The Madness is in Our Nature

Recently I returned to Quito after a short trip to the UK, where I attended the aptly named CAOS (the Centre for the Anthropology of Sustainability) conference at UCL. I also got some much needed guidance from my supervisors (Dr Evan Killick and Professor James Fairhead), and spent some wonderful time with friends and family, who I have dearly missed while I have been away on my fieldwork. While I was there, a close friend told me he had been reading my blog and that he loved the first three I had posted because they were thoughtful, open and honest, but the rest seemed to just be ‘basic journalism’. I think he is right. After the first few (for a number of reasons) I just didn’t have the time or energy to put too much of myself into what I was writing. I am going to try rectify that a little here by reflecting on something that Professor Bruno Latour talked about at CAOS (where he was the keynote speaker); something that really struck a chord with me… “The Four Ways to be Made Mad by Ecological Mutations.”

I think everyone I know (myself included) is a little bit mad in some way or another. It’s an odd word, though, ‘mad’; and it can be somewhat contradictory. On the one hand it can mean irrational or deluded (see my earlier post for my thoughts on being rational) while on the other it can mean wildly excited, angry or enraged, which, paradoxically, can be a quite rational response to certain circumstances. Sanity may indeed just be “a madness put to good uses” (Santayana, 2009, p. 269), and the question might be not whether we are mad, but what type of madness we feel and, more importantly, how we use it.

At CAOS, Latour addressed a scholarly bunch of a few hundred people, most of whom have probably been studying or researching issues relating to the environment for some years. I was sat right at the back of the room and, though I had been looking forward to hearing him speak, I was tired from all the travelling and I was fully prepared for the majority of Latour’s talk to go way over my head (his writing sometimes does). But the first question he posed “has nature become mad?” was something I had been asking myself for some time. The answer, I think, is yes (I will write another post explaining why I think this is the case), and here are my thoughts on Latour’s suggestions of some of the ways that anyone who thinks about it enough might end up a bit mad, too.

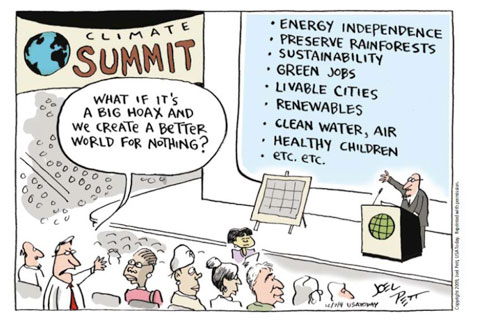

1. Denial or Quietism

This, for me, might well be the most dangerous type of madness. Though I went through phases of them both myself, I believe we have now reached a point where enough knowledge exists to say with some confidence that yes, the climate is changing and that it is, to a large extent, the result of human actions. This isn’t really controversial anymore; various meta-analyses of scientific papers find that up to 97% of scientists support the Anthropogenic Global Warming hypothesis (AGW). Moreover, this is one of the few areas where, academics, activists, governments, Indigenous Peoples and even huge transnational corporations seem to agree.

There are, of course, some scientists who claim that climate change is happening as part of a “natural” process (whether natural is non-human or not is a whole other discussion), and that there is an ongoing climate science conspiracy that claims the evidence of human influence has been invented or distorted for someone’s financial gain. But there is little evidence of this. In fact, there is significantly more evidence of the opposite. For example, it has recently been revealed that Dr. Wei-Hock Soon of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who has been a key figure in denying AGW by arguing that climate change has been caused by changes in solar behaviour, received more than $1.2 million from fossil fuel corporations and conservative groups. Dr. Soon, one of the most cited AGW deniers, failed to disclose ties to funders including ExxonMobil, the American Petroleum Institute, and the Charles G. Koch Foundation.

Despite overwhelming one-sided evidence, many people I have met give equal weight to the small number of climato-skeptics as they do to the majority of scientists who acknowledge AGW (I don’t usually like to cite Wikipedia, but the summary of the scientific opinion on climate change is a good starting point for anyone who is interested). They often pick up on individual mistakes or misleading comments and claim that they prove climate change isn’t caused by humans (such as this article in Forbes about the “97% of scientists” claim) or say things such as: ‘well, we can’t really be sure that it is caused by humans’ or ‘the climate is always changing… isn’t it arrogant to think that we caused it this time?’

Though the labyrinth of information can make it hard to decide what is worth believing and what isn’t, I think that climato-skepticism or outright denial is a type of madness based in fear of our own mortality. It is easy and safe to believe that either a) we didn’t cause it and there is nothing we can do about it or b) a group of people somewhere is making it all up for financial reasons. What is far more difficult is to accept is that it isn’t some elaborate conspiracy and that the world is just not that organized; it is far more chaotic. Something catastrophic is happening and we are all (to varying degrees) responsible.

2. Megalomania

The worst thing about this second type of madness is that it seems to be based in optimism and a desire to live in a better world. People who have managed to overcome or bypass denial or quietism bravely accept that we humans are having an impact on the world through our use of resources and technology. Sadly, though, these people seek the solution in the same place as the problem is to be found. This approach brings to mind the Albert Einstein quote I put on the first page of my MA dissertation about REDD+: “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them”.

Doubtless, there is a place for technology in the struggle against climate change, but it alone will not be enough to stop or even begin to mitigate the damage that is being caused. This is noticeably the case, because much of the technology that could potentially have a positive impact already exists, but it is not implemented. We must ask, then, why not? A significant factor is the economy, particularly two features of the market. As Jaffe, Newell and Stavins (2014, p.1) note, research into and availability of such technologies are limited because: “Market failures associated with environmental pollution interact with market failures associated with the innovation and diffusion of new technologies”. The limitations of the free-market economy mean that it does not (and cannot) account for pollution and other environmental ‘externalities’. Thus, technologies that take these costs into account will generally be at a competitive disadvantage. Moreover, many industries that rely on pollution as a byproduct, particularly the fossil fuel industry, receive significant government subsidies, estimated at between $775 billion and $1 trillion annually. Of course, this just adds to the competitive disadvantage of being ‘green’.

The other side of the relationship between technology and the environment, the far more megalomaniacal side, is the burgeoning climate/geo-engineering industry that seeks to reengineer the global environment and reverse the effects of climate change. The ways in which this is hoped to be achieved are quite incredible, in multiple senses of the word. In one way they are remarkable and spectacular; testament to the ingenuity and creativity of humanity. Yet, they are also a quite far-fetched and, at times, they are utterly incredulous, demonstrative of humankind’s inability to accept the limits of its own power.

Of the many proposed methods through which science could actively halt or reverse climate change, most fall into two categories: Solar Radiation Management (SRM) and Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR). But numerous projects are being developed, ranging from relatively mainstream ideas such as reforestation and reduction of deforestation (e.g. REDD+) to weird and wonderful concepts such as extraterrestrial sunshades (essentially a planet sized parasol in space) and cloud seeding (which causes clouds to release precipitation by ‘seeding’ them with particulate chemicals such as silver iodide).

Though some see geo-engineering as an inevitable part of the anthropocene – (in itself a highly contested concept – see e.g. Oldfield et al, 2014), it raises some important questions. What will we do to mitigate the problems that might be caused by geo-engineering? It has, after all, taken this long for the world at large to accept that climate change is happening and that something needs to be done. How long will it take to understand the unintended effects of intentionally changing weather cycles or partially blocking out the sun? And what if it just doesn’t work? There are good reasons to continue to study geo-engineering, but relying on technology and the economy to fix problems that were caused, at least in part, by the free-market and the unchecked development and use of resources is fraught with risks that are poorly understood and are almost impossible to regulate at the international level. Moreover, as they do nothing to change the underlying behaviours that have caused the environmental degradation in the first place, SRM and CDM (if they work at all) can at best be seen only as a temporary solution to a permanent problem (see e.g. Hanafi, 2014 & Smith, 2014); to see it as anything more is madness.

3. Depression and Despair

In light of the abundance of the first two types of madness, depression and despair can be difficult to avoid. Add to this the sensationalist and pessimistic media coverage of environmental issues, and hope can seem naïve. The dominant discourse catastrophises the future and harbingers doom (Stephen Emmott’s ’10 Billion’ being one particularly ‘misanthropic’ example). Almost daily we hear of new ‘natural’ disasters, stories of industrial pollution (‘accidents’ or otherwise) that will only be surpassed by the next, and the continued decimation of plant and animal species. But rather than inspiring change, it only makes denial and quietism all the more attractive.

For me, the academic world can be just as discouraging. Most of the articles I read nowadays are critiques of projects that try to combat climate change but are getting it very, very wrong. For example, REDD, the project that I study (one of the biggest environmental initiatives in the world), seeks to mitigate climate change by reducing carbon emissions that are being caused by deforestation and forest degradation. But it relies heavily on the power of the market, specifically the burgeoning carbon market, which aims to ‘offset’ the carbon emissions of polluters, to drive it forward. Though billions of dollars are being spent on building an infrastructure for REDD+, it is full of holes and has been heavily criticised. Many critics (myself included) do not believe that it will reduce the amount of carbon in the atmosphere at all.

I currently live in Ecuador, a country that is often cited as one of the most environmentally progressive nations in the world, and is listed as one of the UN’s REDD Early Mover (REMs), yet it is also one of the economies that are most dependent on hydrocarbon extraction, a precarious position at this time. For every environmental project that starts, it seems a new oil well is drilled or a new mine is opened. What is most depressing about this is that I have never known a country where thinking about and discussing the environment is such a major part of the national discourse. Everyone seems to talk about it, there are environmental magazines (such as Terra Incognita), it is written about in newspapers everyday, and there is a strong network of students and young people, NGOs and Indigenous peoples who campaign every day to protect the country’s forests, mangroves and other ecosystems. Despite this, Ecuador continues to expand its oil extraction activities (up to 90% of which is used to repay the country’s debts to China) into the mega-diverse Amazon national parks and into Indigenous peoples’ territories, bringing with it continued deforestation and contamination.

With these things in mind, I often wonder what the point is at all. Why bother studying these issues if the political will does not seem to be there and the economic imperative of growth and development is apparently impossible to overcome? The worry is that my research is pointless and really won’t make any difference at all. Going to CAOS, where a main point of discussion was where we (as anthropologists) can position ourselves in the debate about sustainability, helped to remind me that anthropology “has a unique contribution to make towards research in sustainability and towards integrating multidisciplinary studies on ways of living that do not damage the ecological systems of which we are part”.

Nonetheless, it is difficult to see the value of my own research on a day-to-day basis. Sometimes it feels like everyone already knows enough to know what is going wrong, yet little is done to change the way things are. When I discussed this with my supervisors, they both said similar things. The only way to avoid going completely mad when studying this type of thing is to endeavour to separate personal anxieties and/or despair from your research, and to not expect, or even hope for, your work to make that much of a difference (leave that to the megalomaniacs). I am trying to do this, and have succeeded to some extent. I have begun to view my work as a part of a bigger process in which we are collectively learning how to think about the world, and how we interact with it and each other, in different ways. I have not yet, however, managed to consistently maintain a significant degree of the fourth type of madness…

4. Enthusiasm

Like madness, enthusiasm is a complicated word. It is usually associated with positive motivation, but all it really means is that you have an intense feeling or interest in something. It can just as easily be fuelled by anger. Latour stated in his keynote speech that environmental activists and naturalists (and maybe saints) are probably the only people who can confront climate change with such zeal for any significant period of time.

I think that activists are often able to see the world as a binary system of us and them; ‘they’ are the governments, the multinational corporations and the economic elite, while ‘we’ are the 99%. It is relatively easy to be enthusiastic when you know who your enemy is. Sometimes this distinction is quite justified and effective. The Indigenous peoples, for example who are tirelessly defending their forest territories against the incursions of oil, mining and other industrial expansions, quite rightly draw distinctions between their traditional lives and the values of external cultures. Sitting here writing this on my Macbook, though, I don’t feel as though I can draw the same lines. Naturalists are quite lucky, in that they get to think about the beauty, wonder and complexity of the natural world without (necessarily) having to think about it in its cultural, political and economic context. Anthropologists (and academics in many other disciplines) do not have this luxury; ‘Nature’ is no longer seen as separate to human and cannot be studied as such.

This leaves me in a difficult situation. As I have progressed through my academic career, I have (like many people) realised how little I know and how little I understand. The world has gradually appeared more and more complex, and what seemed so simple before now seems almost incomprehensible. Where I was once an activist, I no longer know who to be angry at, and where I once marveled at the beauty of nature, I now rarely consider it without thinking of the dreadful loss that the world has endured and will continue to endure if nothing changes. In a situation so convoluted I would be mad to be enthusiastic, and to say I am optimistic would be a lie. But I do have hope.

Hope: A Madness Put to Good Uses?

In a world where being mad appears to be the norm, it is difficult to have hope without feeling as though it might also be a form of madness. But if it is, it is a madness that can be put to good uses. Hope has long been understood as a way of coping with the world and, as Korner (1970, p. 134) noted, a loss of hope can have dangerous physical and psychological consequences. Its key purpose is avoiding depression and despair and by allowing one to envisage a future that can be better, hope can also subdue fear, the driving force behind denial and quietism. But more than just a defence mechanism, or a reaction to circumstances, it also has the potential to be a methodological approach to anthropology.

Miyakazi (2006, p. 164) states that “theorists such as Harvey and others […] restore hope to the work of critique [and] entail a reorientation of a sort: Their explicit attention to hope as a method of critique, together with their search for alternatives to capitalism, make a significant departure from the search for ironic openings in the midst of globalisation and neoliberalism.” Approaching research from this perspective allows one to go beyond the narrow limits of the extant social, cultural and economic norms, instead creating spaces in which we can imagine alternative ways of being and knowing.

Hope, then, is not the same as optimism: it is not so naïve. Nor is it, like enthusiasm, the result of an intense emotion, but instead has the potential to free us from fear and rage. It is an empowering and liberating way in which to view the world and a tool through which we have the potential to move beyond destructive exploitative relationships and interactions, both among ourselves and with the world on which our lives depend. I am relatively new to this idea of hope, and these are really my first thoughts on the subject, but the more I consider it, the more I think it might just be the type of madness that I need.

1754-9469/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=9197a1a6ba8c381665ecbf311eae8aca348fe8aa)

1 Response

[…] The Madness is in Our Nature […]