New Look at Gentrification

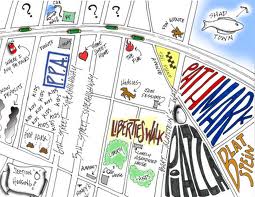

On a recent visit home to Philadelphia, I was astonished to see how drastically some parts of the city have changed. I am especially amazed by Northern Liberties, a chic couple of blocks with hip bars, show venues, outdoor markets, along with a few art galleries and unique shops. I remember nine or ten years ago I used to go to a little music venue close by called the Fire. At that time, the space that is now known as Northern Liberties was made up of empty lots and old buildings in disrepair. As a sociologist interested in urban issues and specifically, gentrification, I am continually trying to understand how neighborhoods and cities transform into attractive and sought-after spaces. As my friend and I were driving through “NoLibs” that day, talking about the coming of the Brooklyn Flea (a popular flea market originated in Brooklyn) to the neighborhood later that weekend, we asked ourselves, how did this happen?

Japonica Brown-Saracino’s (2010) in-depth reader The Gentrification Debates, explores the explanations, consequences, and experiences of gentrification. The contributors range from Sharon Zukin and Neil Smith, academic pioneers on the topic, to Richard Florida who coined the term the “creative class”. Sharon Zukin uses the concept of authenticity to understand gentrification. Authenticity is understood as the thing/feature/person/etc. that makes a place unique: where do you go to experience Mardi Gras? The answer has to be New Orleans – Mardi Gras is New Orleans and vice versa. Zukin (2010) believes consumption and consumerism is the means by which individuals create authenticity, which has the power to turn Brooklyn or Harlem or the Lower East Side into a hip/cool place to be [you have to go there if you want the real thing]. Richard Florida’s creative class thesis empowers cities to utilize authenticity as marketing. Florida thinks cities should intentionally attract middle-class, urban intellectuals in order for cities to prosper: money = growth, attract the middle-class via trends in arts, green living, etc. and in turn a city will grow.

In these accounts and quandaries over how and why gentrification occurs and whether it’s for the best or not, the commonality is a focus on individuals. Though it is individuals who help produce and sustain a neighborhood (via consumption and social interest), there are decisions far beyond the purview of the individual that make gentrification possible. Decisions such as how to zone a parcel of land, the selling of state/city land, eminent domain, and closed-door conversations with developers, are all necessary if physical space is intended to change (see Fleischmann 1989 and Rose 2004). Think of it this way – all cities are built on land, all land is designated for a specific purpose (agriculture, commercial, industrial, residential); if a piece of land changes (physically, socially, etc.) there is a political mechanism which has deemed that change acceptable.

In cities like Philadelphia and beyond there are noticeable changes to the landscapes. The conversations about gentrification seem to center around stories about tension among residents. Our media’s fascination with defining and understanding the individuals responsible for gentrification-whether they be hipsters, millennials, or yuppies- attest to how those in non-academic circles are also looking at gentrification through the lens of individuals. My question is – what are the political decisions allowing for neighborhood change? The commonplace debate of gentrification places too much responsibility on the interests and demands of individuals and too little attention on political will. When asking the familiar question, “how did that happen?” it is important to look pass what is happening on the street, and find ways to examine the political decisions involved in change.

Suggested Reading:

Brown-Saracino, Japonica. 2010. The Gentrification Debates. New York: Routledge.

Zukin, Sharon. 2008. “Consuming Authenticity: From outposts of difference to means of exclusion.” Cultural Studies 22(5): 724-748.

1467-7660/asset/DECH_right.gif?v=1&s=a8dee74c7ae152de95ab4f33ecaa1a00526b2bd2)

1756-2589/asset/NCFR_RGB_small_file.jpg?v=1&s=0570a4c814cd63cfaec3c1e57a93f3eed5886c15)