Buying Time: Stefano Sgambati’s Sociology of Money, Debt & Finance

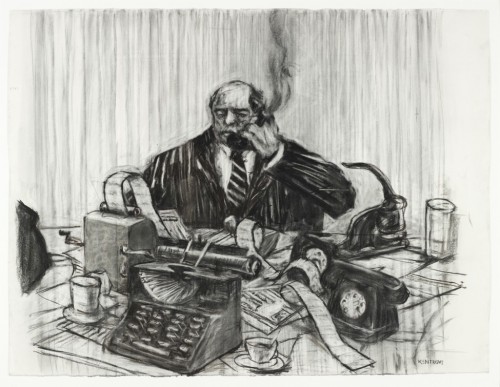

Photo by Nathan Keay, (c) MCA Chicago: William Kentridge (1995-96), ‘Drawing for the film History of the Main Complaint’

Writing for the Guardian’s Comment is Free blog yesterday, David Graeber warned that we may be heading towards yet another crisis of the kind we saw in 2007–08. In his Comment, Graeber takes to task George Osborne’s 2015 Mansion House speech (or rather the logic underpinning it), in which Osborne made a commitment to run a budget surplus in ‘normal times’, much to the consternation of dozens of academic economists. It seems that the utterly misleading and moralizing analogies so frequently made between well–disciplined householders ‘tightening their belts’ when times are tough, and the national government cutting its spending to pay down its debts – part of the mythos termed ‘mediamacro’ by Oxford macroeconomist Simon Wren-Lewis – simply won’t go away. And yet, as Graeber shows, “the less the government is in debt, the more everyone else is…If the government reduces its debt, everyone else has to go into debt in exactly that proportion in order to balance their own budgets.” Everyone cannot simultaneously ‘balance their budgets’ and continue to interact, because all money is debt, as the Bank of England ‘revealed’ in January 2014: “Rather than banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them out, bank lending creates deposits.”

Similarly, at last week’s launch of his new book Between Debt and the Devil, Lord Adair Turner, who took over the Financial Services Authority as the 2007–08 crisis began to unfold, suggested that the UK has reached a position in which our debts are not being paid down, but simply shuffled back–and–forth between the public and private sectors – though the vast majority of ‘private sector’ lending is going into a game of property speculation played by the wealthiest, at the expense of the most vulnerable. For those seeking to make sociological sense of this scenario, the recent work of Stefano Sgambati, at the University of Naples Federico II, provides one of the most powerful pathways to making political and theoretical sense of money, debt and finance in the modern economy.

In a contribution to European Journal of Sociology published earlier this year, Sgambati critically engaged with Geoffrey Ingham’s influential sociology of money. Ingham’s work can be read as a corrective to the orthodox economic account of money as primarily a ‘medium of exchange’. According to this view, money, as a medium of exchange, emerged out of barter, as a way to make barter ‘scale’ between parties who cannot trust each other or do not have an immediate ‘coincidence of wants’. (See David Graeber’s entertainingly uncompromising rebuttal of this rather ridiculous narrative here.) In contrast, Ingham emphasizes the ‘unit of account’ function of money, and the role that states or other large bureaucracies have played in underpinning the social claims made possible by money as a unit of account. Michael Hudson makes a similar argument to Ingham, suggesting that even silver money emerged not as a kind of ‘commodity’ money, but as a unit of account that was accepted for the settlement of debts by large religious and royal bureaucracies in Mesopotamia. Sgambati, however, argues that “the most specific attribute of money ‘as we know it’” is neither the medium of exchange function nor the unit of account function (and only partially found in the store of value function). Instead, the most specific attribute of money is “purchasing power” (p. 309) – or, more accurately, the power not to pay. Those with money are in a position not only to make claims on society, but to withhold payment from those who expect it.

Sgamabti criticises Ingham for invoking an ‘extra–economic agency’ (i.e., the state) as an explanation for the various historical developments leading up to modern money. In particular, Sgambati has in his sights Ingham’s invocation of sovereign power (the taxing authority) as part of his explanation for why it is we experiencing a promise of payment (debt money) as a means of payment. (i.e., Ingham focuses on the state’s ability to establish a unit of account through taxation, and the state’s capacity to use coercive power to determine what can be purchased with that money.) Thus “orthodox theory is unable to explain why and how money gets historically constructed so as to bear purchasing power” (p. 316). The answer, suggests Sgambati in his European Journal of Sociology paper, and in a forthcoming piece for New Political Economy, is to attend to the liquidity or exchangeability of debt:

“the significance of money in such an infrastructure of liquid debt relations is precisely that it bears the potential not to pay, that is, to be withdrawn from exchange sensu strictu and be instead channelled into the speculative buying and selling of debts, to the point of bringing overall exchanges to a stall, as in financial crises, and with the consequence of turning pro tem suspensions of debt settlements into a structural impossibility to pay the debt” (EJS, p. 327)

If we understand money as purchasing power that is issued as exchangeable debt, and which can be withdrawn from exchange in order to pursue the further creation of money, then the situation that Lord Turner described at his book launch – of around 60–70% of bank lending going into a vicious game of Monopoly played by those capable of participating in the collective effort that is the housing bubble – is revealed as an inevitability of our current banking–monetary system.

In Sgambati’s New Political Economy paper, the techniques that make this system possible are delved into further. Where his EJS paper started by dispensing with the barter myth of monetary origins, the NPE article begins by dispensing with the fractional reserve model of banks as intermediaries – that which the Bank of England dismissed last January (see above), but the consequences of which few seem willing to faceo. Playing on the shared etymology in many languages of words for ‘debt’ and words for ‘sin’ or ‘guilt’, Sgambati asks,

“why is it that banks, namely those who allegedly get to lend money in virtue of their exceptional credit, are in fact the biggest debtors on earth – so indebted that following the global financial crisis they have been basically granted with the privilege of not paying for their ‘sins’?” (NPE, p. 2)

Rather than mere intermediaries who ‘take the risk’ of lending out depositors’ money to various customers at a slightly higher interest rate than that at which they themselves borrow, banks produce the exchangeability of debt that allows modern finance to occur. In fact, banking is “the art of swapping other people’s debts, which are less credible and secure with banks’ own debts, which are much safer and more credible” (NPE, p. 8). This establishes a regime of mutual and permanent indebtedness that sees – as both Graeber and Turner have pointed out – alleged efforts to ‘pay down’ debts effectively shuffling indebtedness back and forth between the public and private sector. When banks ‘purchase’ assets and ‘issue’ loans, they are effectively buying other people’s debts (usually owed to other banks), at a discount, and exchanging them for the bank’s private (largely electronic) IOUs: “in exchange for the debtor’s promise of payment, the bank makes its own promise of payment which, unlike the borrower’s own, is readily negotiable and generally accepted at par” (NPE, p. 12).

In other words, by making debt liquid, transferrable and exchangeable, purchasing power is able to both circulate and be withheld or channelled into speculative games for the already–wealthy. These games are not oriented towards ‘cashing out’ once enough has been made, but on buying time and deferring debt settlements (while you enjoy the purchasing power that successful participation in games of property speculation or mortgage-securitization grant you). To focus on ‘settling’ debts (as Osborne partially wants us to) is to misdiagnose the point of this game. And in his NPE piece, Sgambati hints at more forthcoming work that examines how we maintain the faith that there is something beyond this liquidity.

With Sgambati’s work, it is possible to make theoretical and political sense of how modern money creation, ill–advised macroeconomic decisions, and speculative bubbles or financial crises are intimately connected: through the creation of money (purchasing power) in the form of liquid (exchangeable) debt by (permanently and mutually indebted) private banks. Perhaps his work could also help to inform a radical politics that, as Sahil Dutta argues, must increasingly be based on disrupting, confronting and appropriating debt relations, rather than on the politics of organized labour.

Further Reading:

Sgambati, S. 2015a. The Significance of Money Beyond Ingham’s Sociology of Money. European Journal of Sociology, 56(2), pp. 307–339.

Sgambati, S. 2015b. Rethinking Banking: Debt Discounting and the Making of Modern Money as Liquidity. New Political Economy, forthcoming.