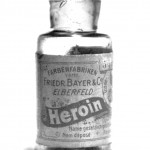

Nation’s Latest Drug Scare, Heroin is Back

The death of Philip Seymour Hoffman triggered a national awareness that heroin had cycled back as a prominent drug in the United States. His death brought forth questions that challenged many people’s notions of a drug user—poor and unsuccessful. Many people asked how a person who had so much could get addicted to heroin. The reality is that Hoffman was one of many people throughout the United States using heroin. According to the National Survey on Drug Abuse and Health, 335,000 people used heroin in 2012 up from 239,000 people in 2010.

The popularity or usage of rates of a drug have long been cyclical, as the supply of one drug is restricted people turn to another drug. Many scholars suggest that the popularity of heroin in the past few years is a combination of law enforcement crack downs on access to prescription pain killers and the flooding of the drug market with heroin due to record growth in Afghanistan. For instance, one report suggests that the introduction of a tamper-resistant formulation of OxyContin is leading to increases in heroin use. Research conducted by Cicero et al. (2012) indicates that the use of OxyContin through inhalation or intravenous administration has dropped since the new formulation of OxyContin was released, and they found many painkiller users are now turning to heroin. Their research coincides with an increase in heroin-related emergency department visits, substance abuse treatment admissions, and overdose deaths seen since 2010 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). Research on the transition from prescription pain killers to heroin following the reformulation of OxyContin cite the lower cost, increased availability, tolerance and seeking a more potent high as primary reasons for transitioning to heroin (Cicero et al., 2012). This notion is generally supported by patterns in prescription painkiller use for nonmedical reasons has dropped from 566,000 in 2010 to 358,000 in 2012.

Philippe Bourgois and Jeffrey Schonberg’s (2009) Righteous Dopefiend provides insight into the everyday struggle of heroin users to find their next fix and manage their lives while often living on the street. The study shows the consequences of heroin use as individuals put themselves at risk of serious health by sharing or using old needles, often leading to infections. Righteous Dopefiend also warns of the dangers of avoiding law enforcement detection, or else the threat of jail and the loss of their belongings. The focus by law enforcement on heroin users is tied to notions of keeping public space free from drugs, but also the idea that heroin users are regularly involved in acquisitive crime. A study in the United Kingdom found that over half of individuals arrested for property crime test positive for drugs (Boreham et al., 2007). Further, a study of juvenile heroin users found that 75 percent of the sample had committed a property crime to support their drug habit. While these findings fall short of causal relationships, these correlations are used to justify the criminal justice system’s harsh response to drug users. Combined with an often moralistic outrage towards drug use and we have a system that partially explains why the United States has been engaged in the war on drugs over the past 30 years.

Numerous scholars have opposed the United States’ harsh response to drug use and have advocated for the adoption of a medical model to respond to drug issues (see Bourgois & Schonberg, 2009). The medical model advocates for a more humanitarian approach to drug users focused on getting them better, and recognizing that addiction cannot be overcome through jail time. The medical model, as it applies to heroin users, also has the ability to reduce the risk of HIV, infections, overdoses, and other dangers of self-administered drug use. Many cities have set-up free needle exchanges in order to reduce the associated health risks of heroin use. Finally, this approach to heroin use will also have an impact on the criminal justice system by drastically reducing the number of individuals arrested for drug use or buying drugs for personal use.

References

Boreham, R., Cronberg, A., Dollin, L., & Pudney, S. (2007). The Arrestee Survey 2003-2006. London: Home Office.

Bourgois, P., & Schonberg, J. (2009). Righteous Dopefiend. University of California Press.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2012). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER (database). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Cicero, T.J., Ellis, M.S., & Surratt, H.L. (2012). Effect of abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin. The New England Journal of Medicine, 367, 187-189.

1475-682X/asset/akdkey.jpg?v=1&s=eef6c6a27a6d15977bc8f9cc0c7bc7fbe54a32de)