotten) and then split from other events (such as Columbine or Virginia Tech, which are seen as more relevant, at least in part because they seem within the range of possibility in the current time). Cognitive sociology and in particular, the discussion of collective memory, marking, classification and perception can help us gain greater insight into why some things “matter” historically and others do not. The piece by Brekhus et al below provides a lovely summary of the contribution of cognitive sociology. While the subject of the article is the contributions cognitive sociology can make to sociological studies of race, it can easily be extrapolated to a wide range of topics. Certainly, one possibility as to why Kent State is more prevalent in the American consciousness is precisely because race relations were more tense at Jackson State. The violence in Mississippi was perceived as at least partly motivated by race (which was not the dominant theme of the events at Kent State) and therefore could have been relegated to a less salient spot in the national consciousness.

Columbine High. Though they were quite young in the 1990’s, it is possible that Columbine is closer to reality for them. Or maybe this generation is more afraid of each other than of the armed forces. Perhaps protests of the Vietnam War are just too removed from the collective conscience of the current generation or the last few, for that matter. Or, further, maybe this kind of protest seems a relic from the mid 1900’s and irrelevant. There are plenty of other possibilities, but one way of looking at this is through the general lens of cognitive sociology, which suggests that certain events, identities, etc. are marked, while others are not. After all, the events at Jackson State are recalled much less frequently even among those who recall the Kent State atrocity all too clearly, so it cannot all be about generations or relevance. Additionally, certain events are lumped together (as in events pertaining to the Vietnam War – in this category, the events at Kent State could blend into the category overall and be easily forgotten) and then split from other events (such as Columbine or Virginia Tech, which are seen as more relevant, at least in part because they seem within the range of possibility in the current time). Cognitive sociology and in particular, the discussion of collective memory, marking, classification and perception can help us gain greater insight into why some things “matter” historically and others do not. The piece by Brekhus et al below provides a lovely summary of the contribution of cognitive sociology. While the subject of the article is the contributions cognitive sociology can make to sociological studies of race, it can easily be extrapolated to a wide range of topics. Certainly, one possibility as to why Kent State is more prevalent in the American consciousness is precisely because race relations were more tense at Jackson State. The violence in Mississippi was perceived as at least partly motivated by race (which was not the dominant theme of the events at Kent State) and therefore could have been relegated to a less salient spot in the national consciousness.

Beyond theory, it seems frightening that we could collectively forget an event such as one in which students at a university were murdered. We can also learn a lesson about the importance of making history relevant for students so they will (hopefully) not forget other important moments in both American and global history.

![]() On the Contributions of Cognitive Sociology to the Sociological Study of Race, Brekhus et al.

On the Contributions of Cognitive Sociology to the Sociological Study of Race, Brekhus et al.

![]() Shots Still Reverberate for Survivors of Kent State, Noah Adams, NPR

Shots Still Reverberate for Survivors of Kent State, Noah Adams, NPR

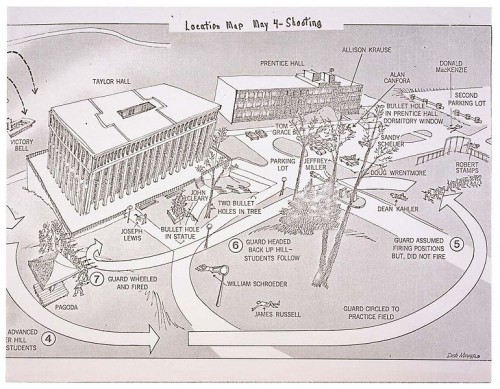

Images in this piece are thanks to the National Archives and Records Administration

My response is to Dena’s question of, “Why do we remember certain historical events and not others?”

There is an age-old saying that “History is written by the winners.” In the case of Kent State, the Vietnam War was the driving force behind the protests across the country. Throughout the War, however, it was clear that America was losing, which is why we eventually left Vietnam to govern itself. Part of the reason that many do not remember an event such as Kent State is because of the very fact that we lost. No student wants to hear about how accurate all of the protestors were in opposing a war–young students like to hear that their country is invincible and mighty, building a sense of patriotism and developing nationalism. Additionally, students that are taking history classes are often ill equipped for meaningful discussions such as politics and motives. If the issue of Kent State were to ever surface, one of the obvious questions is, “Well, why was America in Vietnam to begin with? Why did America feel the need to intervene in another country’s affairs?” When even historians and politicians can’t successfully answer that question, why would we burden youth with having to deal with such heavy topics?

I also believe another key force in why we don’t hear much about Kent State is simply the scope of history. It is an inevitable fact that history will always be increasing in its scope–time, after all, does keep progressing. With currently over 400 years of US history alone to cover, there are more important things that classes can focus on in the limited time they have. Dena brought up the issue of Pearl Harbor; where these two instances differ is that Pearl Harbor was a major factor in getting the United States into World War 2. Someone came and attacked our country–how would we respond? In the instance of Kent State, it was Americans speaking out about us attacking another country–nowhere near as grand an act.

Personally I think we remember certain events more-so than others because oh how the greater society views and remembers them. If you take Pearl Harbor, each and every year elementary school kids have special lesson plans due to the tragic day in our history. It causes an imprint in their minds that resurfaces over and over and over again. What happened at Kent State is not nationally “taught” like the start of WWII for America. I really think that our education system is to blame for what gets remembered and what doesn’t. People are going to remember repetition.

Now, I am in no way saying the events of Kent State are nothing to worry about. The lives taken from the world that day should always be remembered and honored. Any time American lose their lives by the hands of wrongdoers, all of America should pay their respects.

In a final statement I want to add this last thought that came in to my head. The events that have become so remembered throughout our history all seem to be either the culmination of something or the beginning of something. Some events, such as Kent State, seemingly just happened. Nothing huge before. Nothing huge after.

As someone who was born in 1987, I know I never learned about Kent State in school; in fact, I’m pretty sure my knowledge about the event comes from some research I did after hearing the Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young song “Ohio” that describes it.

I think all of you make interesting points. I agree that events that are the “start” of something are remembered more often as they are contextualized, synthesized into a larger historical narrative. However, I also think it’s important that we realize that we also create starting points, just as we create history more generally. The notion, for instance, that Pearl Harbor is a starting point of something is because it was the impetus for US involvement in WWII. However, we could just as easily start the narrative with attempts by European countries to involve the US in the war, with Hitler’s rise to power, etc. The way we frame starting points and turning points is just as important as the history overall — Eviatar Zerubavel’s work is focused on just this notion. If this subject interests you, I highly recommend it.

I also think Cohort has an important effect here, for sure. Applescruff, you say you were born in the late 80’s, which is earlier than many of my students and yet you were not taught about Kent State, which points to the importance of the education system in framing events as important or irrelevant for history. I wonder if your history book mentioned the event, since we never cover everything in our textbook in the classroom or if it was deemed irrelevant overall.