Researching Young People and the Social Construction of Youth

Next time you read research about young people ask why is it focussing specifically on their age. It is still taken for granted that the process of maturing from a child to adolescent to adult unfolds as a series of naturally occurring stages, that there is a right age at which children should develop certain competencies and acquire certain freedoms and responsibilities (Scott, 1999).

Contemporary sociological research, however, has “highlighted the blurring of boundaries between youth and adulthood and the destandardisation of the life course” (Reisinger, 2012, p96). Griffin (1993), Lesko (2012), and Seaton (2012)) argue youth’s development is complex, non-linear, sophisticated, and dynamic; it involves a mutually defining interaction between asynchronous biological changes and multidirectional environmental and social influences. Any research that fails to acknowledge this, by default, treats youth and age as a self-evident, timeless and unproblematic category.

To demonstrate this I will briefly unpack the history of youth as a social category. As we have transformed from an agricultural to post-industrial society our definition of youth has evolved. Young people used to be parental property; nurtured by domestic folk practices then forced into work and afforded no legal rights. Youth today is a public institution; objectified by the state, preserved in law, commodified by business and studied and monitored by rational, scientific expertise. Youth, as I will explain, have been transformed from disempowered mini-adults to today’s instruments for influencing the future in a way that “reduces and homogenises” youth (Lesko & Talburt, 2012, p14).

Pre industrial European societies had no clear categories for pre-adult phases of life. The notion of childhood or adolescence as a distinct stage of life or a social category that afforded political and social rights is a recent invention (Zelizer, 1994). The aristocracy aside, previous generations and their social institutions have regarded children primarily as a source of cheap labour (Cunningham, 2009). In 1821, approximately half of the workforce was under 20 (The National Archives, 2012). During the nineteenth century, the increased concentration and visibility of child labour in towns and cities and a growing middle class, some of whom were preoccupied by social reform, helped construct models of childhood and society‘s obligations to them. After 1867, no factory or workshop could legally employ any child under the age of 8 and employees aged between 8 and 13 were to receive at least 10 hours of education per week (The National Archives, 2012).

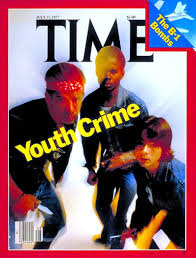

Two trends emerged during this time; the sentimentalisation of childhood and the construction of a new category to describe the transition from childhood to adulthood: adolescence. Younger people began a transformation from a domestic economic resource to objects which embodied public institution of pure childhood to be protected and nurtured. Adolescents, beyond school, were given to apprenticeships to learn the roles and responsibilities of adulthood. Ideal types were created and used to protect and civilise urban working class groups (Griffin, 1993). For the wealthy, public schools became engines of moral improvement that turned out ideal leaders equipped for the duties of empire (Griffin, 1993). How youth developed, learnt, behaved; what they represented and believed became an issue of state and public concern. As a result, youth departed from being intrinsic to the state of being young (Scott, 1999) to become a problematised moral classification (Qvortrup, 1994).

In this context a laissez faire approach to youth, abandoning them to fate, was seen as a recipe for “moral anarchy” (Lesko, 2012, p75). In the late 1800s the line between youth and adulthood became sharper more intently watched (Lesko, 2012, p74). Lesko and Talburt refer to the emergence of “pastoral power” during this period: an era of characterised by a “distributed discipline among adult authorities and youthful subjects who internalised regulations to monitor the self” (Lesko & Talburt, 2012,p13). By the early twentieth century, youth was “under the administrative gaze of teachers, parents, psychologists, play reformers, scout leaders, juvenile justice workers” (Lesko, 2012, p75). The persistent imagined threat of moral anarchy combined with the affordances of pastoral power meant anyone with the power to exercise this administrative gaze could easily justify an intervention; problematise youth and influence its social shaping. In modern societies this increasingly became the domain of experts.

American psychologist G Stanley Hall, for example, is usually credited with the discovery of adolescence (Griffin, 1993). He used his privileged position as an expert to synthesise a range of discourses influenced by nineteenth-century western ideologies around race, sexuality, gender, class, nation and age (Griffin, 1993). Hall argued that, as they develop, individual children recapitulate the same evolutionary steps as do human groups as they reach toward higher civilised stages (Lesko & Talburt, 2012, p12). In short, the journey from childhood to adulthood, with all its religious and supremacist connotations, was ascension of the Chain of Being (Lovejoy, 1936) from primitive state governed by drives and impulses to civilised, rational state of self-government and control.

While for obvious moral and legal practicalities we need age boundaries, in research, operationalising age can neglect important, socially-shaped individual differences.

Further reading:

Cunningham, H. (2009). The Invention of Childhood (p. 320). BBC Books.

Griffin, C. (1993). Representations of Youth. Polity Press.

Lesko, N. (2012). Act Your Age! The Cultural Construction of Adolescence. ` (Second Edition). Oxford: Routledge.

Lesko, N., & Talburt, S. (2012). A History of the Present Youth Studies. In N. Lesko & S. Talburt (Eds.), Key Words in Youth Studies. Routledge.

Reisinger, A. J. (2012). Histories. In N. Lesko & S. Talburt (Eds.), Key Words in Youth Studies. Routledge.

Scott, S. J. and S. (1999). Risk anxiety and the social construction of childhood. In Deborah Lupton (Ed.), Risk and Sociocultural Theory (pp. 86–108). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Seaton, E. (2012). Biology/Nature. In N. Lesko & S. Talburt (Eds.), Key Words in Youth Studies. Routledge.

Zelizer, V. A. (1994). Pricing the Priceless Child: The Changing Social Value of Children. Princeton University Press.

1468-0491/asset/society_affiliation_image.gif?v=1&s=859caf337f44d9bf73120debe8a7ad67751a0209)

1756-2589/asset/NCFR_RGB_small_file.jpg?v=1&s=0570a4c814cd63cfaec3c1e57a93f3eed5886c15)