'Real' Men Don't Rape, and Other 'Sexy' Language Dilemmas

Following on from a report from the White House on student sexual assault, the Obama administration has recently released an anti-rape PSA to launch the ‘1 Is 2 Many’ campaign to address the issue of sexual assault and rape. If you haven’t already watched it then do: it has a refreshing and positive rhetoric, placing the focus on the perpetrator and not the victim. “If I saw it happening I would help her, not blame her”, Daniel Craig states. It follows an argument that is entirely reasonable but often forgotten, that it is more effective to teach people not to rape than it is to teach people not to get raped.

I like this advert for a number of reasons. It is clear and concise, moving and inspiring without being patronising, and doesn’t rely on ‘misery porn’ or fear to get its point across. It has a sense of hope and optimism, a “we can do this!” attitude. It is encouraging rather than threatening and manages to discuss rape whilst being approachable. I say all this because I don’t want to fall into the sociological trap of jumping straight into criticism without saying positive things, or to belittle how progressive this perspective is. This advert is a significant improvement on anti-rape campaigns that blame the victim, and I hope for more. However, there are overarching themes that this video throws up that I have to acknowledge, because despite liking this advert, it still has discursive effects and impact beyond simply preventing rape.

In the part of London I live in there was a similar campaign seeking to tackle rape by speaking directly to men. Like the video, it reminds men that sex without consent is rape and that “Real men know the difference”. This mode of persuasion is highly problematic, because it uses aspiration to a masculine ideal as a motivation for men not raping. Rather than seeking to subvert this masculine discourse they simply recast it against rape. The video also draws on this kind of chivalry: “It’s happening to our sisters, wives, mothers, daughters”, implying that men should be protecting and caring about women they care about.

Given that statistics on rape suggest that somewhere between 50 and 90 per cent of reported rapes are committed by someone known to the victim, this argument becomes flawed. What happens for those “sisters, wives, mothers, daughters” who are raped by their husbands, brothers, boyfriends, fathers? This rhetoric reaffirms the man as ‘protector’, and again assumes that rape primarily occurs between strangers. It also implies that a rapist might be persuaded not to at the thought that it might be one of ‘their women’. Similarly, it silences the experiences of male rape survivors and reinforces an idea that men must and should be able to protect themselves and others.

Rape is fundamentally about power; it is a “deliberate act on the part of the rapist, a violation of another person committed solely because the rapist wanted to rape”. Whilst a ‘White Knight’ call to arms may attempt rape prevention on an individual level, it will not dismantle societal structures of gender, domination and power, and where these perceptions of rape and rapists have an enduring effect. It does not tackle rape culture or conviction rates, or the growing issue of rape on college campuses and universities, or increased sexualisation and objectification of women in the media, or the multitudes of contributing factors to rape culture and sexual violence. If you attempt to appeal to men by asserting that real, strong, protective, good men don’t rape, you are attempting to prevent an act that is often regarded as the epitome of male domination over women, by reasserting patriarchal norms.

A second issue with these kinds of adverts is their reliance on what is called ‘grey rape’, asserting cultural tropes that may be damaging to those they intend to protect. It is clear that a message of ‘no means no’ and encouraging consent is important, but they often take an empathetic tone that seems to say, “Hey, I get it, knowing the difference is tricky sometimes”. This is good in that it challenges the notion that rape is something that happens between strangers in dark alleyways, but still creates a dilemma – how do you promote the idea that anyone could be a rapist without allowing the existence of a grey area between consent and non-consent, and therefore promoting rape culture?

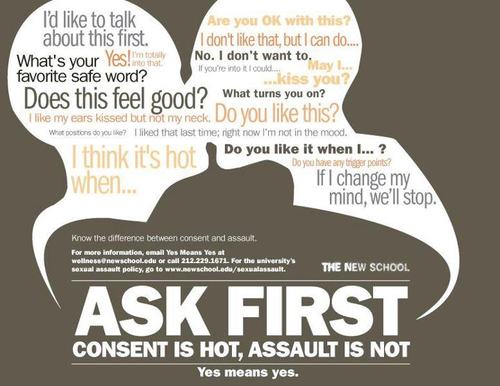

One way this can be broached is by teaching young men (and women) thatconsent is sexy, and to hold out for “enthusiastic consent”, rather than just knowing that no means no. This promotes sex-positivity as a force against rape, rather than reinforcing patriarchal norms. The phrase “enthusiastic consent” brings a smirk in feminist or academic circles, but in some areas it is entirely a joke, and doesn’t actually translate into the lived experiences of men and women negotiating their sex lives. A recent episode in the TV series New Girl for example, or this anti-rape PSA, makes a joke about consent. The message is clear; repeatedly asking someone his or her consent at every stage of the process is awkward, funny, and entirely unsexy.

What is so often missed from ‘consent is sexy’ discussions is that language we have to discuss sex often isn’t imbued with a sense of empowerment. I keep being reminded of Holland and colleagues’ seminal study: The ‘Male in the Head’. They argue that because the language available to discuss sexual practices is either scientific (penis, vagina, intercourse) or crude (cock, cunt, fuck), young people and young women in particular have difficulty expressing their wants and desires. Saying ‘Consent is sexy’ is an excellent message but the language of consent often doesn’t lend itself to sex, and is far cry from the “enthusiastic consent” seen in film and pornography. What this research shows is a deeper understanding for the real and lived sexual politics of young people, without removing it from the context of power and gender. It isn’t about reasserting gender power differences or blaming the victim, and it doesn’t have to encourage a belief in the ‘grey area’ between consent and non-consent to appreciate that sex is more complicated than just the difference between yes and no.

Thank you also to @notarapevictim for sharing her story with me, and inspiring some aspects of this post.

Additional References

1530-2415/asset/SPSSI_logo_small.jpg?v=1&s=703d32c0889a30426e5264b94ce9ad387c90c2e0)

I’m not sure a rapist would discern the masculine discourse set against rape in the advert but I’m sure it makes it far easier to grasp and I guess rapists would understand that because the nature of the violence is power. Power, masculinity etc are things therefore a rapist could relate to? Sexy consent is fucking aace, why have I never heard of this term- oh right, I’m not an academic.