Can we play to address violence? Feeling vulnerable while free (at school) with LOVE

“Terroriste:

— Notebook entry of youth participant in LOVE program

This word resonated in my 5th grade ears during lunch. A girl who I had barely talked to began calling me this. It wasn’t just the 5 boys in my class would come up to me shouting ‘Allahu Akbar’ as if it were a joke.”

LOVE Quebec is a non-profit organization that offers programming to youth, through a social development approach with artistic means such as writing, photography, and drawing. Our research team (VOICE) has been studying the LOVE program for various years, to understand the social processes that make it effective. Our first study (Montreuil et al., 2018) had investigated LOVE’s Media Arts Program (MAP) in afterschool settings. For this second study (the topic of this blog), again through focused ethnography we explored the LOVE MAP, this time within two school settings. At the time of our study, LOVE was focused on violence prevention (for youth who have been exposed to violence as actors, recipients, or witnesses), but its mission later expanded to focus on mental well-being, emotional intelligence, and resilience. In the words of youth participants of our study:

“The LOVE program is the one time of the week where you can actually talk your feelings through, everything that you’ve been holding on for an entire week, and you can just let it go.”

“Like at school, like in class I mean, you’re focusing on one thing, you know like that one subject you’re in, and then in LOVE, you’re kinda, it’s like not a subject, it’s a time to focus on you.”

How does the LOVE MAP operate socially within a school context?

Yet how does LOVE do this? Before getting to play, it is important to mention that our study of LOVE in a school setting echoes certain themes from our first afterschool study about why and how it is effective, notably:

(1) Coordinators’ friendly/egalitarian approach, balanced by their gentle authority/structure and strengths-based support, different from teachers. As described by youth, coordinators are:

“just really great people, but also the fact that they can lay down the law, cuz there’s those moments where, like, ‘we’re all the same!’ But then there’s moments where they can take action…be like ‘we’re still in this you have to give it your attention’ and they’re able to still be responsible…it’s perfectly in the middle.”

“being themselves and also they can lead the group, without making other people feel like they’re, like, nothing. Like teacher-student the teacher is on top of all of you and like students are like the bottom. And [the coordinators are] like, ‘we’re on the same ground’.”

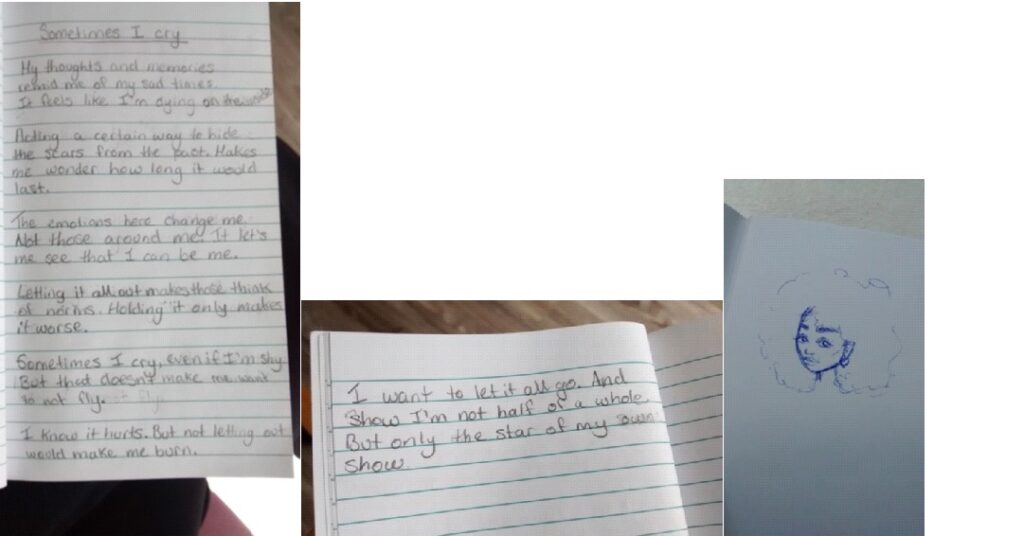

(2) A safe space fostering expression of vulnerability, encouraged by the above. For example, one activity encouraged youth to write with the theme “Sometimes I cry.” Here are some examples of what youth wrote:

“Sometimes I cry. 1:26am, I’m on my bed in tears not sure why an accumulation of things maybe. I’ve been broken by so many things yet had to hide it. We had a fight this one was different it was worse I can’t breathe. I’m on the chair about to burst being yelled at in my face I can’t breathe I can’t cry I can’t be weak and let him win. Reason 1 my family. I look in the mirror I can’t let it beat me poking at my face and body looking at the toilet bowl on my knees I didn’t do it. My mom came now I can’t cry. Reason 2 body last reason I can’t breathe I can’t think. Reason 3 depression I don’t know which is the culprit.”

Another activity fulfilled a similar purpose, by asking youth to write about a word that has hurt them (for example, the quote at the beginning of this blog). One youth wrote:

“Fat/thick boned

Fat is a word that hurts and even though people try to replace it with thick-boned or chubby I know what you mean…It’s a word I struggle with erasing from my self-image every day but I can’t. Fat is a 3 letter word that stabs you with every inch of it. It is a word that isn’t erasable with compliments. It is a word that gets fed with repetition.”

As a related example of how coordinators encouraged youth in their expression of vulnerability, one coordinator responded in pink writing in this youth’s notebook:

“Thank you so much for sharing this and allowing yourself to be vulnerable. You are strong [heart shape]. Looking forward to seeing & reading more of your writing. Much love –[LOVE coordinator’s name].

Furthermore, during the session after this youth had read the comment out loud, one coordinator read her own writing about being judged based on her weight, and another coordinator spoke of her difficult experience being negatively labeled “jew.” After reading their writings that day, some youth cried for the first time in front of the group. As one youth described it:

“Everyone (was) just talking and getting really emotional and just, being very vulnerable. That was one of the sessions that made me realize that we’re actually getting closer, I feel like that session made us one of the closest, because you see people telling their stories […] People actually getting emotional and even tearing up maybe, because they felt comfortable enough to say their stories.”

What’s play got to do with it?

If our study underlined the importance of the above factors, confirming findings from our article about the afterschool setting, it also highlighted something new: The significant role of play(fulness). In other words, playful activities and playful attitudes (for example, playing hangman on the black board or competitive team board games) increased the potential of the above factors. The above-mentioned activity and emotional opening (about hurtful words) was preceded with a playful game in which youth were asked to yell out all the hurtful words they knew for the coordinator to write them on the black board. It brought lots of laughter to the group,and one youth described it as “liberating” and “free.” Furthermore, the sessions leading up to that session had involved a diversity of playful games (e.g. icebreakers, fun questions, a photographic scavenger hunt, a trivia game about celebrities and their potential as role models).

As one youth noted: “I like the way how you kind of like play with it…like talk about problems in life, but play around with it with games, you know?” Echoing this appreciation of LOVE’s playful approach, when one youth was asked about a particular moment or experience that impacted them during the LOVE sessions, this youth answered:

“This is gonna sound really stupid, but the first time we played that game, with [LOVE coordinator’s name]. Cuz […] teachers rarely act like themselves in front of students. And in LOVE it’s not really like that, it’s not really a teacher-student dynamic, it’s more of like… people talking[…] so it was fun when we were able to jokingly be like ‘I’m gonna beat you’ [at the game…] and I felt really comfortable and happy […] It was the day I realized you guys aren’t teachers or coordinators, it made us realize you’re just people, and you’re our friends […] talking with us jokingly and like cracking jokes.”

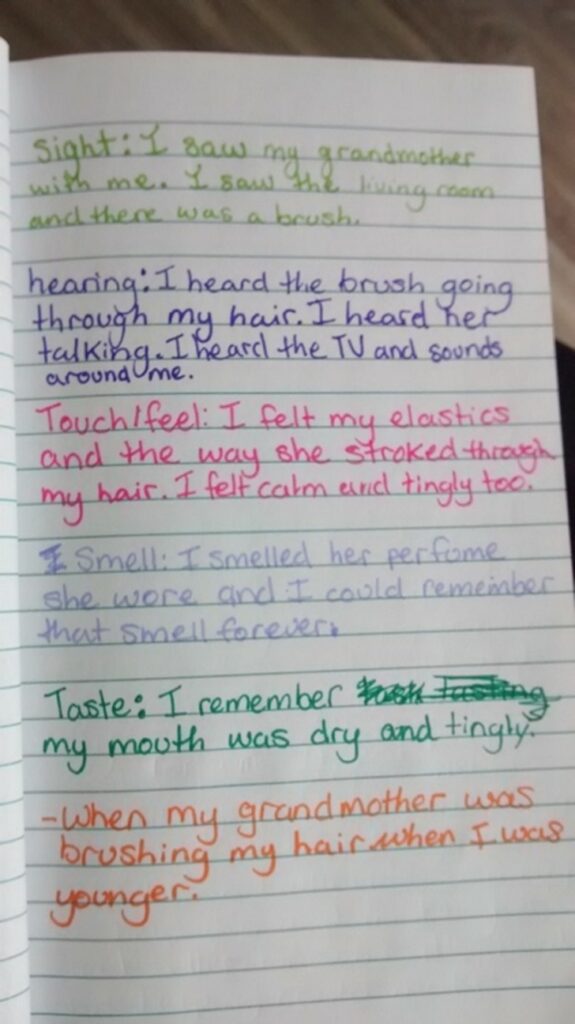

One activity, Five Senses “was initiated with a game during which youth volunteered to blindfold themselves to guess the nature of an object without seeing it, fostering laughter and intrigue, before writing,” our article explains. One youth said of this activity: “just thinking about the times I’ve had in the past and using those senses for that memory with my grandmother in my thing, it was emotional but it was really nice to write about.”

This was the youth’s notebook entry for that activity:

We concluded that play sparks a positive cycle: through the reduction of stress (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2018), encouraging youth to be themselves/spontaneous, and connecting youth to each other in creative/fun ways (Gordon, 2008), play “allowed them to feel free to open up to new possibilities and to transform their relationship to vulnerability -by expressing it.” In turn, their expression of vulnerability (in a safe, structured space fostered by strong relationships with coordinators) led to further feelings of freedom (from stress, to just be), connection/empathy, confidence/empowerment, and positive feelings about life and school.

What are the favourable and unfavourable impacts for youth?

Echoing previous research documenting beneficial impacts of LOVE on youth, this study’s findings found that youth were favourably impacted by the LOVE MAP in four ways, by allowing them to feel:

1. Free (from stress, to just be). For some youth, the benefit of LOVE included simply feeling “relaxed.” One youth spoke of “stress relief,” explaining that “right now I’m in a situation where, like, stress is involved, and writing…helped me… a lot.”This youth didn’t want to talk about it as she described her situation as “kind of scarring and.. kind of traumatizing” – but benefited by simply having a space to be distracted from their usual worries, “to help get things off my mind… and it’s, like, fun,” and to“feel kind of like myself.” Some youth specifically talked about feeling “free”:

“LOVE is your time to, you know, to be free…to say your opinion, you know, like without people to judge you. And to be open, you know?”

“Writing all my thoughts down on a paper and making a poem out of it that I can read later on, it just feels like… everything that’s in my head is free, like you feel free, all your thoughts are on a paper and you have nothing to worry about.”

2. Connected and empathic. As one youth said, “you just don’t feel alone anymore.” One youth explained: “When you talk about it in LOVE, and you find out oh my god this person went exactly what I went through, it’s so relatable, like we bonded over that.” Another youth said: “With the LOVE program I find I can talk to more people, open up a little bit, like instead of keeping everything to myself.” Another youth explained:

3. Confident and empowered. One youth described:

“I was really scared to be so open. Especially about my mental health. But overcoming it made me feel empowered[…] knowing I was strong enough to overcome my fear [thanks to…] the thought of knowing that there were others in my situation. That me speaking about it could help them come out as well […] everyone just started snapping their fingers all of a sudden [in support…] I just felt really proud of myself [..] I felt very vulnerable and I felt very powerful.”

4. Positive feelings about school and life. As one youth explained it: “At LOVE I feel like (raises her voice) ‘Wooo!’ I feel like I’m fly, you know? […] I feel good about myself.” Another youth explained:

“I’ve never considered school and friends [like] family […] But being part of LOVE and having that once a week is like ‘OK I’m going to see my family… like we walk in there full of joy.”

Conclusion

In part through play, LOVE helped these youth to feel safer, less alone, less stressed, more confident and empathic, and free to be themselves at school (and beyond). In such a way, they learned social-emotional skills, in a way that didn’t avoid conflict nor difficult emotions -something for which SEL programs have been criticized (Stearns, 2019)- with playful non-teachers, affecting their experience of school and of life.Our findings thus contribute to existing research by suggesting that playfulness is a key ingredient for social development programs for youth -and, we might add, a key ingredient to feeling and being alive (Graeber, 2014).

You can read about this in more detail in the academic article published in Children & Society here. All references cited here can be found in the article.

Hausfather, N., Montreuil, M., Ménard, J.-F., & Carnevale, F. A. (2023). “Time to be free”: Playful agency in LOVE’s in-school programme for at-risk youth. Children & Society, 00, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12803

This research was conducted by the VOICE Childhood Ethics research team (VOICE: Views On Interdisciplinary Childhood Ethics) project, https://www.mcgill.ca/voice/.