Of bodies and burkinis: institutional Islamophobia, Islamic dress and the colonial condition

by Dr Kimberley Brayson, University of Sussex, UK · Published · Updated

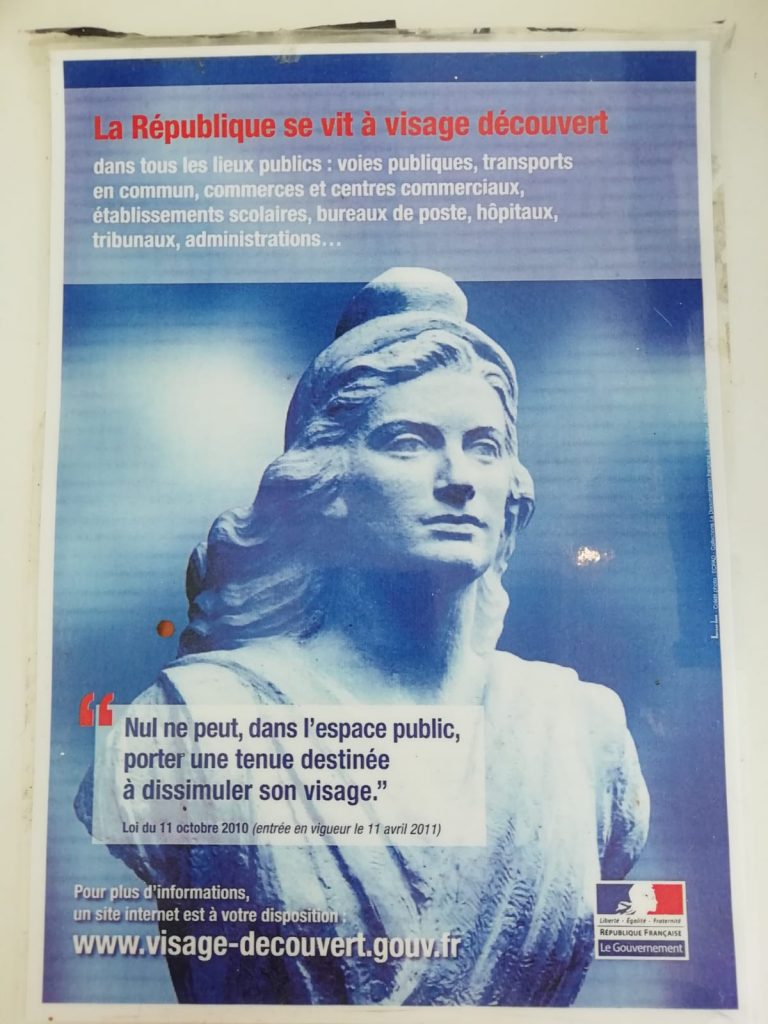

The image accompanying this piece was taken last month in France. The image is of a poster that was displayed on the wall of a beach front café, set against the backdrop of armed troops parading the beach front. The overwhelming impression of the poster is the bust of Marianne, her flowing locks said to represent the freedom of the French Republic. She dominates the image, exemplary of what it means to be a woman in France.

The poster is in fact a public display of French law 2010-1192, which makes it a criminal offence to cover the face in French public space. Contravention of this law is punishable by fine. The law is ostensibly presented as restricting equally the freedom of anyone in a secular French public space.

Through case law of the French Conseil d’Etat,[1] the highest administrative court in France, it has been established that French law 2010-1192 is in fact aimed at Muslim women wearing Islamic dress that covers the face and, unlike the image of Marianne, the hair. This law has been challenged at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in the case of SAS v France [2] but was ultimately found by the court to stand up to human rights scrutiny. This decision by the ECtHR was justified on the basis that the law was necessary in a democratic society in order to enable ‘living together’.

Since the inception of the law there has been an increase in incidents of what has been diagnosed in the UK as hate crime against Muslim women and notable instances of ‘burka rage’ where members of the public have felt empowered to tear Islamic dress from Muslim women in French public space. This speaks to the sociological significance of law in shaping and validating attitudes and actions in relation to Islamic dress and Islamophobic behaviours.

The institutional Islamophobia embodied by French law 2010-1192 is echoed or pre-grounded in statements from political figures in France such as former Prime Minister Manuel Valls who stated that the naked breasts of Marianne better represent the French Republic than headscarves. Marine le Pen of the French National Front has described a reverse colonization of France by Muslim communities and has proposed banning Islamic dress as a method to eradicate terrorism in France, a conflation and descriptive sleight of hand that disproportionately targets Muslim women as the avatar of terrorism and gender oppression. André Gerin of the Communist opposition compared the veil to ‘a walking coffin, a muzzle’.

This ongoing controversy over Islamic dress in France has recently flared up again. Catalyzed by the recent heatwave in France, the debate over the burkini in French public space has been reignited. The initial controversy over the burkini surfaced three years ago in 2016, when in the wake of French law 2010-1192 a number of municipal authorities issued local edicts banning burkinis on beaches; the burkini can be likened to a wetsuit with a hood.

On 24 August 2016 a Muslim woman lying on the beach was approached by four armed policemen and asked to remove items of clothing that were considered to contravene a rule enacted in the wake of the Bastille Day attack in Nice, which had been claimed by Islamic State. She was also issued with an on-the-spot fine. The rule referred to ‘correct dress, respectful of accepted customs and secularism, as well as rules of hygiene and of safety in public bathing areas’.[3] The image of this women surrounded by four armed police men resonated around the world and presented a reality that shocked many and inspired acts of solidarity such as an impromptu beach at the French Embassy in London. Solidarity notwithstanding, the Nice incident was particularly noteworthy as a potent reminder of the precarity of colonial bodies in public space.

The action of this woman being required to remove clothing by armed policemen demonstrated in a startling manner the diffuse power of the French state at its most violent in suppressing and subsuming colonial narratives through eliminating colonial subjects from public space. The erasure of the colonial markers of this woman was performed on the beach in Nice for all to see and institutionalized by catachrestic legal definitions,[4] most notably the criminalization of visibly Muslim women through the enactment of French law 2010-1192. The reality that such an incident could take place in a public space in 2016, be justified on the basis of gender oppression, national security and a human rights narrative of ‘living together’ endorsed by the ECtHR, needed to be critically unpacked. The instrumental use of both French domestic law and the human rights of the ECtHR to pursue neocolonial, Islamophobic policies in France required deeper analysis. Although only directly relevant to a small proportion of the population of in France who wear full face covering Islamic dress, Islamic dress has become politically potent, fetishized and distorted in French public political discourse. In this context, the French version of secularism, laïcité, acts to justify all manner of political agendas. As Altglas has analysed, ‘laïcité is what laïcité does’.[5]

Muslim women and Islamic dress

The term `Muslim women’ is inherently problematic for the universalism that the term propagates, denying cultural variations and specificities. For the purposes of this research, the term should not be understood as essentializing Muslim women as a homogeneous group. The term Muslim women is therefore employed in a strategic manner,[6] and is understood in its situated and materialist context as disclosing many divergent realities. The controversies surrounding Islamic dress depend on the situated context in which they take place. Context notwithstanding, the persistence and unresolved nature of these controversies unifies varying discourses on Islamic dress.

Islamic dress is understood variously as constituted through difference to include the hijab, a veil or headscarf; jilbab, full black dress head to toe; burqa, a cloak covering the whole body including the face; niqab, the face veil. The burkini can now be added to this list. The oft-witnessed conflation of these forms of Islamic dress in legal judgments and legislation points to the fact that these acts of censure are strategic and instrumental in pursuing wider political aims. In the context of French restrictions on Islamic dress, the strategic political aim is the assimilation of colonial bodies in pursuit of neolcolonial aspirations.

Critically contextualising Islamic Dress

The arguments presented here form part of an ongoing project of a critical contextualisation of the legal treatment of Islamic dress in an attempt to push beyond the repetitive representational logics of gender and national security. This is not to call into question these analyses but rather to demonstrate how these logics and a discourse of feminism have been appropriated for the political ends of (neo)colonialism and to broaden the kaleidoscope of theoretical lenses through which to analyse Islamic dress.

I argue that shifting legal justifications of gender oppression and national security simultaneously obfuscate and enact a strategy of colonial assimilation that controls Islamic bodies in public space. As decolonial scholars explain, colonial matters are not resigned to history but structure the temporality of the past, present and future. Colonialism is therefore the condition of modernity, which in its socio-epistemic form permeates knowledge production and modes of being in the world.[7] Colonialism is therefore the epistemic lens through which knowledge on Islamic dress is produced and resurfaces as Islamophobia in contemporary discourse. I interrogate how the logic of gender oppression and the logic of security are used instrumentally to divert attention away from and eclipse the colonial substratum that is fundamental to, yet absent from, Islamic dress in French legal and public-political discourse.

The analysis demonstrates that the colonial and racial dimensions are constitutive of the complexity of the Islamic dress debate but are purposely obscured from public consciousness. A distinctive critique of the current legal approach to Islamic dress is developed, which draws on a broad range of postcolonial, feminist, and phenomenological literatures as well as analyzing and challenging relevant ECtHR and French legal judgments. By drawing out the colonial dimension the research analyses a rarely-told aspect of French society and critically engages with the French nation and the French Republic, secularism and assimilation. Recourse to phenomenological literatures facilitates the conceptualisation of the whiteness of French public space and institutions. [8] The research shows how Institutional Islamophobia in the French context acts like racism[9] to stop Muslim women in their tracks and exposes the instrumental role of law and human rights in creating space for this agenda.

The conclusion is that Islamic dress cannot and should not be thought apart from the colonial lens. You can find the full article free to access until end of 2019, here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jols.12142

[1] Conseil d’Etat, decision du 7 October 2010 no 2010613.

[2] S.A.S v France (2015) 60 E.H.R.R. 11.

[3] Conseil d’Etat, decision du 26 Septembre 2016 no 403578.

[4] J. Butler, Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative (1997) 72.

[5] V. Altglas, ‘Laicité is what laicité does: Rethinking the French Cult Controversy’, (2010) 58:3 Current Sociology, 489.

[6] G. C. Spivak, The Post-colonial Critic: Interviews, Strategies, Dialogues, (1990) 11.

[7] S. Posocco, ‘(De)Colonizing the Ear of the Other: Subjectivity, Ethics and Politics in Question’ in Decolonizing Sexualities: Transnational Perspectives Critical Interventions eds. S Bakshi, S. Jivraj, S. Posocco (2016) 250.

[8] S. Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (2006); F. Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks (1986).

[9] R. Itaoui, ‘The Geography of Islamophobia in Sydney: mapping the spatial imaginaries of young Muslims’ (2016) 47:3 Australian Geographer, 261, 262.

Dr Kimberley Brayson is a Senior Lecturer at theUniversity of Sussex, Department of Law, School of Law, Politics and Sociology, Freeman Building, Brighton BN1 9QE, England

1754-9469/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=9197a1a6ba8c381665ecbf311eae8aca348fe8aa)